Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

read and summarize the above text and put it in a PowerPoint presentation form. 12 to 14 slides ***chegg doesn't support PowerPoint presentation documents hence

read and summarize the above text and put it in a PowerPoint presentation form. 12 to 14 slides

***chegg doesn't support PowerPoint presentation documents hence take screenshots or snapshots and post the images of the said work on here.

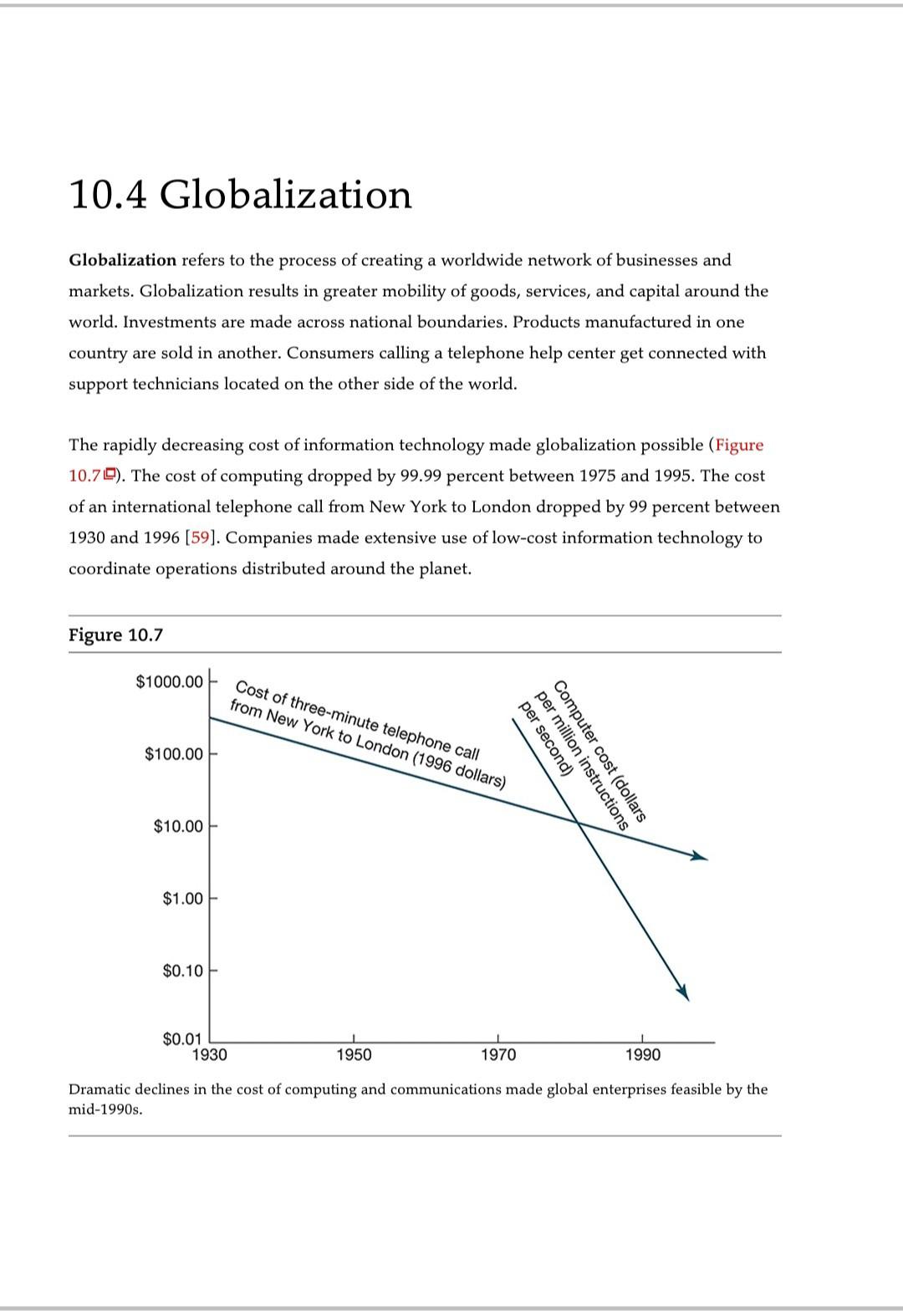

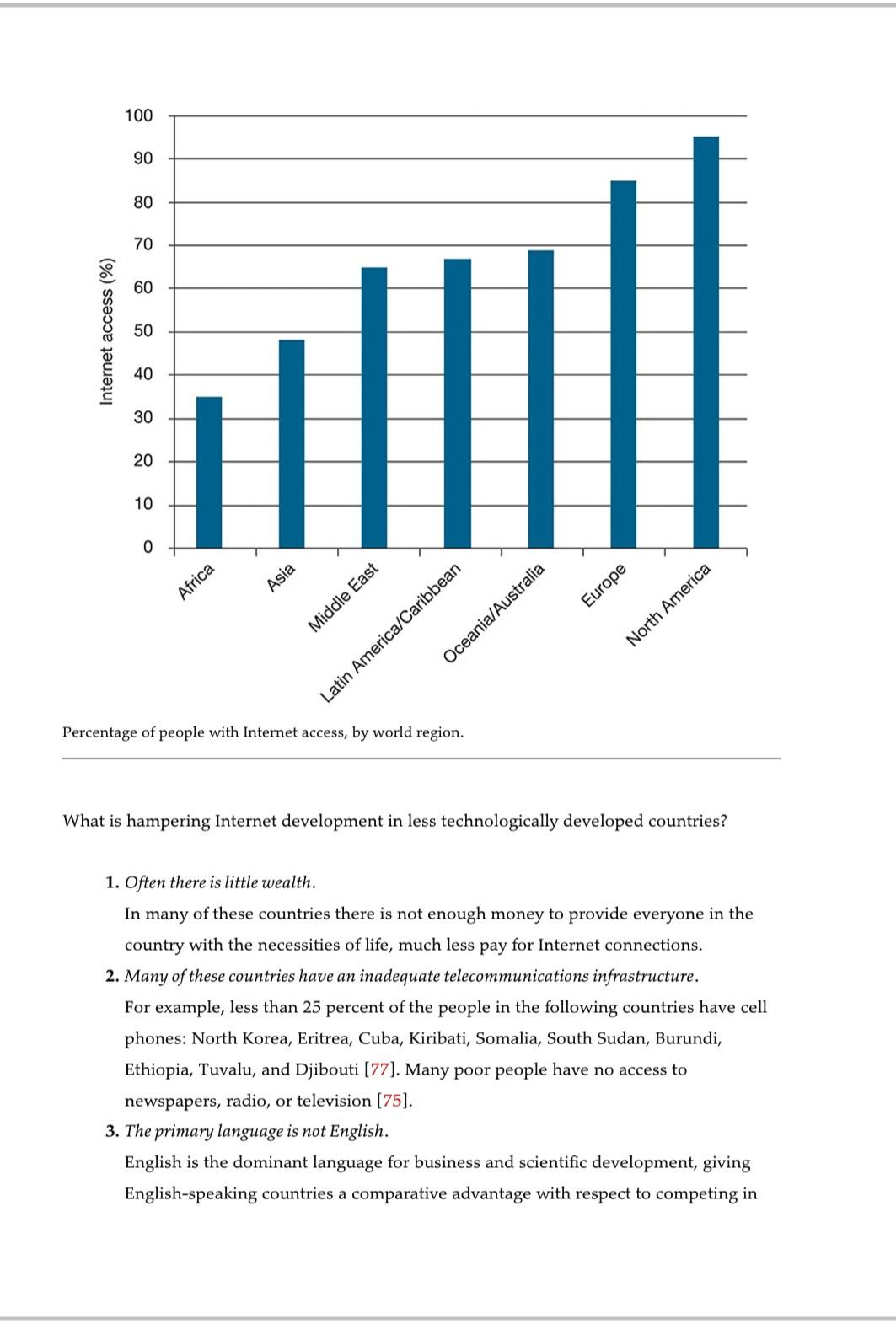

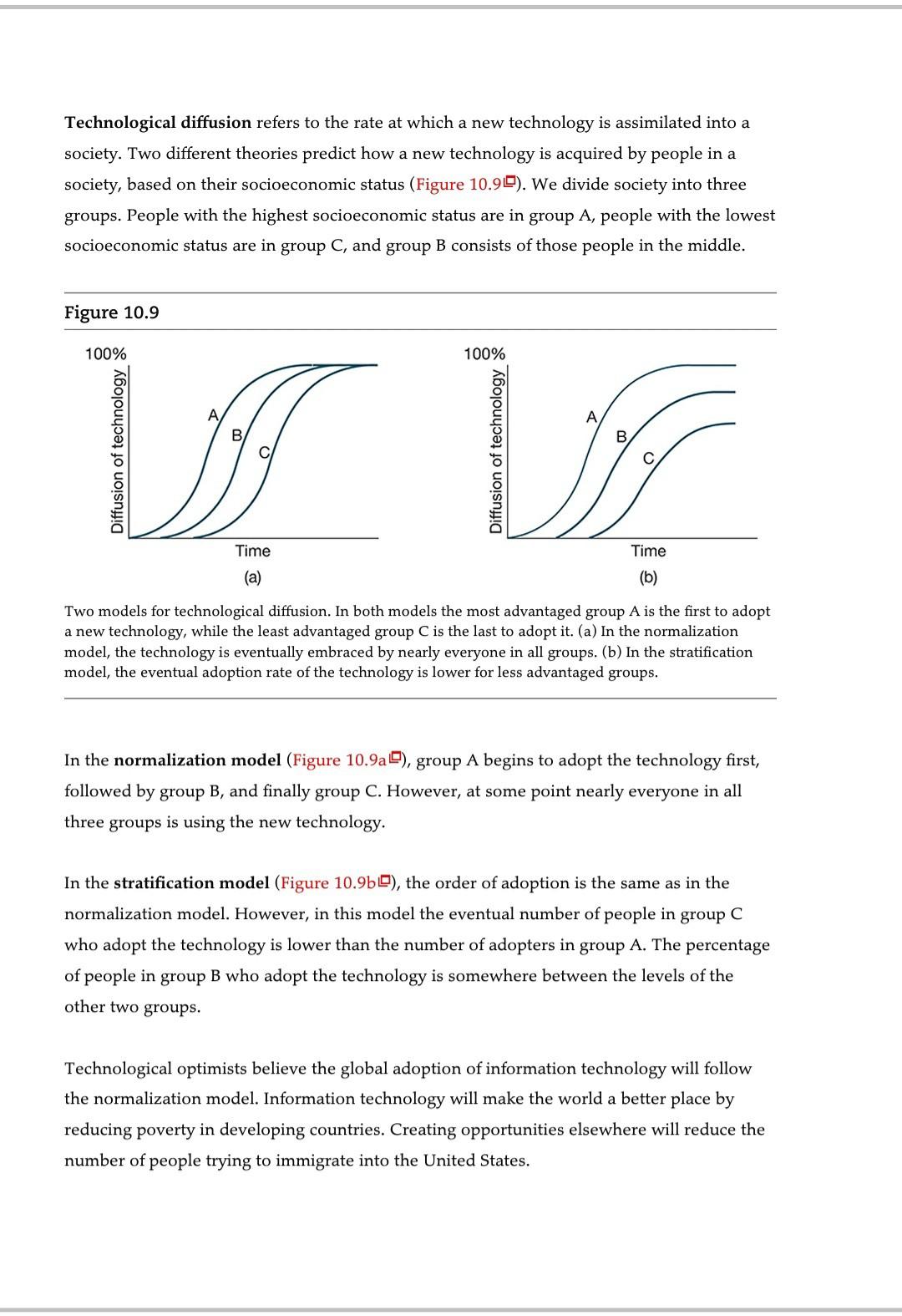

10.4 Globalization Globalization refers to the process of creating a worldwide network of businesses and markets. Globalization results in greater mobility of goods, services, and capital around the world. Investments are made across national boundaries. Products manufactured in one country are sold in another. Consumers calling a telephone help center get connected with support technicians located on the other side of the world. The rapidly decreasing cost of information technology made globalization possible (Figure 10.70). The cost of computing dropped by 99.99 percent between 1975 and 1995. The cost of an international telephone call from New York to London dropped by 99 percent between 1930 and 1996 (59). Companies made extensive use of low-cost information technology to coordinate operations distributed around the planet. Figure 10.7 $1000.00 Cost of three-minute telephone call from New York to London (1996 dollars) $100.00 per second) per million instructions Computer cost (dollars $10.00 $1.00 $0.10 $0.01 1930 1950 1970 1990 Dramatic declines in the cost of computing and communications made global enterprises feasible by the mid-1990s. 10.4.1 Arguments For Globalization Those who favor globalization seek the removal of trade barriers between nations. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) among Canada, the United States, and Mexico was a step toward globalization. The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an international body that devises rules for international trade and promotes the goal of free trade among nations. The WTO and other proponents of globalization support free trade with these arguments: 1. Free trade can increase everyone's standard of living. Every country has a comparative advantage at producing certain products and services, meaning it can produce them at a lower opportunity cost than any other country. Consumers get better prices when each area produces the goods or services it does best-corn in Kansas, automobiles in Ontario, semiconductors in Singapore, and so on-and then these products and services are bought and sold without trade barriers. When prices are lower, the real purchasing power of consumers is higher. Hence globalization increases everyone's standard of living. 2. People in poorer countries deserve jobs, too. When they gain employment, their prosperity increases. 3. Every example in the past century of a poor country becoming more prosperous has been the result of that country producing goods for the world market rather than striving for self- sufficiency [60]. Contrast the remarkable success story that is South Korea with the economic basket case that is North Korea. 4. Creating jobs around the world reduces unrest and leads to more stability. Countries with interdependent economies are less likely to go to war with each other. 