Questions Posted in the last picture.

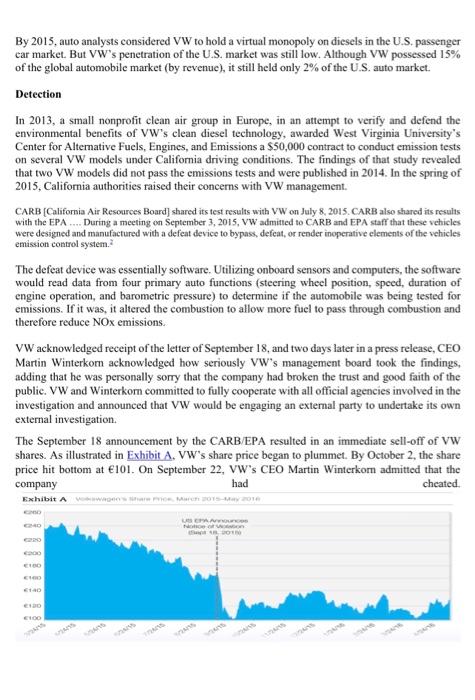

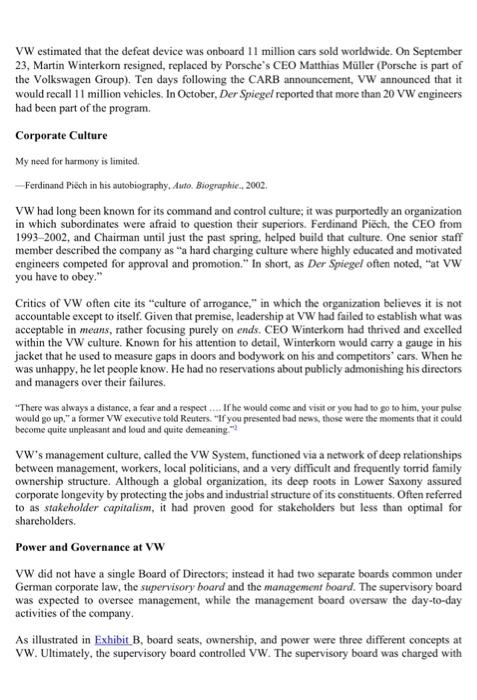

Case Study 1 Volkswagen's Defeat Devices and Stakeholder Control I1 Today, EPA is issuing a notice of violation (NOV) of the Clean Air Act (CAA) to Volkswagen AG, Audi AG, and Volkswagen Group of America, Inc. (collectively referred to as Volkswagen). The NOV alleges that four cylinder Volkswagen and Audi diesel cars from model years 2009-2015 include softwate that circumvents EPA cmissions standards for certain air pollutants. -U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Newsroom, 9/18/2015. The discovery of Volkswagen's intentional deception on the NOx (nitrogen oxide) emissions of its diesel engines in September 2015 resulted in the loss of 30% of the company's market value. In the months that followed, VW found itself under attack from every possible interestgovernment regulators, consumer interest groups, customers, dealers, and its own stockholders. It faced $18 billion in potential financial penalties and possibly irreparable damage to its global reputation. How did VW's leadership allow this to happen? Volkswagen and Diesel Volkswagen (VW) is a German automobile manufacturer headquartered in Wolfsburg. Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded by a labor group in 1936, the company had enjoyed a rich history of challenges and successes. By 2015 Volkswagen Group was a multinational holding company of car and truck products including VW, SEAT, Audi, Lamborghini, Porsche, Benticy, Bugatti, Scania, and Skoda. VW had become the second largest (to Toyota of Japan) automobile manufacturer in the world. But VW struggled to penetrate the North American market. Having been largely absent since the 1960s, VW made a major push to reenter the U.S. in 2007. When Martin Winterkorn was appointed CEO in 2007, he had given specific instructions: triple sales in the U.S. to 800,000 cars by 2018 . His strategy was diesel. Diesel Engines Diesel was more efficient than gasoline, converting heat into more energy than gasoline. Diesels ran at higher compression, generating more torque, but operated in a relatively narrow power band that worked best when operated for a longer period of time. Diesel engine exhaust had lower carbon monoxide production, but higher particulate and nitrogen oxides emissions. And U.S. emissions restrictions on passenger automobiles were the most stringent in the world. Califomia, an enormous market, was the most stringent of all. There were two basic technologies used to reduce NOx emissions, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and the lean NOx trap (LNT). The first was by far the most eftective, but VW had concluded it was too expensive and added too much weight. The second method decreased fuel combustion efficiency and lowered mileage and performance. It was cheaper and lighter, but less effective, than SCR. It was this technology that VW employed in the vehicles equipped with defeat devices. By 2015, auto analysts considered VW to hold a virtual monopoly on diesels in the U.S. passenger ear market. But VW's penetration of the U.S. market was still low. Although VW possessed 15% of the global automobile market (by revenue), it still held only 2% of the U.S. auto market. Detection In 2013, a small nonprofit clean air group in Europe, in an attempt to verify and defend the environmental benefits of VW's clean diesel technology, awarded West Virginia University's Center for Alternative Fuels, Engines, and Emissions a $50,000 contract to conduct emission tests on several VW models under California driving conditions. The findings of that study revealed that two VW models did not pass the emissions tests and were published in 2014. In the spring of 2015, California authorities raised their concerns with VW management. CARB [California Air Resources Board] shared its test results with VW on July 8, 2015. CARB also shared its results with the EPA ... During a meeting on September 3, 2015, VW admitted to CARB and EPA staff that these vehicles were designed and manufactured with a defeat device to bypass, defeat, or render inoperative elements of the vehicles emission control system. 