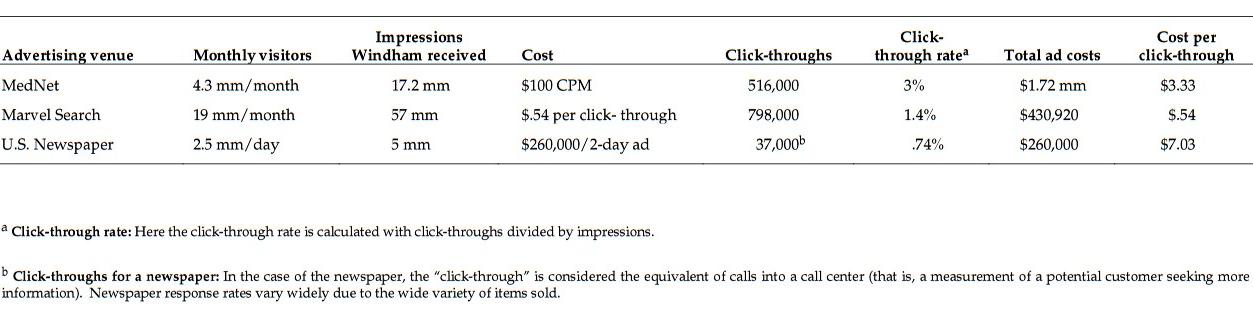

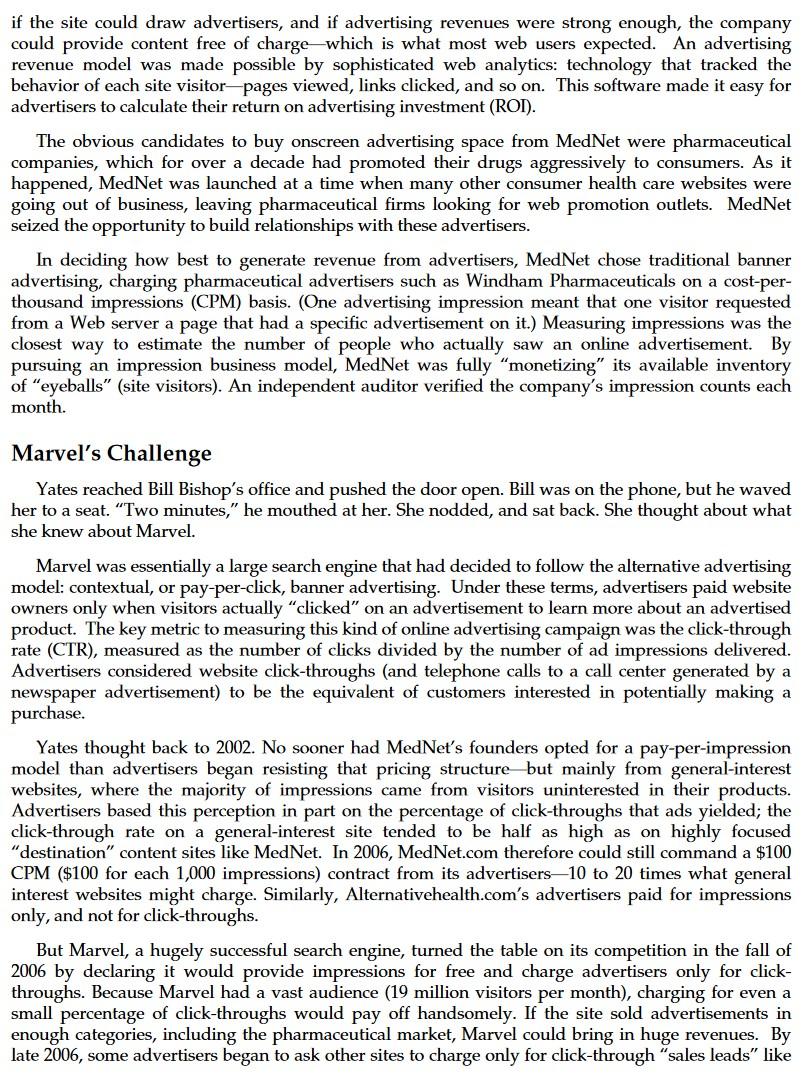

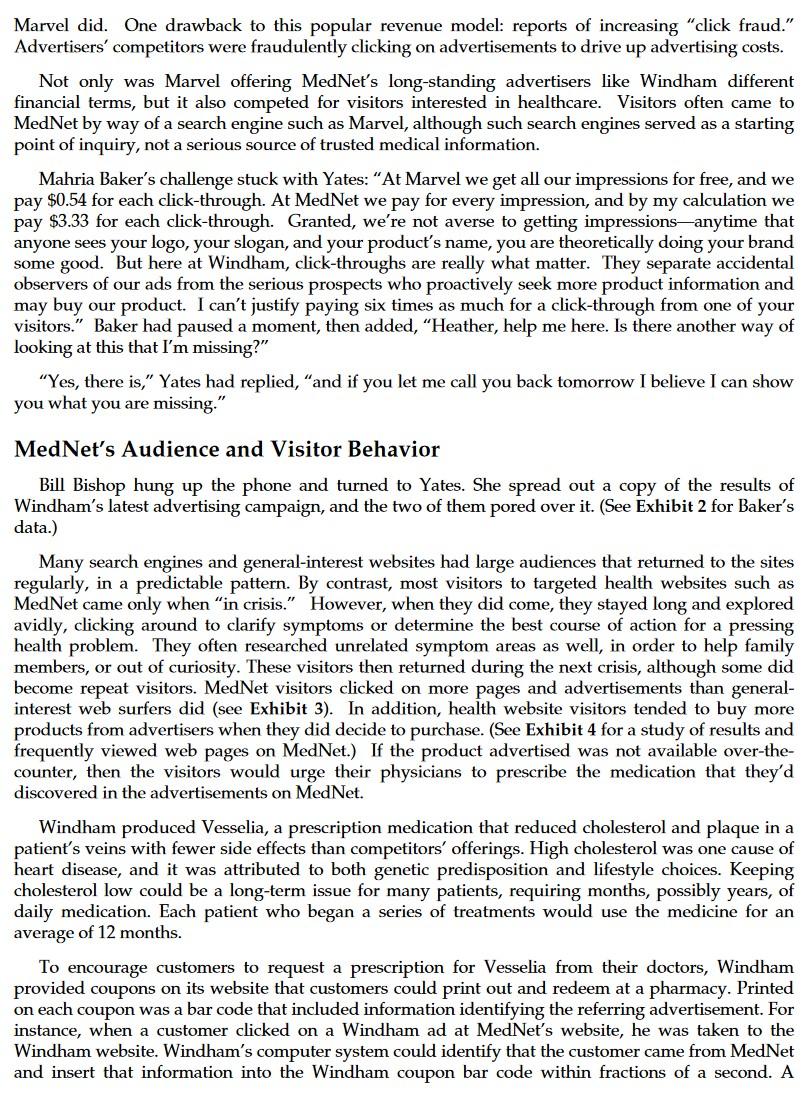

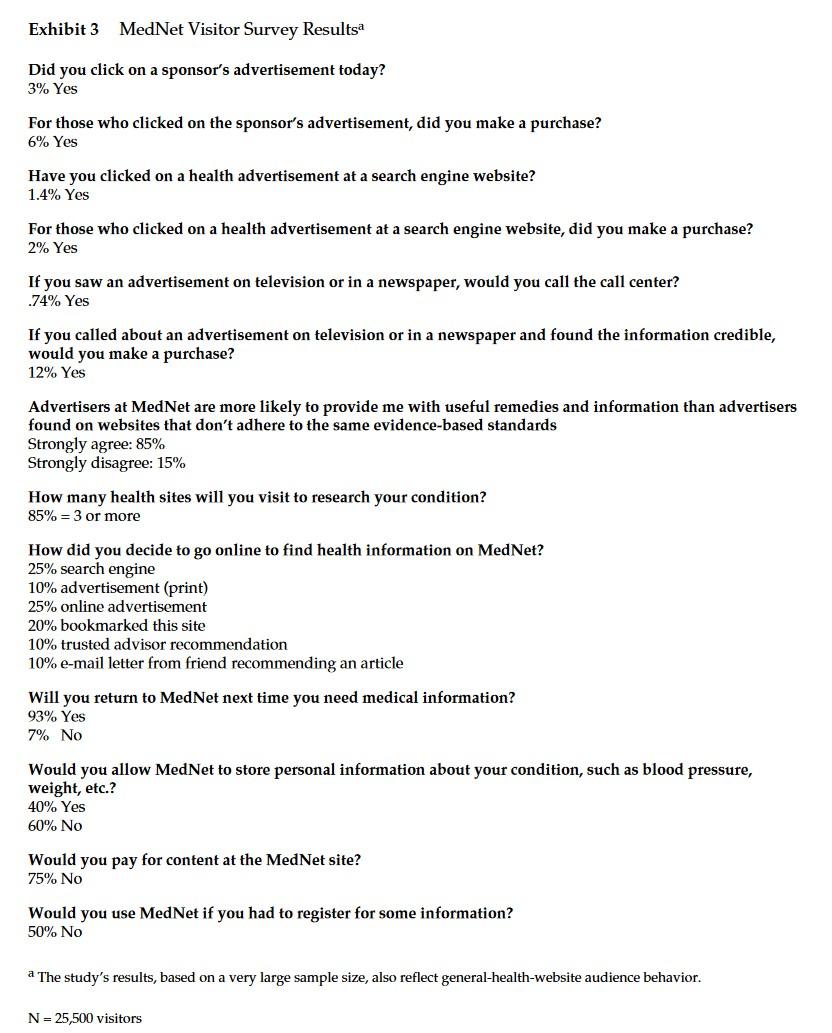

Read the following case and fill in the excel sheet below. Determine Windham's income, profit, and ROI from each medium:

Exhibit 2

| Use information from the case and appropriate calculations to determine Windham's income, profit, and ROI from each medium. Use cell locations in any formula you apply to show how calculations were made. Note: you may want to add columns to your spreadsheet. |

| Media | Cost/Click through | % who buy | New customers | Contribution per sale | Income | Profit | ROI |

| MedNet | | | | | | | |

| Marvel Search | | | | | | | |

| U.S. Newspaper | | | | | | | |

| Source | Exhibit 2 | Exhibit 3 | Calculation | Exhibit 4 | Calculation | Calculation | Calculation |