10.4.2 Arguments Against Globalization Ralph Nader, American trade unions, the European farm lobby, and organizations such as Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, and Oxfam oppose globalization. They give these reasons why globalization is a bad trend: 1. The United States and other governments should not be subordinate to the WTO. The WTO makes the rules for globalization, but nobody elected it. It makes its decisions behind closed doors. Every member country, from the United States to the tiniest dictatorship, has one vote in the WTO. 2. American workers should not be forced to compete with foreign workers who do not receive decent pay and working conditions. The WTO does not require member countries to protect the rights of their workers. It has not banned child labor. Authoritarian regimes such as the People's Republic of China are allowed to participate in the WTO even though they do not let their workers organize into labor unions. 3. Globalization has accelerated the loss of both manufacturing jobs and white-collar jobs overseas. 4. The removal of trade barriers hurts workers in foreign countries, too. For example, NAFTA removed tariffs among Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Because they receive agricultural subsidies from the US government, large American agribusinesses grow corn and wheat for less than its true cost of production and sell the grain in Mexico. Mexican farmers who cannot compete with these prices are driven out of business. Most of them cannot find jobs in Mexico and end up emigrating to the United States [61]. a Even if globalization is a good idea, there are reasons why a company may not choose to move its facilities to the place where labor is the least expensive. Interestingly, these arguments are more relevant to blue-collar jobs such as manufacturing than they are to white-collar jobs such as computer programming. With automation, the cost of labor becomes a smaller percentage of the total cost of a product. Once the labor cost is reduced to a small enough fraction, it makes little difference whether the factory is located in China or the United States. Meanwhile, there are definite additional costs associated with foreign factories. If you include products in transit, foreign factories carry more inventory than identical factories in the United States. There are also more worries about security when the product is being made in a foreign country. For these reasons, moving a factory to a less developed country is not always in the best interest of a company (10). 10.4.3 Dot-Com Bust Increased IT Sector Unemployment In the 1990s, Intel's stock rose 3,900 percent, Microsoft's stock increased in value 7,500 percent, and Cisco Systems' stock soared an incredible 66,000 percent. That means $1,000 of Cisco stock purchased in 1990 was worth $661,000 at the end of 1999. Investors looking for new opportunities for high returns focused on dot-coms, Internet-related start-up companies. Speculators pushed up the values of many companies that had never earned a profit. Early in 2000, the total valuation of 370 Internet start-ups was $1.5 trillion, even though they had only $40 billion in sales (that's sales, not profits) (62). In early 2000, the speculative bubble burst, and the prices of dot-com stocks fell rapidly. The ensuing "dot-com bust" resulted in 862 high-tech start-ups going out of business between January 2000 and June 2002. Across the United States, the high-tech industry shed half a million jobs (63). In San Francisco and Silicon Valley, the dot-com bust resulted in the loss of 13 percent of nonagricultural jobs, the worst downturn since the Great Depression (64). 