2 The defeat device was essentially software. Utilizing onboard sensors and computers, the software would read data from four primary auto functions (steering wheel position, speed, duration of engine operation, and barometric pressure) to determine if the automobile was being tested for emissions. If it was, it altered the combustion to allow more fuel to pass through combustion and therefore reduce NOx emissions. VW acknowledged receipt of the letter of September 18, and two days later in a press release, CEO Martin Winterkorn acknowledged how seriously VW's management board took the findings, adding that he was personally sorry that the company had broken the trust and good faith of the public. VW and Winterkom committed to fully cooperate with all official agencies involved in the investigation and announced that VW would be engaging an external party to undertake its own external investigation. The September 18 announcement by the CARB/EPA resulted in an immediate sell-off of VW shares. As illustrated in Exhibit A. VW's share price began to plummet. By October 2, the share price hit bottom at 101. On September 22, VW's CEO Martin Winterkorn admitted that the company had cheated VW estimated that the defeat device was onboard 11 million cars sold worldwide. On September 23, Martin Winterkorn resigned, replaced by Porsche's CEO Matthias Mller (Porsche is part of the Volkswagen Group). Ten days following the CARB announcement, VW announced that it would recall 11 million vehicles. In October, Der Spiegel reported that more than 20VW engineers had been part of the program. Corporate Culture My need for harmony is limited. -Ferdinand Piech in bis autobiography, Auta. Biographie,, 2002. VW had long been known for its command and control culture, it was purportedly an organization in which subordinates were afraid to question their superiors. Fendinand Piech, the CEO from 1993-2002, and Chairman until just the past spring, helped build that culture. One senior staff member described the company as "a hard charging culture where highly educated and motivated engineers competed for approval and promotion." In short, as Der Spiegel often noted, "at VW you have to obey." Critics of VW often cite its "culture of arrogance," in which the organization believes it is not accountable except to itself. Given that premise, leadership at VW had failed to establish what was acceptable in means, rather focusing purely on ends. CEO Winterkom had thrived and excelled within the VW culture. Known for his attention to detail, Winterkorn would carry a gauge in his jacket that he used to measure gaps in doors and bodywork on his and competitors' cars. When he was unhappy, he let people know. He had no reservations about publicly admonishing his directors and managers over their failures. "There was always a distanoc, a fear and a respect.... If he would come and visit or you had to go to him, your pulse would go up," a former VW executive told Reuters. "If you presented bad newx, those were the moments that it could become quite unpleasant and lood and quite demeaning."-2 VW's management culture, called the VW System, functioned via a network of deep relationships between management, workers, local politicians, and a very difficult and frequently torrid family ownership structure. Although a global organization, its deep roots in Lower Saxony assured corporate longevity by protecting the jobs and industrial structure of its constituents. Often referred to as stakeholder capitalism, it had proven good for stakeholders but less than optimal for shareholders. Power and Governance at VW VW did not have a single Board of Directors; instead it had two separate boards common under German corporate law, the supervisory board and the management board. The supervisory board was expected to oversee management, while the management board oversaw the day-to-day activities of the company. As illustrated in Exhibit B, board seats, ownership, and power were three different concepts at VW. Ultimately, the supervisory board controlled VW. The supervisory board was charged with the oversight of the management board, the entity responsible for the execution of the business. The supervisory board was not controlled by any one entity, but rather was a compromise of labor and other stakeholders. Half of the supervisory board seats were held by representatives of workers, the works council. The head of IG Metall, a large German labor union, held a board seat and served as interim chairman at the time of the crisis. The other half of the supervisory board, representing shareholders' interests, also held 10 board seats. This group was dominated by three entities: (1) the Porsche and Piecch families, holding four board seats through their ownership of Porsche Automobil Holdings; (2) the government of Lower Saxony, holding two seats; and (3) Qatar Investment Holdings, holding two seats. The remaining two seats were held by outsiders, although these "outsiders" typically had strong relationships with the Porsche and Piecch families. The ownership of the company was similar, but not identical to, the board seat structure. The Porsche and Pich families owned 32% of the company, Lower Saxony 13%, Qatar 16\%, and the remaining 40% was held by outside investors through the free floating shares (traded on exchanges). But the ownership of shares did not translate directly into votes. The Porsche and Pich families held 51% of the votes in the company. Together with Lower Saxony's 20.0% of the votes and Qatar lnvestment Holdings' 17.0%, only 12% of the votes were held by outsiders. The Supervisory Board had four committees: audit, nomination, mediation, and presidium. It was the presiditm, the executive committee often referred to as the inner circle, that held the power. Its official charge was to "discuss and prepare decisions to be made by the full board, and to deal with contractual matters conceming the company's senior managers." 