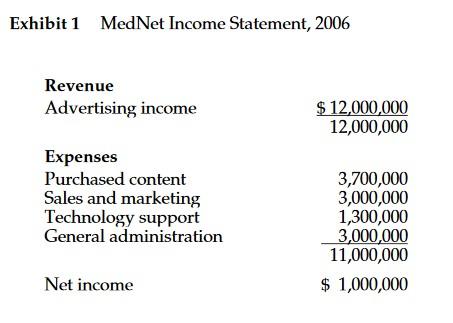

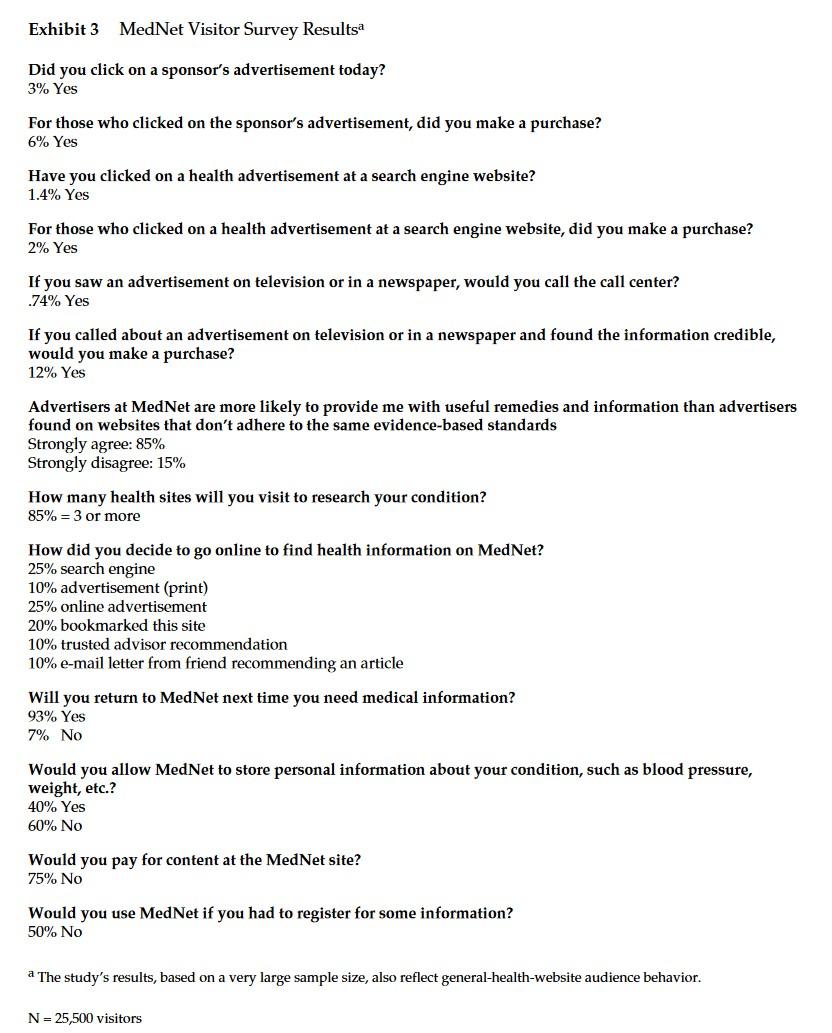

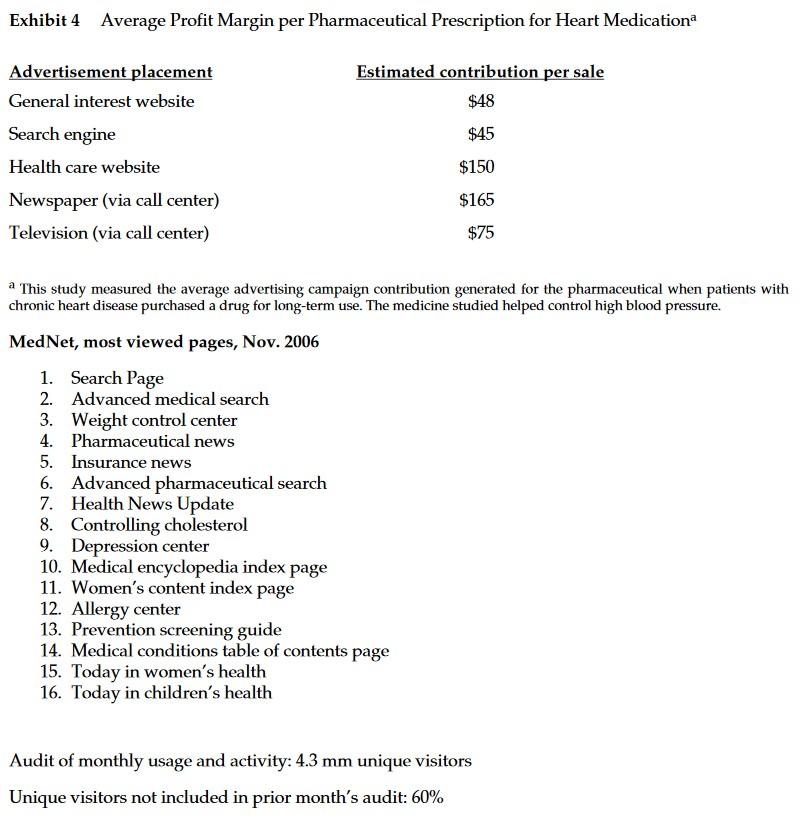

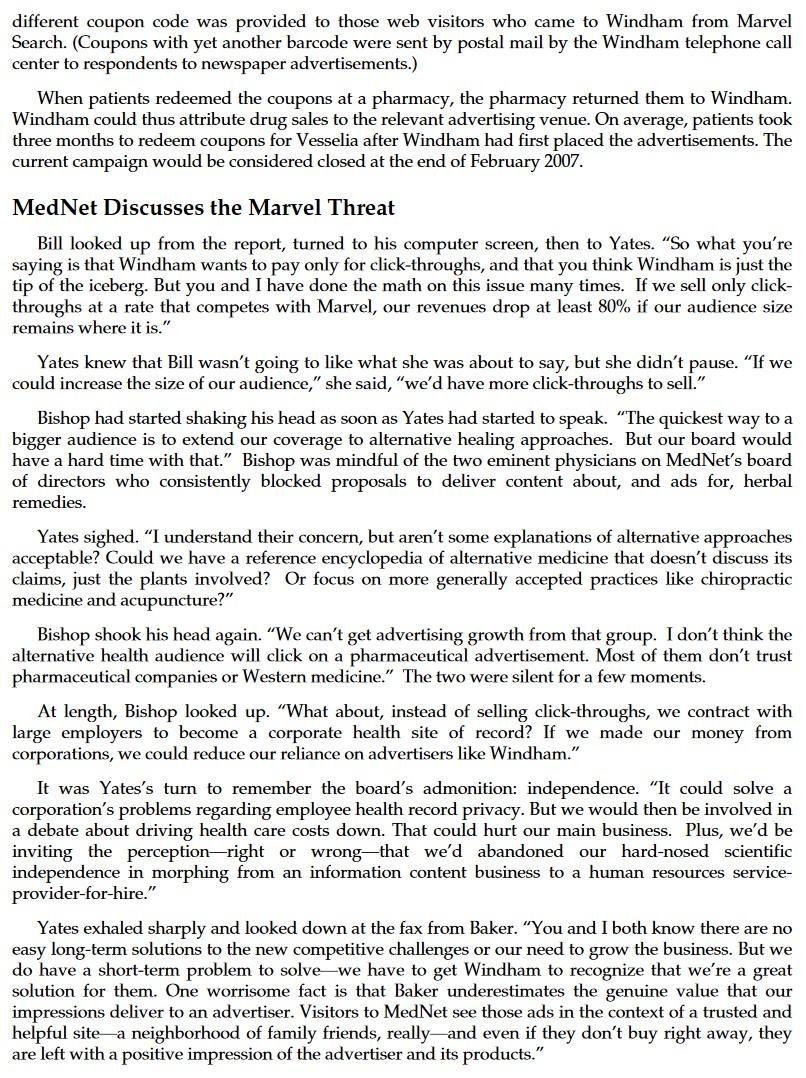

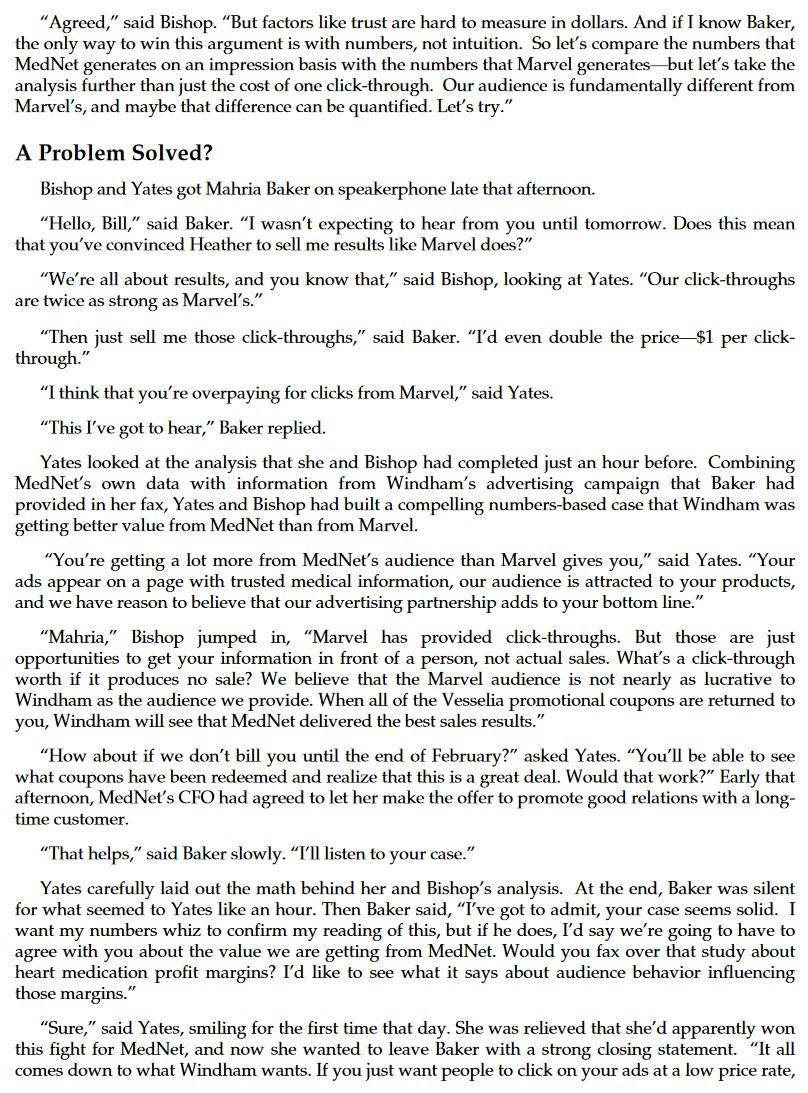

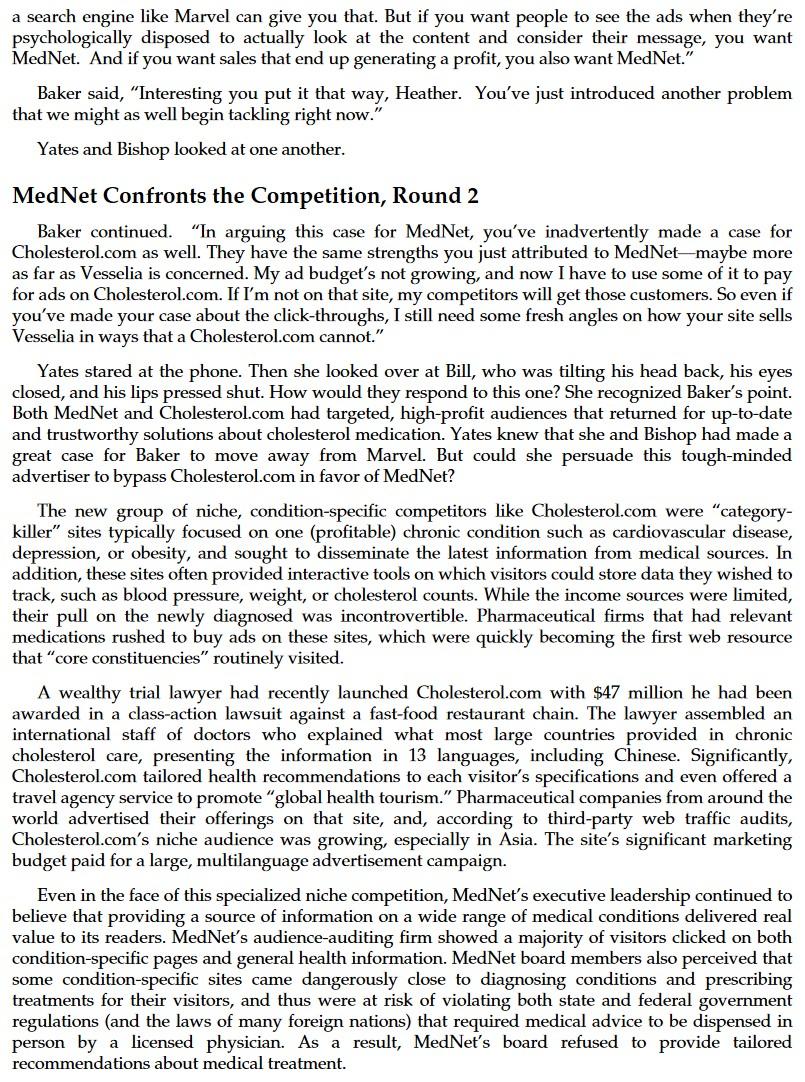

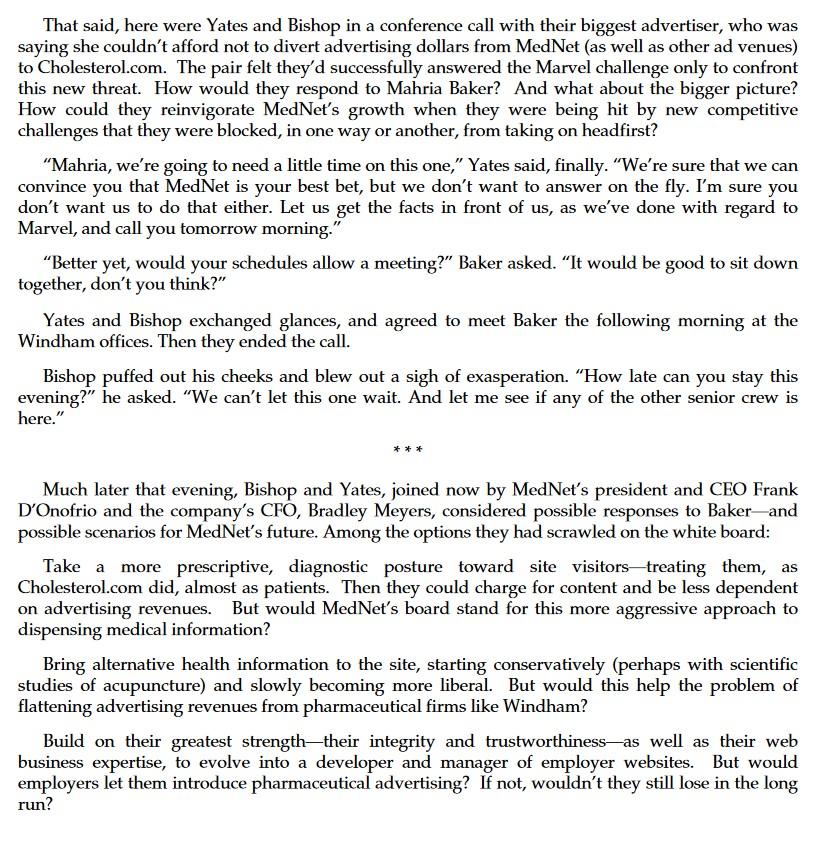

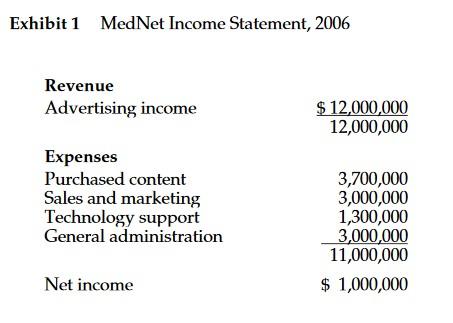

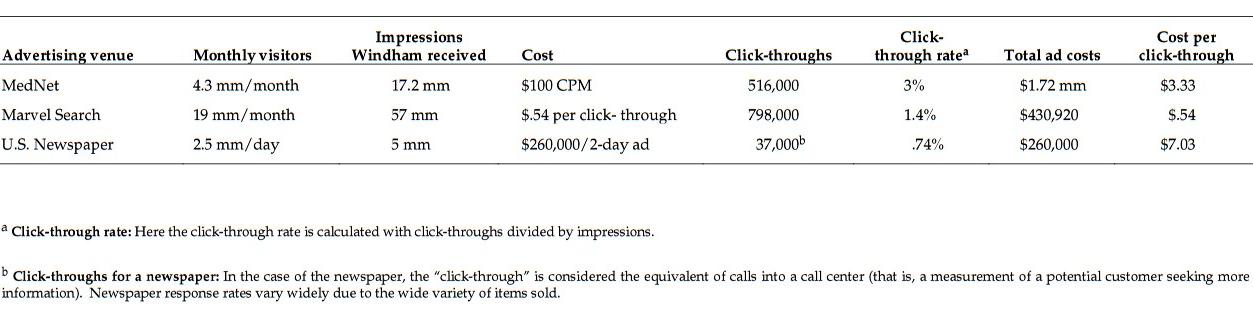

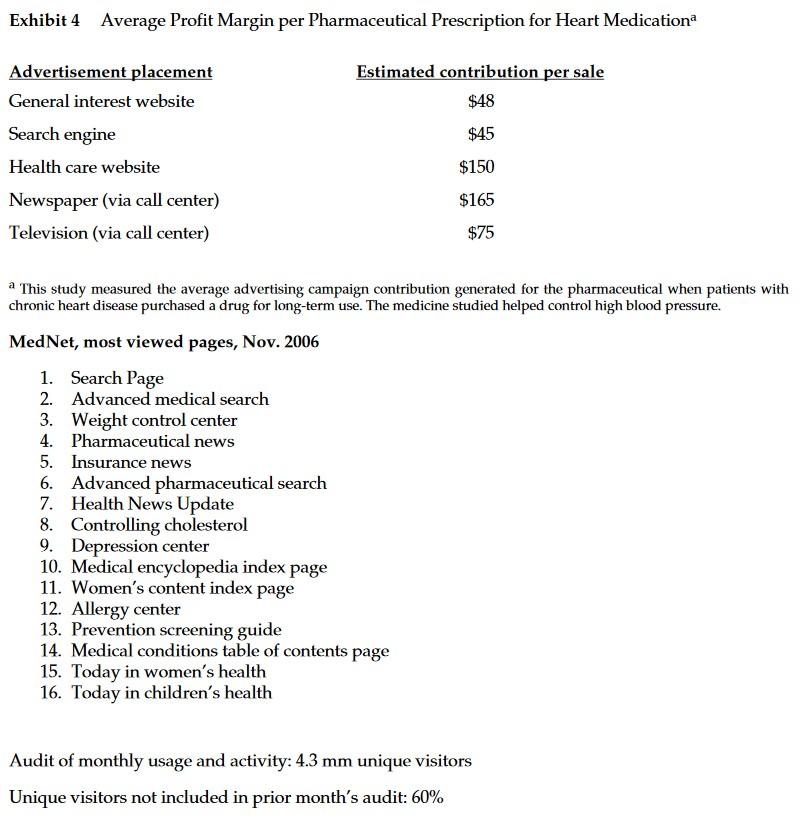

MedNet.com Confronts Click-Through Competition It was just 9:30 a.m., and the day was off to a terrible start. Heather Yates, vice president for business development at MedNet, walked at a quick clip down the hall of the company's modern Birmingham, Alabama, office space, her face clouded with concern. The company, a website delivering health information free to consumers, generated its income through advertising, mostly from pharmaceutical companies. Now, Windham Pharmaceuticals, MedNet's biggest advertiser, had asked to change the rules by which it had done business for the past four years. Moreover, Mahria Baker, Windham's CMO, had told Yates that this wasn't just an exploratory conversation. Windham was seriously considering shifting its MedNet ad dollars to Marvel, a competing website with which Windham already did some business. Yates, who had been with MedNet since just after the company was founded in 2002, felt blindsided and, at the same time, resigned. We have some legwork to do," she thought to herself. "We can't afford to say 'No,' and just walk away, and we can't just ask them to stay with us because we're good people. We have to convince them that our set-up is worth their ad dollars. And we have to move quickly. Our other advertisers won't be far behind Windham." She had asked Baker to fax over a copy of the results of Windham's latest advertising campaign, and had promised to call her back the next day, as both companies needed to finalize their budgets. Then, immediately after they had hung up, Yates had called Bill Bishop, MedNet's vice president of consumer marketing. "Can you clear some time for me right now?" she had asked him. "Windham is thinking of pulling their ad dollars from us and taking them to Marvel." Now she was on her way up to Bishop's office, two floors above, with the fax from Baker and notes from her conversation in hand. Industry Background and Company Origins MedNet had launched its website with three goals: to provide scientifically based medical information to a nonprofessional consumer audience; to provide this information for free; and to generate profits from advertising sales. In a year, it had met all the goals; by 2006, it generated $1 million in profits. (See Exhibit 1 for 2006 income statement.) The accessibly written, easy-to- navigate, and vividly presented content was developed by 24 trained journalists, doctors, designers, and administrators. Additional materials came from the faculty of a prominent medical school, news agencies, a photography service, and an active community of visitors that used social media tools such as blogs, community chat, and virtual reality to communicate medical information. (Visitor- generated media was reviewed by medically trained journalists.) The award-winning site was considered the best health website for trusted, evidence-based, consumer health information. Advertisements on MedNet proposed specific and immediate solutions to health concerns. MedNet had 4.3 million monthly visitors, but new competitors had flattened its audience growth during the last quarter of 2006. Competitors Now, in the first quarter of 2007, MedNet faced competition both for visitors and advertisers. Nonprofit and governmental websites competed with MedNet for visitors by providing similar content on mainstream medicine. The websites of the U.S. National Library of Medicine and World Health Organization weren't nearly as easy to navigate as MedNet, but they were comprehensive. In contrast to MedNet, these two websites provided information on alternative therapies as well as on scientifically based solutions, albeit with carefully worded disclaimers. What's more, employees of large corporations could increasingly turn to customized health websites on their own company intranets. The theory was that if internal health websites could help workers quickly identify health problems (prompting overdue doctor visits) and promote general good health, the employers could reduce their portion of employee health care costs. For-profit health websites posed different degrees of financial competition for MedNet's advertising revenue and audience. Recently, so-called condition-specific sites that focused on particular problems, such as Cholesterol.com, had emerged. (Yates was confident that Cholesterol.com was already drawing pharmaceutical advertising dollars away from MedNet.) An indirect competitor, ClinicalTrials.com, marketed only experimental procedures. Its audience was smaller than MedNet's and the material was difficult for the layperson to understand. ClinicalTrials.com received a fee for each time a visitor it referred enrolled in a clinical trial. Then there was Alternativehealth.com, a long-time, popular player in the "health space." It provided information about scientifically "unproven" therapies and procedures such as herbal remedies, vitamin regimens, and massage. Its audience was larger than MedNet's and its advertising sales more robust. Due to a recent lawsuit concerning its content, Alternativehealth.com had begun using disclaimerswith no apparent impact on its audience size. Due to the alternative health consumer's distrust of pharmaceutical companies, the website did not compete with MedNet for advertising dollars. Still, MedNet had to keep Alternativehealth on its radar. Methods Used to Calculate