10.4.4 Foreign Workers in the American IT Industry Even while hundreds of thousands of information technology workers were losing their jobs, US companies hired tens of thousands of foreigners to work in the United States. The US government grants these workers visas allowing them to work in America. The two most common visas are called the H-1B and the L-1. An H-1B visa allows a foreigner to work in the United States for up to six years. In order for a company to get an H-1B visa for a foreign employee, the company must demonstrate that there are no Americans qualified to do the job. The company must also pay the foreign worker the prevailing wage for the job. Information technology companies have made extensive use of H-1B visas to bring in skilled foreign workers and to hire foreign students graduating from US universities. In the midst of the high-tech downturn, the US government continued to issue tens of thousands of H-1B visas: 163,600 in 2000-2001 and 79,100 in 2001-2002. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate among American computer science professionals was about 5.1 percent. Many of the 100,000 unemployed computer scientists complained to Congress about the large number of H-1B visas being issued. Some professional organizations argued against giving out any H-1B visas at all [65]. Congress decided to drop the H-1B quota to 65,000 for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2003, and it initially set a quota of 65,000 for the following fiscal year. However, the 65,000 H-1B visas approved for 2004-2005 were filled in a single day; representatives of universities and technology companies said the quota was set too low [66]. Bill Gates said, Anyone who's got the education and the experience, they're not out there unemployed" [67]. Congress responded in May 2005 by allowing an exemption for an additional 20,000 foreigners with advanced degrees (master's or higher). The annual quota of 65,000 H-1B visas and the exemption for 20,000 foreigners with advanced degrees remain in effect. When the economy is strong, the demand for H-1B visas greatly exceeds the number of visas available, and the federal government holds a lottery to determine which petitions will move forward. In April 2018 the government announced for the sixth year in a row that it would hold a lottery for H-1B visas because in the first five days of accepting visas it had already received more than 85,000 applications [68]. The other important work visa is called the L-1. American companies use L-1 visas to move workers from overseas facilities to the United States for up to seven years. For example, Intel employees in Bangalore, India, could be transferred to Hillsboro, Oregon, if they held an L-1 visa. Employees brought in to the United States under an L-1 visa do not need to be paid the prevailing wage. That saves employers money. Critics of L-1 visas claim lower-paid foreign workers are replacing higher-paid American workers within the walls of high-tech facilities located in the United States. The US Congress has put no limit on the number of L-1 visas that may be issued in any given year, but the number of foreigners working in the United States under L-1 visas is much smaller than the number holding H-1B visas. In 2017 about 78,000 foreigners were employed in the United States under the L-1 visa program (69). 10.4.5 Foreign Competition The debate over the number of visas to grant foreign workers seeking employment in the United States should not mask another trend: the increasing capabilities of IT companies within developing nations, particularly China and India. In 1990 China's computer hardware industry was virtually nonexistent. IBM agreed to sell its PC division to Chinese computer manufacturer Lenovo for $1.75 billion in 2004, making Lenovo the number-three manufacturer of PCs in the world (70). That was the year China became the world's leading