4 The presidium set the agenda for each Board meeting. At the time, the presidium had five members: (1) the board representative of IG Metall union; (2) chairman of VW's works council representing employees; (3) the vice chairman of the works council; (4) Wolfgang Porsche; and (5) the prime minister of the state of Lower Saxony. VW's corporate governance employed a common control device in Europe, the pyramid structure. Pyramid structures involve an entity (such as a family or a company) to control a corporation that, in turn, holds a controlling stake in another company. VW, at the time of the crisis, was effectively controlled by three men: Ferdinand Piech, his cousin Wolfgang Porsche, and Martin Winterkorn. Although Winterkorn was now gone, the new CEO. Matthis Meller, was a close associate of Pich. (The power of family at VW was very strong. Ursula Pich, a supervisory board member, had first been a kindergarten teacher, then Pich family governess, then Ferdinand Pich's fourth wife.) The Pich and Porsche families had an official agreement to unite their voting power. VW'S 2016 Mixed Message On January 4, 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a civil complaint against VW alleging the illegal installation of emissions defeat devices and importing vehicles into the U.S. violating the Clean Air Act. VW's response was to refuse to provide any communications among its executives to legal authorities in the U.S. on the basis of corporate privacy protection under German law. Germany had some of the most stringent legal protections on personal information in the world, particularly as provided to entities outside the EU. Ten days later, during VW's new CEO's first visit to the U.S., Matthis Meller seemed to backpedal on VW's admission of guilt. Frankly spoken, it was a technical problem. We made a defoult, we had a ... not the right interpretation of the American law. And we had some targets for our technical engineers, and they solved this problem and reached targets with some software solutions, which haven't been compatible to the American law. That is the thing. And the other question you mentioned-it was an cthical problem? I cannot understand why you say that. -Matthis Meller, CEO Volkswagen, National Public Radio Intervicw, January 11, 2016. The remarks ignited an overnight firestorm in the press. The following day Meller met with NPR once again in an attempt to clarify his comments. Unfortunately, it only seemed to make matters worse. We're doing our utmost. We have worked night and day to find solutions. Not only technical solutions. It's a lot of work for the lawyers and also for the press department. Although VW admitted it did indeed commit illegal acts in the U.S. (technically by lying to government regulators, not for installing the devices), the company noted that the device "is not a forbidden defeat device" under European rules. Although critics of all kinds were impatient with VW to disclose the results of its internal investigations, VW's leadership continued to argue that it was obligated by German corporate law to inform its shareholders first, and that could not happen prior to the April 2016 shareholder meeting. Changing Story The responsibility of leadership to divulge significant risks to a publicly traded company's shareholders in a timely manner was clear in both Germany and the United States. VW now reported that CEO Winterkorn was sent memos noting the issue more than a year before the issue arose publicly. VW argued that it was not known if Winterkorn had read them, explaining that he "might not have noticed them among his heavy weekend reading." Many insiders argued that VW's leadership did not understand that the defeat devices actually broke U.S. law, and believed that resolution would be achieved relatively easily and quickly with U.S. regulators. In a March 2 press release, VW responded to investor lawsuits and explained its reasoning: 5 Volkswagen considers the German shareholder lawsuits to be without merit, since any ad hoc disclosure obligation requires that the persons responsible for the fulfillment of this obligation obtain knowledge of facts relevant for the stock price and can assess the economic effects of those facts. With respect to the diesel matter, stock price relevance occurred only as of 18 September 2015 when the violation of U.S. environmental regulations was announced. Until then, there were no indications whatsoever of information with relevance for the stock price, since up until that point in time it was expected that a manageable number of vehicles (approx. 