Advertiser Payment Yates's thoughts raced through the company's competitive landscape as she waited for the elevator. In her short phone conversation with Bill, he had told her to take a little time to review MedNet's original value proposition to its advertisers. What they needed to do was re-justify their approach, if it was possible to do so. But, he had cautioned, they were compelled to keep an open mind. "Think through the facts," Bill had said. "Why don't you come up here in about half an hour. I'll start to mull over our options as well." Yates thought back to MedNet's roots. Back in 2002, MedNet's founders had made some key choices regarding revenue generation. MedNet could, in theory, sell content to site visitors, like an online magazine, charging a few dollars per article or an annual subscription fee. On the other hand, if the site could draw advertisers, and if advertising revenues were strong enough, the company could provide content free of charge which is what most web users expected. An advertising revenue model was made possible by sophisticated web analytics: technology that tracked the behavior of each site visitor-pages viewed, links clicked, and so on. This software made it easy for advertisers to calculate their return on advertising investment (ROI). The obvious candidates to buy onscreen advertising space from MedNet were pharmaceutical companies, which for over a decade had promoted their drugs aggressively to consumers. As it happened, MedNet was launched at a time when many other consumer health care websites were going out of business, leaving pharmaceutical firms looking for web promotion outlets. MedNet seized the opportunity to build relationships with these advertisers. In deciding how best to generate revenue from advertisers, MedNet chose traditional banner advertising, charging pharmaceutical advertisers such as Windham Pharmaceuticals on a cost-per- thousand impressions (CPM) basis. (One advertising impression meant that one visitor requested from a Web server a page that had a specific advertisement on it.) Measuring impressions was the closest way to estimate the number of people who actually saw an online advertisement. By pursuing an impression business model, MedNet was fully "monetizing" its available inventory of eyeballs (site visitors). An independent auditor verified the company's impression counts each month. Marvel's Challenge Yates reached Bill Bishop's office and pushed the door open. Bill was on the phone, but he waved her to a seat. Two minutes," he mouthed at her. She nodded, and sat back. She thought about what she knew about Marvel. Marvel was essentially a large search engine that had decided to follow the alternative advertising model: contextual, or pay-per-click, banner advertising. Under these terms, advertisers paid website owners only when visitors actually clicked" on an advertisement to learn more about an advertised product. The key metric to measuring this kind of online advertising campaign was the click-through rate (CTR), measured as the number of clicks divided by the number of ad impressions delivered. Advertisers considered website click-throughs (and telephone calls to a call center generated by a newspaper advertisement) to be the equivalent of customers interested in potentially making a purchase. Yates thought back to 2002. No sooner had MedNet's founders opted for a pay-per-impression model than advertisers began resisting that pricing structure but mainly from general-interest websites, where the majority of impressions came from visitors uninterested in their products. Advertisers based this perception in part on the percentage of click-throughs that ads yielded; the click-through rate on a general-interest site tended to be half as high as on highly focused "destination" content sites like MedNet. In 2006, MedNet.com therefore could still command a $100 CPM ($100 for each 1,000 impressions) contract from its advertisers10 to 20 times what genera interest websites might charge. Similarly, Alternativehealth.com's advertisers paid for impressions only, and not for click-throughs. But Marvel, a hugely successful search engine, turned the table on its competition in the fall of 2006 by declaring it would provide impressions for free and charge advertisers only for click- throughs. Because Marvel had a vast audience (19 million visitors per month), charging for even a small percentage of click-throughs would pay off handsomely. If the site sold advertisements in enough categories, including the pharmaceutical market, Marvel could bring in huge revenues. By late 2006, some advertisers began to ask other sites to charge only for click-through sales leads like Marvel did. One drawback to this popular revenue model: reports of increasing "click fraud." Advertisers' competitors were fraudulently clicking on advertisements to drive up advertising costs. Not only was Marvel offering MedNet's long-standing advertisers like Windham different financial terms, but it also competed for visitors interested in healthcare. Visitors often came to MedNet by way of a search engine such as Marvel, although such search engines served as a starting point of inquiry, not a serious source of trusted medical information. Mahria Baker's challenge stuck with Yates: "At Marvel we get all our impressions for free, and we pay $0.54 for each click-through. At MedNet we pay for every impression, and by my calculation we pay $3.33 for each click-through. Granted, we're not averse to getting impressions anytime that anyone sees your logo, your slogan, and your product's name, you are theoretically doing your brand some good. But here at Windham, click-throughs are really what matter. They separate accidental observers of our ads from