producer of personal computer hardware. Today, 90 percent of all personal computers are manufactured in China [71]. India's outsourcing industry is large; Indian companies now employ more than a million people and have annual sales exceeding $60 billion. About two-thirds of these sales are in outsourcing IT work, such as designing, programming, and maintaining computer software. The other third are in outsourcing business processes, such as call centers, medical transcription, and X-ray interpretation [72]. Some Chinese universities are becoming recognized for their research expertise. For example, the Institute of Computing Technology at the Chinese Academy of Science and Tsinghua University have been actively involved in the development of the Open64 optimizing compiler (73). More evidence of global competition comes from the annual Association for Computing Machinery International Collegiate Programming Contest. When the contest began in 1977, only schools from North America and Europe competed. Today it is a truly international competition. In fact, no American team has placed first since Harvey Mudd College in 1997. In the five-year period from 2011 through 2015, only one of the 20 teams earning gold medals was from the United States (74). 10.5 The Digital Divide The digital divide refers to the situation in which some people have access to modern information technology while others do not. The underlying assumption motivating the term is that people who use cell phones, computers, and the Internet have opportunities denied to people without access to these devices. The idea of a digital divide became popular in the mid-1990s with the rapid growth in popularity of the World Wide Web. According to Pippa Norris, the digital divide has two fundamentally different dimensions. The global divide refers to the disparity in Internet access between more industrialized and less industrialized nations. The social divide refers to the difference in access between the rich and poor within a particular country (75). 10.5.1 Global Divide There is plenty of evidence of what Norris calls the global divide. One piece of evidence is the percentage of people with Internet access (Figure 10.80). In 2018 about 4.2 billion people, representing roughly 54 percent of the world's population, had access to the Internet. Access to the Internet in North America and Europe was significantly above this average, while access in Africa was well below (76). Figure 10.8 100 90 80 70 60 Internet access (%) 50 40 30 20 10 0 Africa Asia Middle East Europe Latin America/Caribbean North America Oceania/Australia Percentage of people with Internet access, by world region. What is hampering Internet development in less technologically developed countries? 1. Often there is little wealth. In many of these countries there is not enough money to provide everyone in the country with the necessities of life, much less pay for Internet connections. 2. Many of these countries have an inadequate telecommunications infrastructure. For example, less than 25 percent of the people in the following countries have cell phones: North Korea, Eritrea, Cuba, Kiribati, Somalia, South Sudan, Burundi, Ethiopia, Tuvalu, and Djibouti [77]. Many poor people have no access to newspapers, radio, or television (75). 3. The primary language is not English. English is the dominant language for business and scientific development, giving English-speaking countries a comparative advantage with respect to competing in the global marketplace. 4. Literacy is low and education is inadequate. Half the population in poorer countries has no opportunity to attend secondary schools. There is a strong correlation between literacy and wealth, both for individuals and for societies (37). 