500,000) would be affected by the diesel matter and that fines in a two-digit or lower three-digit million amount would be imposed, as had been the case in the past in the U.S. in comparable cases involving passenger vehicles. Additionally, to the best knowledge, the diesel matter appeared to be an issue that could be contained by measures that were common in such cases, including effective technical solutions, and, thus, appeared to be neutral with regard to the Company's stock price. This was followed by a 113-page interim report from its own ongoing internal investigation, in which VW noted that it had been surprised by the issue being taken public by U.S. regulators. The company had assumed that continuing negotiations would follow the September findings, privately, to reach a resolution. In the past, even in the case of so-called defeat device infringements, a settlement was reached with other car-makers involving a manageable fine without the breach being made public. The now ex-CEO of VW, Martin Winterkorn, had opened the company's 2014 annual report to stakeholders with the corporate vision, a vision that now sounded increasingly hollow. Our pursuit of innovation and perfection and our responsible approach will help to make us the world's leading automaker by 2018 -both economically and ecologically. -Prof. Dr. Martin Winterkorn, Chairman of the Board of Management of Volkswagen Aktiengesellshaft. Mini-Case Questions 1. Describe the Volkswagen's (VW) corporate governance structure. 2. Have the goals of corporate governance been properly served by Volkswagen (VW)? Describe your thoughts. 3. Describe the various stakeholders and their individual interests in Volkswagen (VW). Whose interest dominated in the decision to pursue the defeat device strategy? 4. Does good governance exist in Volkswagen (VW)? If not, describe in which perspective it is lagging behind. What would you recommend that Volkswagen (VW) could do to improve its good governance? Case Study 1 Volkswagen's Defeat Devices and Stakeholder Control I1 Today, EPA is issuing a notice of violation (NOV) of the Clean Air Act (CAA) to Volkswagen AG, Audi AG, and Volkswagen Group of America, Inc. (collectively referred to as Volkswagen). The NOV alleges that four cylinder Volkswagen and Audi diesel cars from model years 2009-2015 include softwate that circumvents EPA cmissions standards for certain air pollutants. -U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Newsroom, 9/18/2015. The discovery of Volkswagen's intentional deception on the NOx (nitrogen oxide) emissions of its diesel engines in September 2015 resulted in the loss of 30% of the company's market value. In the months that followed, VW found itself under attack from every possible interestgovernment regulators, consumer interest groups, customers, dealers, and its own stockholders. It faced $18 billion in potential financial penalties and possibly irreparable damage to its global reputation. How did VW's leadership allow this to happen? Volkswagen and Diesel Volkswagen (VW) is a German automobile manufacturer headquartered in Wolfsburg. Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded by a labor group in 1936, the company had enjoyed a rich history of challenges and successes. By 2015 Volkswagen Group was a multinational holding company of car and truck products including VW, SEAT, Audi, Lamborghini, Porsche, Benticy, Bugatti, Scania, and Skoda. VW had become the second largest (to Toyota of Japan) automobile manufacturer in the world. But VW struggled to penetrate the North American market. Having been largely absent since the 1960s, VW made a major push to reenter the U.S. in 2007. When Martin Winterkorn was appointed CEO in 2007, he had given specific instructions: triple sales in the U.S. to 800,000 cars by 2018 . His strategy was diesel. Diesel Engines Diesel was more efficient than gasoline, converting heat into more energy than gasoline. Diesels ran at higher compression, generating more torque, but operated in a relatively narrow power band that worked best when operated for a longer period of time. Diesel engine exhaust had lower carbon monoxide production, but higher particulate and nitrogen oxides emissions. And U.S. emissions restrictions on passenger automobiles were the most stringent in the world. Califomia, an enormous market, was