the serious prospects who proactively seek more product information and may buy our product. I can't justify paying six times as much for a click-through from one of your visitors." Baker had paused a moment, then added, Heather, help me here. Is there another way of looking at this that I'm missing?" Yes, there is," Yates had replied, and if you let me call you back tomorrow I believe I can show you what you are missing." MedNet's Audience and Visitor Behavior Bill Bishop hung up the phone and turned to Yates. She spread out a copy of the results of Windham's latest advertising campaign, and the two of them pored over it. (See Exhibit 2 for Baker's data.) Many search engines and general-interest websites had large audiences that returned to the sites regularly, in a predictable pattern. By contrast, most visitors to targeted health websites such as MedNet came only when "in crisis. However, when they did come, they stayed long and explored avidly, clicking around to clarify symptoms or determine the best course of action for a pressing health problem. They often researched unrelated symptom areas as well, in order to help family members, or out of curiosity. These visitors then returned during the next crisis, although some did become repeat visitors. MedNet visitors clicked on more pages and advertisements than general- interest web surfers did (see Exhibit 3). In addition, health website visitors tended to buy more products from advertisers when they did decide to purchase. (See Exhibit 4 for a study of results and frequently viewed web pages on MedNet.) If the product advertised was not available over-the- counter, then the visitors would urge their physicians to prescribe the medication that they'd discovered in the advertisements on MedNet. Windham produced Vesselia, a prescription medication that reduced cholesterol and plaque in a patient's veins with fewer side effects than competitors' offerings. High cholesterol was one cause of heart disease, and it was attributed to both genetic predisposition and lifestyle choices. Keeping cholesterol low could be a long-term issue for many patients, requiring months, possibly years, of daily medication. Each patient who began a series of treatments would use the medicine for an average of 12 months. To encourage customers to request a prescription for Vesselia from their doctors, Windham provided coupons on its website that customers could print out and redeem at a pharmacy. Printed on each coupon was a bar code that included information identifying the referring advertisement. For instance, when a customer clicked on a Windham ad at MedNet's website, he was taken to the Windham website. Windham's computer system could identify that the customer came from MedNet and insert that information into the Windham coupon bar code within fractions of a second. A different coupon code was provided to those web visitors who came to Windham from Marvel Search. (Coupons with yet another barcode were sent by postal mail by the Windham telephone call center to respondents to newspaper advertisements.) When patients redeemed the coupons at a pharmacy, the pharmacy returned them to Windham. Windham could thus attribute drug sales to the relevant advertising venue. On average, patients took three months to redeem coupons for Vesselia after Windham had first placed the advertisements. The current campaign would be considered closed at the end of February 2007. MedNet Discusses the Marvel Threat Bill looked up from the report, turned to his computer screen, then to Yates. So what you're saying is that Windham wants to pay only for click-throughs, and that you think Windham is just the tip of the iceberg. But you and I have done the math on this issue many times. If we sell only click- throughs at a rate that competes with Marvel, our revenues drop at least 80% if our audience size remains where it is." Yates knew that Bill wasn't going to like what she was about to say, but she didn't pause. "If we could increase the size of our audience," she said, "we'd have more click-throughs to sell." Bishop had started shaking his head as soon as Yates had started to speak. The quickest way to a bigger audience is to extend our coverage to alternative healing approaches. But our board would have a hard time with that." Bishop was mindful of the two eminent physicians on MedNet's board of directors who consistently blocked proposals to deliver content about, and ads for, herbal remedies. Yates sighed. "I understand their concern, but aren't some explanations of alternative approaches acceptable? Could we have a reference encyclopedia of alternative medicine that doesn't discuss its claims, just the plants involved? Or focus on more generally accepted practices like chiropractic medicine and acupuncture?" Bishop shook his head again. "We can't get advertising growth from that group. I don't think the alternative health audience will click on a pharmaceutical advertisement. Most of them don't trust pharmaceutical companies or Western medicine." The two were silent for a few moments. At length, Bishop looked up. "What about, instead of selling click-throughs, we contract with large employers to become a corporate health site of record? If we made our money from corporations, we could reduce our reliance on advertisers like Windham." It was Yates's turn to remember the board's admonition: independence. "It could solve a corporation's problems regarding employee health record privacy. But we would then be involved in a debate about driving health care costs down. That could hurt our main business. Plus, we'd be inviting the perception-right or wrongthat we'd abandoned our hard-nosed scientific independence in morphing from an information content business to a human