5. The country's culture may not make participating in the Information Age a priority (78). 10.5.2 Social Divide Even within wealthy countries such as the United States, the extent to which people use the Internet varies significantly according to age, wealth, and educational achievement. Pew Internet polled Americans to find out how many made use of the Internet as of early 2018. Online access varied from 98 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds to 66 percent of those 65 and over. Fully 98 percent of adults living in households with annual incomes of at least $75,000 used the Internet, compared to 81 percent of adults living in households with annual incomes less than $30,000. While 97 percent of those with a college degree used the Internet, only 65 percent of those who dropped out of high school went online. The report also noted that the less-connected groups are gradually catching up with the more- connected groups (79). 10.5.3 Models of Technological Diffusion New technologies are usually expensive. Hence the first people to adopt new technologies are those who are better off. As the technology matures, its price drops dramatically, enabling more people to acquire it. Eventually, the price of the technology gets low enough that it becomes available to nearly everyone. The history of the consumer VCR illustrates this phenomenon. The first VHS VCR, introduced by RCA in 1977, retailed for $1,000 ($3,562 in 2009 dollars). In 2009 you could buy a VHS VCR from a mass-marketer for under $30. That means between 1977 and 2009, the price of a VCR in constant dollars fell by more than 99 percent! As the price declined, more people could afford to purchase a VCR and sales increased rapidly. The VCR progressed from a luxury that only the rich could afford to a consumer product found in nearly every American household. Technological diffusion refers to the rate at which a new technology is assimilated into a society. Two different theories predict how a new technology is acquired by people in a society, based on their socioeconomic status (Figure 10.90). We divide society into three groups. People with the highest socioeconomic status are in group A, people with the lowest socioeconomic status are in group C, and group B consists of those people in the middle. Figure 10.9 100% 100% , 1 Time Time (b) (a) Two models for technological diffusion. In both models the most advantaged group A is the first to adopt a new technology, while the least advantaged group C is the last to adopt it. (a) In the normalization model, the technology is eventually embraced by nearly everyone in all groups. (b) In the stratification model, the eventual adoption rate of the technology is lower for less advantaged groups. In the normalization model (Figure 10.929), group A begins to adopt the technology first, followed by group B, and finally group C. However, at some point nearly everyone in all three groups is using the new technology. In the stratification model (Figure 10.950), the order of adoption is the same as in the normalization model. However, in this model the eventual number of people in group C who adopt the technology is lower than the number of adopters in group A. The percentage of people in group B who adopt the technology is somewhere between the levels of the other two groups. Technological optimists believe the global adoption of information technology will follow the normalization model. Information technology will make the world a better place by reducing poverty in developing countries. Creating opportunities elsewhere