the most stringent of all. There were two basic technologies used to reduce NOx emissions, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and the lean NOx trap (LNT). The first was by far the most eftective, but VW had concluded it was too expensive and added too much weight. The second method decreased fuel combustion efficiency and lowered mileage and performance. It was cheaper and lighter, but less effective, than SCR. It was this technology that VW employed in the vehicles equipped with defeat devices. By 2015, auto analysts considered VW to hold a virtual monopoly on diesels in the U.S. passenger ear market. But VW's penetration of the U.S. market was still low. Although VW possessed 15% of the global automobile market (by revenue), it still held only 2% of the U.S. auto market. Detection In 2013, a small nonprofit clean air group in Europe, in an attempt to verify and defend the environmental benefits of VW's clean diesel technology, awarded West Virginia University's Center for Alternative Fuels, Engines, and Emissions a $50,000 contract to conduct emission tests on several VW models under California driving conditions. The findings of that study revealed that two VW models did not pass the emissions tests and were published in 2014. In the spring of 2015, California authorities raised their concerns with VW management. CARB [California Air Resources Board] shared its test results with VW on July 8, 2015. CARB also shared its results with the EPA ... During a meeting on September 3, 2015, VW admitted to CARB and EPA staff that these vehicles were designed and manufactured with a defeat device to bypass, defeat, or render inoperative elements of the vehicles emission control system. 2 The defeat device was essentially software. Utilizing onboard sensors and computers, the software would read data from four primary auto functions (steering wheel position, speed, duration of engine operation, and barometric pressure) to determine if the automobile was being tested for emissions. If it was, it altered the combustion to allow more fuel to pass through combustion and therefore reduce NOx emissions. VW acknowledged receipt of the letter of September 18, and two days later in a press release, CEO Martin Winterkorn acknowledged how seriously VW's management board took the findings, adding that he was personally sorry that the company had broken the trust and good faith of the public. VW and Winterkom committed to fully cooperate with all official agencies involved in the investigation and announced that VW would be engaging an external party to undertake its own external investigation. The September 18 announcement by the CARB/EPA resulted in an immediate sell-off of VW shares. As illustrated in Exhibit A. VW's share price began to plummet. By October 2, the share price hit bottom at 101. On September 22, VW's CEO Martin Winterkorn admitted that the company had cheated VW estimated that the defeat device was onboard 11 million cars sold worldwide. On September 23, Martin Winterkorn resigned, replaced by Porsche's CEO Matthias Mller (Porsche is part of the Volkswagen Group). Ten days following the CARB announcement, VW announced that it would recall 11 million vehicles. In October, Der Spiegel reported that more than 20VW engineers had been part of the program. Corporate Culture My need for harmony is limited. -Ferdinand Piech in bis autobiography, Auta. Biographie,, 2002. VW had long been known for its command and control culture, it was purportedly an organization in which subordinates were afraid to question their superiors. Fendinand Piech, the CEO from 1993-2002, and Chairman until just the past spring, helped build that culture. One senior staff member described the company as "a hard charging culture where highly educated and motivated engineers competed for approval and promotion." In short, as Der Spiegel often noted, "at VW you have to obey." Critics of VW often cite its "culture of arrogance," in which the organization believes it is not accountable except to itself. Given that premise, leadership at VW had failed to establish what was acceptable in means, rather focusing purely on ends. CEO Winterkom had thrived and excelled within the VW culture. Known for his attention to detail, Winterkorn would carry a gauge in his jacket that he used to measure gaps in doors and bodywork on his and competitors' cars. When he was unhappy, he let people know. He had no reservations about publicly admonishing his directors and managers over their failures. "There was always a distanoc, a fear and a respect.... If he would come and visit or you had to go to him, your pulse would go up," a former VW executive told Reuters. "If you presented bad newx, those were the moments that it could become quite unpleasant and lood and quite demeaning."