resources service- provider-for-hire." Yates exhaled sharply and looked down at the fax from Baker. "You and I both know there are no easy long-term solutions to the new competitive challenges or our need to grow the business. But we do have a short-term problem to solve we have to get Windham to recognize that we're a great solution for them. One worrisome fact is that Baker underestimates the genuine value that our impressions deliver to an advertiser. Visitors to MedNet see those ads in the context of a trusted and helpful site-a neighborhood of family friends, reallyand even if they don't buy right away, they are left with a positive impression of the advertiser and its products." "Agreed," said Bishop. "But factors like trust are hard to measure in dollars. And if I know Baker, the only way to win this argument is with numbers, not intuition. So let's compare the numbers that MedNet generates on an impression basis with the numbers that Marvel generates but let's take the analysis further than just the cost of one click-through. Our audience is fundamentally different from Marvel's, and maybe that difference can be quantified. Let's try." A Problem Solved? Bishop and Yates got Mahria Baker on speakerphone late that afternoon. "Hello, Bill," said Baker. I wasn't expecting to hear from you until tomorrow. Does this mean that you've convinced Heather to sell me results like Marvel does?" "We're all about results, and you know that," said Bishop, looking at Yates. "Our click-throughs are twice as strong as Marvel's." Then just sell me those click-throughs," said Baker. "I'd even double the price_$1 per click- through." I think that you're overpaying for clicks from Marvel," said Yates. "This I've got to hear," Baker replied. Yates looked at the analysis that she and Bishop had completed just an hour before. Combining MedNet's own data with information from Windham's advertising campaign that Baker had provided in her fax, Yates and Bishop had built a compelling numbers-based case that Windham was getting better value from MedNet than from Marvel. "You're getting a lot more from MedNet's audience than Marvel gives you," said Yates. "Your ads appear on a page with trusted medical information, our audience is attracted to your products, and we have reason to believe that our advertising partnership adds to your bottom line." "Mahria," Bishop jumped in, "Marvel has provided click-throughs. But those are just opportunities to get your information in front of a person, not actual sales. What's a click-through worth if it produces no sale? We believe that the Marvel audience is not nearly as lucrative to Windham as the audience we provide. When all of the Vesselia promotional coupons are returned to you, Windham will see that MedNet delivered the best sales results." How about if we don't bill you until the end of February?" asked Yates. "You'll be able to see what coupons have been redeemed and realize that this is a great deal. Would that work?" Early that afternoon, MedNet's CFO had agreed to let her make the offer to promote good relations with a long- time customer. "That helps," said Baker slowly. "I'll listen to your case." Yates carefully laid out the math behind her and Bishop's analysis. At the end, Baker was silent for what seemed to Yates like an hour. Then Baker said, "I've got to admit, your case seems solid. I want my numbers whiz to confirm my reading of this, but if he does, I'd say we're going to have to agree with you about the value we are getting from MedNet. Would you fax over that study about heart medication profit margins? I'd like to see what it says about audience behavior influencing those margins." "Sure," said Yates, smiling for the first time that day. She was relieved that she'd apparently won this fight for MedNet, and now she wanted to leave Baker with a strong closing statement. "It all comes down to what Windham wants. If you just want people to click on your ads at a low price rate, a search engine like Marvel can give you that. But if you want people to see the ads when they're psychologically disposed to actually look at the content and consider their message, you want MedNet. And if you want sales that end up generating a profit, you also want MedNet." Baker said, "Interesting you put it that way, Heather. You've just introduced another problem that we might as well begin tackling right now." Yates and Bishop looked at one another. MedNet Confronts the Competition, Round 2 Baker continued. In arguing this case for MedNet, you've inadvertently made a case for Cholesterol.com as well. They have the same strengths you just attributed to MedNet-maybe more as far as Vesselia is concerned. My ad budget's not growing, and now I have to use some of it to pay for ads on Cholesterol.com. If I'm not on that site, my competitors will get those customers. So even if you've made your case about the click-throughs, I still need some fresh angles on how your site sells Vesselia in ways that a Cholesterol.com cannot." Yates stared at the phone. Then she looked over at Bill, who was tilting his head back, his eyes closed, and his lips pressed shut. How would they respond to this one? She recognized Baker's point. Both MedNet and Cholesterol.com had targeted, high-profit audiences that returned for up-to-date and trustworthy solutions about cholesterol medication. Yates knew that she and Bishop had made a great case for Baker to move away from Marvel. But could she persuade this tough-minded advertiser to bypass Cholesterol.com in favor of MedNet? The new group of niche, condition-specific competitors like Cholesterol.com were "category- killer" sites typically focused on one (profitable) chronic condition such as cardiovascular disease, depression, or obesity, and