will reduce the number of people trying to immigrate into the United States. Technological pessimists believe information technology adoption will follow the stratification model, leading to a permanent condition of "haves" and "have-nots." Information technology will only exacerbate existing inequalities between rich and poor nations and between rich and poor people within each nation (75). Technological pessimists point out that the gap between the richest 20 countries and the poorest 20 countries continues to grow. In 1960 the average gross domestic product (GDP) of the richest countries was 18 times larger than the average GDP of the poorest countries. By 1995 the gap had grown to 37 times greater. Some of the poorest countries grew even poorer during the last third of the twentieth century [37]. 10.5.4 Critiques of the Digital Divide Mark Warschauer has suggested three reasons why the term "digital divide is not helpful. First, it tends to promote the idea that the difference between the "haves" and the "have- nots is simply a question of access. Some politicians have jumped to the conclusion that providing technology will close the divide. Warschauer says this approach will not work. To back his claim, he gives as an example the story of a small town in Ireland. a While many factories in Ireland produced IT products, there was not a lot of IT use among Irish citizens. Ireland's telecommunications company held a contest in 1997 to select and fund an "Information Age Town." The winner was Ennis, a town of 15,000 in western Ireland. The $22 million in prize money represented $1,200 per resident, a large sum for a poor community. Every business was equipped with an Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) line, a Web site, and a smart card reader. Every family received a smart card and a personal computer. Three years later, there was little evidence of people using the new technology. Devices had been introduced without adequately explaining to the people why they might want to use them. The benefits were not obvious. Sometimes the technology competed with social systems that were working just fine. For example, before the introduction of the new technology, unemployed workers visited the social welfare office three times a week to sign in and get an unemployment payment. These visits served an important social function for the unemployed people. It gave them an opportunity to visit with other people and keep their spirits up. Once the PCs were introduced, the workers were supposed to "sign in" and receive their payments over the Internet. Many of the workers did not like the new system. It appears that many of the PCs were sold on the black market. The unemployed workers simply went back to reporting in person to the social welfare office. For IT to make a difference, social systems must change as well. The introduction of information technology must take into account local culture, which includes language, literacy, and community values. Warschauer's second criticism of the term "digital divide" is that it implies everyone is on one side or another of a huge canyon. Everybody is put into one of two categories: "haves" and "have-nots." In reality access is a continuum, and each individual occupies a particular place on it. For example, how do you categorize someone who has a 56 K modem connecting his PC to the Internet? Certainly, that person has online access, but he is not able to retrieve the same wealth of material as someone with a broadband connection. Third, Warschauer says that the term "digital divide" implies that a lack of access will lead to a less advantaged position in society. Is that the