-2 VW's management culture, called the VW System, functioned via a network of deep relationships between management, workers, local politicians, and a very difficult and frequently torrid family ownership structure. Although a global organization, its deep roots in Lower Saxony assured corporate longevity by protecting the jobs and industrial structure of its constituents. Often referred to as stakeholder capitalism, it had proven good for stakeholders but less than optimal for shareholders. Power and Governance at VW VW did not have a single Board of Directors; instead it had two separate boards common under German corporate law, the supervisory board and the management board. The supervisory board was expected to oversee management, while the management board oversaw the day-to-day activities of the company. As illustrated in Exhibit B, board seats, ownership, and power were three different concepts at VW. Ultimately, the supervisory board controlled VW. The supervisory board was charged with the oversight of the management board, the entity responsible for the execution of the business. The supervisory board was not controlled by any one entity, but rather was a compromise of labor and other stakeholders. Half of the supervisory board seats were held by representatives of workers, the works council. The head of IG Metall, a large German labor union, held a board seat and served as interim chairman at the time of the crisis. The other half of the supervisory board, representing shareholders' interests, also held 10 board seats. This group was dominated by three entities: (1) the Porsche and Piecch families, holding four board seats through their ownership of Porsche Automobil Holdings; (2) the government of Lower Saxony, holding two seats; and (3) Qatar Investment Holdings, holding two seats. The remaining two seats were held by outsiders, although these "outsiders" typically had strong relationships with the Porsche and Piecch families. The ownership of the company was similar, but not identical to, the board seat structure. The Porsche and Pich families owned 32% of the company, Lower Saxony 13%, Qatar 16\%, and the remaining 40% was held by outside investors through the free floating shares (traded on exchanges). But the ownership of shares did not translate directly into votes. The Porsche and Pich families held 51% of the votes in the company. Together with Lower Saxony's 20.0% of the votes and Qatar lnvestment Holdings' 17.0%, only 12% of the votes were held by outsiders. The Supervisory Board had four committees: audit, nomination, mediation, and presidium. It was the presiditm, the executive committee often referred to as the inner circle, that held the power. Its official charge was to "discuss and prepare decisions to be made by the full board, and to deal with contractual matters conceming the company's senior managers." 4 The presidium set the agenda for each Board meeting. At the time, the presidium had five members: (1) the board representative of IG Metall union; (2) chairman of VW's works council representing employees; (3) the vice chairman of the works council; (4) Wolfgang Porsche; and (5) the prime minister of the state of Lower Saxony. VW's corporate governance employed a common control device in Europe, the pyramid structure. Pyramid structures involve an entity (such as a family or a company) to control a corporation that, in turn, holds a controlling stake in another company. VW, at the time of the crisis, was effectively controlled by three men: Ferdinand Piech, his cousin Wolfgang Porsche, and Martin Winterkorn. Although Winterkorn was now gone, the new CEO. Matthis Meller, was a close associate of Pich. (The power of family at VW was very strong. Ursula Pich, a supervisory board member, had first been a kindergarten teacher, then Pich family governess, then Ferdinand Pich's fourth wife.) The Pich and Porsche families had an official agreement to unite their voting power. VW'S 2016 Mixed Message On January 4, 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a civil complaint against VW alleging the illegal installation of emissions defeat devices and importing vehicles into the U.S. violating the Clean Air Act. VW's response was to refuse to provide any communications among its executives to legal authorities in the U.S. on the basis of corporate privacy protection under German law. Germany had some of the most stringent legal protections on personal information in the world, particularly as provided to entities outside the EU. Ten days later, during VW's new CEO's first visit to the U.S., Matthis Meller seemed to backpedal on VW's admission of guilt. Frankly spoken, it was a technical problem. We made a defoult, we had a ... not the right