sought to disseminate the latest information from medical sources. In addition, these sites often provided interactive tools on which visitors could store data they wished to track, such as blood pressure, weight, or cholesterol counts. While the income sources were limited, their pull on the newly diagnosed was incontrovertible. Pharmaceutical firms that had relevant medications rushed to buy ads on these sites, which were quickly becoming the first web resource that "core constituencies" routinely visited. A wealthy trial lawyer had recently launched Cholesterol.com with $47 million he had been awarded in a class-action lawsuit against a fast-food restaurant chain. The lawyer assembled an international staff of doctors who explained what most large countries provided in chronic cholesterol care, presenting the information in 13 languages, including Chinese. Significantly, Cholesterol.com tailored health recommendations to each visitor's specifications and even offered a travel agency service to promote "global health tourism." Pharmaceutical companies from around the world advertised their offerings on that site, and, according to third-party web traffic audits, Cholesterol.com's niche audience was growing, especially in Asia. The site's significant marketing budget paid for a large, multilanguage advertisement campaign. Even in the face of this specialized niche competition, MedNet's executive leadership continued to believe that providing a source of information on a wide range of medical conditions delivered real value to its readers. MedNet's audience-auditing firm showed a majority of visitors clicked on both condition-specific pages and general health information. MedNet board members also perceived that some condition-specific sites came dangerously close to diagnosing conditions and prescribing treatments for their visitors, and thus were at risk of violating both state and federal government regulations (and the laws of many foreign nations) that required medical advice to be dispensed in person by a licensed physician. As a result, MedNet's board refused to provide tailored recommendations about medical treatment. That said, here were Yates and Bishop in a conference call with their biggest advertiser, who was saying she couldn't afford not to divert advertising dollars from MedNet (as well as other ad venues) to Cholesterol.com. The pair felt they'd successfully answered the Marvel challenge only to confront this new threat. How would they respond to Mahria Baker? And what about the bigger picture? How could they reinvigorate MedNet's growth when they were being hit by new competitive challenges that they were blocked, in one way or another, from taking on headfirst? "Mahria, we're going to need a little time on this one," Yates said, finally. "We're sure that we can convince you that MedNet is your best bet, but we don't want to answer on the fly. I'm sure you don't want us to do that either. Let us get the facts in front of us, as we've done with regard to Marvel, and call you tomorrow morning." Better yet, would your schedules allow a meeting?" Baker asked. It would be good to sit down together, don't you think?" Yates and Bishop exchanged glances, and agreed to meet Baker the following morning at the Windham offices. Then they ended the call. Bishop puffed out his cheeks and blew out a sigh of exasperation. "How late can you stay this evening?" he asked. "We can't let this one wait. And let me see if any of the other senior crew is here." *** Much later that evening, Bishop and Yates, joined now by MedNet's president and CEO Frank D'Onofrio and the company's CFO, Bradley Meyers, considered possible responses to Baker-and possible scenarios for MedNet's future. Among the options they had scrawled on the white board: Take a more prescriptive, diagnostic posture toward site visitors treating them, as Cholesterol.com did, almost as patients. Then they could charge for content and be less dependent on advertising revenues. But would MedNet's board stand for this more aggressive approach to dispensing medical information? Bring alternative health information to the site, starting conservatively (perhaps with scientific studies of acupuncture) and slowly becoming more liberal. But would this help the problem of flattening advertising revenues from pharmaceutical firms like Windham? Build on their greatest strengththeir integrity and trustworthinessas well as their web business expertise, to evolve into a developer and manager of employer websites. But would employers let them introduce pharmaceutical advertising? If not, wouldn't they still lose in the long run? Exhibit 1 MedNet Income Statement, 2006 Revenue Advertising income $ 12,000,000 12,000,000 Expenses Purchased content Sales and marketing Technology support General administration 3,700,000 3,000,000 1,300,000 3,000,000 11,000,000 $ 1,000,000 Net income Cost per Impressions Windham received Monthly visitors Click- through ratea Cost Total ad costs Advertising venue MedNet Click-throughs 516,000 click-through $3.33 4.3 mm/month 17.2 mm $100 CPM 3% $1.72 mm Marvel Search 19 mm/month 57 mm 1.4% $430,920 $.54 $.54 per click-through $260,000/2-day ad 798,000 37,000b U.S. Newspaper 2.5 mm/day 5 mm .74% $260,000 $7.03 a Click-through rate: Here the click-through rate is calculated with click-throughs divided by impressions. bClick-throughs for a newspaper: In the case of the newspaper, the "click-through is considered the equivalent of calls into a call center (that is, a measurement of a potential customer seeking more information). Newspaper response rates vary widely due to the wide variety of items sold. Exhibit 3 MedNet Visitor Survey Resultsa Did you click on a sponsor's advertisement today? 