proper causality? Models of technological diffusion show that those with a less advantaged position in society tend to adopt new technologies at a later time, which is an argument that the causality goes the other way. In reality, there is no simple causality. Each factor affects the other (37). a Rob Kling has put it this way: [The] big problem with the digital divide" framing is that it tends to connote "digital solutions," i.e., computers and telecommunications, without engaging the important set of complementary resources and complex interventions to support social inclusion, of which informational technology applications may be enabling elements, but are certainly insufficient when simply added to the status quo mix of resources and relationships. [37, pp. 7-8] Finally, Warschauer points out that the Internet does not represent the pinnacle of information technology. In the next few decades, dramatic new technologies will be created. We will see these new technologies being adopted at different speeds, too. 10.5.5 Massive Open Online Courses For the past several decades, the rate of tuition increases at universities and colleges in the United States has exceeded the inflation rate, making a college education increasingly difficult for students from poorer families. Free massive open online courses (MOOCs) are often promoted as a way to make higher education more affordable, which would help all students, but particuarly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. In 2012 Colorado State University-Global became the first university in the United States to grant credit to students completing a particular MOOC in computer science (80). Other universities are likely to follow. Is solving the problem of ever more expensive higher education as simple as providing access to online courses? The Community College Research Center conducted a study of online education at two statewide community systems, one in the southern United States and the other in the western United States. Their study revealed that students who take online courses are less likely to complete and perform well in them, compared with students who take the same courses in a traditional classroom setting. The study also showed that the online experience widened the achievement gap between white and black students and between those with higher GPAs and those with lower GPAs (81). The Community College Research Center study provides evidence that a shift toward online education could exacerbate differences in success rates that already exist between different subgroups of students. It reinforces Warschauer's point that the difference between the "haves" and the "have-nots" in society is not simply a question of access to a technology or even information. 10.5.6 Net Neutrality In the middle of the last decade, corporations that operate the long-distance Internet backbone connections in the United States suggested that they might begin tiered service- charging more for higher-priority routing of Internet packets. These companies said that tiered service would be needed in the future to guarantee a satisfactory level of service to companies that require it, such as voice over Internet protocol (VoIP) providers (82). Content providers such as Google and Yahoo joined forces with the American Library Association and consumer groups to oppose any notion of tiered service. These groups asked the US Congress to enact "net neutrality legislation that would require Internet service providers to treat all packets the same. Consumer groups suggested that if tiered service were enacted, only large corporations would be able to pay for the highest level of