interpretation of the American law. And we had some targets for our technical engineers, and they solved this problem and reached targets with some software solutions, which haven't been compatible to the American law. That is the thing. And the other question you mentioned-it was an cthical problem? I cannot understand why you say that. -Matthis Meller, CEO Volkswagen, National Public Radio Intervicw, January 11, 2016. The remarks ignited an overnight firestorm in the press. The following day Meller met with NPR once again in an attempt to clarify his comments. Unfortunately, it only seemed to make matters worse. We're doing our utmost. We have worked night and day to find solutions. Not only technical solutions. It's a lot of work for the lawyers and also for the press department. Although VW admitted it did indeed commit illegal acts in the U.S. (technically by lying to government regulators, not for installing the devices), the company noted that the device "is not a forbidden defeat device" under European rules. Although critics of all kinds were impatient with VW to disclose the results of its internal investigations, VW's leadership continued to argue that it was obligated by German corporate law to inform its shareholders first, and that could not happen prior to the April 2016 shareholder meeting. Changing Story The responsibility of leadership to divulge significant risks to a publicly traded company's shareholders in a timely manner was clear in both Germany and the United States. VW now reported that CEO Winterkorn was sent memos noting the issue more than a year before the issue arose publicly. VW argued that it was not known if Winterkorn had read them, explaining that he "might not have noticed them among his heavy weekend reading." Many insiders argued that VW's leadership did not understand that the defeat devices actually broke U.S. law, and believed that resolution would be achieved relatively easily and quickly with U.S. regulators. In a March 2 press release, VW responded to investor lawsuits and explained its reasoning: 5 Volkswagen considers the German shareholder lawsuits to be without merit, since any ad hoc disclosure obligation requires that the persons responsible for the fulfillment of this obligation obtain knowledge of facts relevant for the stock price and can assess the economic effects of those facts. With respect to the diesel matter, stock price relevance occurred only as of 18 September 2015 when the violation of U.S. environmental regulations was announced. Until then, there were no indications whatsoever of information with relevance for the stock price, since up until that point in time it was expected that a manageable number of vehicles (approx. 500,000) would be affected by the diesel matter and that fines in a two-digit or lower three-digit million amount would be imposed, as had been the case in the past in the U.S. in comparable cases involving passenger vehicles. Additionally, to the best knowledge, the diesel matter appeared to be an issue that could be contained by measures that were common in such cases, including effective technical solutions, and, thus, appeared to be neutral with regard to the Company's stock price. This was followed by a 113-page interim report from its own ongoing internal investigation, in which VW noted that it had been surprised by the issue being taken public by U.S. regulators. The company had assumed that continuing negotiations would follow the September findings, privately, to reach a resolution. In the past, even in the case of so-called defeat device infringements, a settlement was reached with other car-makers involving a manageable fine without the breach being made public. The now ex-CEO of VW, Martin Winterkorn, had opened the company's 2014 annual report to stakeholders with the corporate vision, a vision that now sounded increasingly hollow. Our pursuit of innovation and perfection and our responsible approach will help to make us the world's leading automaker by 2018 -both economically and ecologically. -Prof. Dr. Martin Winterkorn, Chairman of the Board of Management of Volkswagen Aktiengesellshaft. Mini-Case Questions 1. Describe the Volkswagen's (VW) corporate governance structure. 2. Have the goals of corporate governance been properly served by Volkswagen (VW)? Describe your thoughts. 3. Describe the various stakeholders and their individual interests in Volkswagen (VW). Whose interest dominated in the decision to pursue the defeat device strategy? 4. Does good governance exist in Volkswagen (VW)? If not, describe in which perspective it is lagging behind. What would you recommend that Volkswagen (VW) could do to improve its good governance

Questions Posted in the last picture.

Questions Posted in the last picture.