3% Yes For those who clicked on the sponsor's advertisement, did you make a purchase? 6% Yes Have you clicked on a health advertisement at a search engine website? 1.4% Yes For those who clicked on a health advertisement at a search engine website, did you make a purchase? 2% Yes If you saw an advertisement on television or in a newspaper, would you call the call center? .74% Yes If you called about an advertisement on television or in a newspaper and found the information credible, would you make a purchase? 12% Yes Advertisers at MedNet are more likely to provide me with useful remedies and information than advertisers found on websites that don't adhere to the same evidence-based standards Strongly agree: 85% Strongly disagree: 15% How many health sites will you visit to research your condition? 85% = 3 or more How did you decide to go online to find health information on Med Net? 25% search engine 10% advertisement (print) 25% online advertisement 20% bookmarked this site 10% trusted advisor recommendation 10% e-mail letter from friend recommending an article Will you return to MedNet next time you need medical information? 93% Yes 7% No Would you allow MedNet to store personal information about your condition, such as blood pressure, weight, etc.? 40% Yes 60% No Would you pay for content at the MedNet site? 75% No Would you use MedNet if you had to register for some information? 50% No a The study's results, based on a very large sample size, also reflect general-health-website audience behavior. N=25,500 visitors Average Profit Margin per Pharmaceutical Prescription for Heart Medication Estimated contribution per sale $48 $45 Advertisement placement General interest website Search engine Health care website Newspaper (via call center) Television (via call center) $150 $165 $75 a This study measured the average advertising campaign contribution generated for the pharmaceutical when patients with chronic heart disease purchased a drug for long-term use. The medicine studied helped control high blood pressure. MedNet, most viewed pages, Nov. 2006 1. Search Page 2. Advanced medical search 3. Weight control center 4. Pharmaceutical news 5. Insurance news 6. Advanced pharmaceutical search 7. Health News Update 8. Controlling cholesterol 9. Depression center 10. Medical encyclopedia index page 11. Women's content index page 12. Allergy center 13. Prevention screening guide 14. Medical conditions table of contents page 15. Today in women's health 16. Today in children's health Audit of monthly usage and activity: 4.3 mm unique visitors Unique visitors not included in prior month's audit: 60% MedNet.com Confronts Click-Through Competition It was just 9:30 a.m., and the day was off to a terrible start. Heather Yates, vice president for business development at MedNet, walked at a quick clip down the hall of the company's modern Birmingham, Alabama, office space, her face clouded with concern. The company, a website delivering health information free to consumers, generated its income through advertising, mostly from pharmaceutical companies. Now, Windham Pharmaceuticals, MedNet's biggest advertiser, had asked to change the rules by which it had done business for the past four years. Moreover, Mahria Baker, Windham's CMO, had told Yates that this wasn't just an exploratory conversation. Windham was seriously considering shifting its MedNet ad dollars to Marvel, a competing website with which Windham already did some business. Yates, who had been with MedNet since just after the company was founded in 2002, felt blindsided and, at the same time, resigned. We have some legwork to do," she thought to herself. "We can't afford to say 'No,' and just walk away, and we can't just ask them to stay with us because we're good people. We have to convince them that our set-up is worth their ad dollars. And we have to move quickly. Our other advertisers won't be far behind Windham." She had asked Baker to fax over a copy of the results of Windham's latest advertising campaign, and had promised to call her back the next day, as both companies needed to finalize their budgets. Then, immediately after they had hung up, Yates had called Bill Bishop, MedNet's vice president of consumer marketing. "Can you clear some time for me right now?" she had asked him. "Windham is thinking of pulling their ad dollars from us and taking them to Marvel." Now she was on her way up to Bishop's office, two floors above, with the fax from Baker and notes from her conversation in hand. Industry Background and Company Origins MedNet had launched its website with three goals: to provide scientifically based medical information to a nonprofessional consumer audience; to provide this information for free; and to generate profits from advertising sales. In a year, it had met all the goals; by 2006, it generated $1 million in profits. (See Exhibit 1 for 2006 income statement.) The accessibly written, easy-to- navigate, and vividly presented content was developed by 24 trained journalists, doctors, designers, and administrators. Additional materials came from the faculty of a prominent medical school, news agencies, a photography service, and an active community of visitors that used social media tools such as blogs, community chat, and virtual reality to communicate medical information. (Visitor- generated media was reviewed by medically trained journalists.) The award-winning site was considered the best health website for trusted, evidence-based, consumer health information. Advertisements on MedNet proposed specific and immediate solutions to health concerns. MedNet had 4.3 million monthly visitors, but new competitors had flattened its audience growth during the last quarter of 2006. Competitors Now, in the first quarter of 