service. Small start-up companies wouldn't be able to compete with established corporate giants. Hence tiered service would discourage innovation and competition. Another argument against tiered service was based on the concern that companies controlling the Internet might block or degrade access to nonfavored content or applications [82]. For example, a customer with an AT&T/Yahoo DSL connection might find that high-definition video content from AT&T channels performs better than high-definition video from other providers (83). Net neutrality advocates said this would be unfair and should be prevented, pointing out that 95 percent of consumers have only two choices for broadband access: the local cable company or the local telephone company [84]. Opponents of net neutrality legislation suggested that allowing people to pay more to get a higher quality of service can benefit consumers. For example, rapid delivery of data packets would be more valuable to a person using the Internet for videoconferencing than a person who simply sends email messages. Internet backbone providers argued that even though there was currently enough bandwidth, the rapidly increasing popularity of YouTube and other online video sites would soon fill the Internet's data pipes. A significant amount of money would be needed to upgrade the Internet infrastructure to support the higher- bandwidth applications of the future. This money ought to come from the companies like Netflix that sell access to data-intensive content (82). In February 2015, during the administration of President Barack Obama, the Federal Communications Commission issued the Open Internet Order to preserve net neutrality. It prohibited telecommunications companies from engaging in three activities: blocking content, throttling back the speed of transmissions, and providing a higher speed of service to people or businesses that pay more [85]. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler said, No one- whether government or corporate-should control free, open access to the Internet" [86]. The FCC grounded its authority make these rules on Title II of the Telecommunications Act, in effect deciding that the Internet should be regulated as a public utility. The FCC's decision was immediately hailed by some groups and criticized by others. Netflix issued a statement saying, "The net neutrality debate is about who picks winners and losers online: Internet service providers or consumers. Today the FCC settled it: Consumers win" [87]. Meanwhile, Broadband for America, an advocacy group that has Internet service providers among its members, issued a statement saying, The FCC's decision to impose obsolete telephone-era regulations on the high-speed Internet is one giant step backwards for America's broadband networks and everyone who depends upon them. These 'Title II rules go far beyond protecting the Open Internet, launching a costly and destructive era of government micromanagement that will discourage private investment in new networks and slow down the breakneck innovation that is the soul of the Internet today" [88]. Under the administration of President Donald Trump, the FCC changed course, and in December 2017 the commissioners voted to repeal the net neutrality rules put in place by the Obama administration. The repeal took effect in June 2018 (89). Responding to the FCC's decision, lawmakers in dozens of states introduced legislation to preserve net neutrality rules. In March 2018 the state of Washington became the first state to preserve for its residents the net neutrality rules established by the FCC in 2015 (90)Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started