2007, MedNet faced competition both for visitors and advertisers. Nonprofit and governmental websites competed with MedNet for visitors by providing similar content on mainstream medicine. The websites of the U.S. National Library of Medicine and World Health Organization weren't nearly as easy to navigate as MedNet, but they were comprehensive. In contrast to MedNet, these two websites provided information on alternative therapies as well as on scientifically based solutions, albeit with carefully worded disclaimers. What's more, employees of large corporations could increasingly turn to customized health websites on their own company intranets. The theory was that if internal health websites could help workers quickly identify health problems (prompting overdue doctor visits) and promote general good health, the employers could reduce their portion of employee health care costs. For-profit health websites posed different degrees of financial competition for MedNet's advertising revenue and audience. Recently, so-called condition-specific sites that focused on particular problems, such as Cholesterol.com, had emerged. (Yates was confident that Cholesterol.com was already drawing pharmaceutical advertising dollars away from MedNet.) An indirect competitor, ClinicalTrials.com, marketed only experimental procedures. Its audience was smaller than MedNet's and the material was difficult for the layperson to understand. ClinicalTrials.com received a fee for each time a visitor it referred enrolled in a clinical trial. Then there was Alternativehealth.com, a long-time, popular player in the "health space." It provided information about scientifically "unproven" therapies and procedures such as herbal remedies, vitamin regimens, and massage. Its audience was larger than MedNet's and its advertising sales more robust. Due to a recent lawsuit concerning its content, Alternativehealth.com had begun using disclaimerswith no apparent impact on its audience size. Due to the alternative health consumer's distrust of pharmaceutical companies, the website did not compete with MedNet for advertising dollars. Still, MedNet had to keep Alternativehealth on its radar. Methods Used to Calculate Advertiser Payment Yates's thoughts raced through the company's competitive landscape as she waited for the elevator. In her short phone conversation with Bill, he had told her to take a little time to review MedNet's original value proposition to its advertisers. What they needed to do was re-justify their approach, if it was possible to do so. But, he had cautioned, they were compelled to keep an open mind. "Think through the facts," Bill had said. "Why don't you come up here in about half an hour. I'll start to mull over our options as well." Yates thought back to MedNet's roots. Back in 2002, MedNet's founders had made some key choices regarding revenue generation. MedNet could, in theory, sell content to site visitors, like an online magazine, charging a few dollars per article or an annual subscription fee. On the other hand, if the site could draw advertisers, and if advertising revenues were strong enough, the company could provide content free of charge which is what most web users expected. An advertising revenue model was made possible by sophisticated web analytics: technology that tracked the behavior of each site visitor-pages viewed, links clicked, and so on. This software made it easy for advertisers to calculate their return on advertising investment (ROI). The obvious candidates to buy onscreen advertising space from MedNet were pharmaceutical companies, which for over a decade had promoted their drugs aggressively to consumers. As it happened, MedNet was launched at a time when many other consumer health care websites were going out of business, leaving pharmaceutical firms looking for web promotion outlets. MedNet seized the opportunity to build relationships with these advertisers. In deciding how best to generate revenue from advertisers, MedNet chose traditional banner advertising, charging pharmaceutical advertisers such as Windham Pharmaceuticals on a cost-per- thousand impressions (CPM) basis. (One advertising impression meant that one visitor requested from a Web server a page that had a specific advertisement on it.) Measuring impressions was the closest way to estimate the number of people who actually saw an online advertisement. By pursuing an impression business model, MedNet was fully "monetizing" its available inventory of eyeballs (site visitors). An independent auditor verified the company's impression counts each month. Marvel's Challenge Yates reached Bill Bishop's office and pushed the door open. Bill was on the phone, but he waved her to a seat. Two minutes," he mouthed at her. She nodded, and sat back. She thought about what she knew about Marvel. Marvel was essentially a large search engine that had decided to follow the alternative advertising model: contextual, or pay-per-click, banner advertising. Under these terms, advertisers paid website owners only when visitors actually clicked" on an advertisement to learn more about an advertised product. The key metric to measuring this kind of online advertising campaign was the click-through rate (CTR), measured as the number of clicks divided by the number of ad impressions delivered. Advertisers considered website click-throughs (and telephone calls to a call center generated by a newspaper advertisement) to be the equivalent of customers interested in potentially making a purchase. Yates thought back to 2002. No sooner had MedNet's founders opted for a pay-per-impression model than advertisers began resisting that pricing structure but mainly from general-interest websites, where the majority of impressions came from visitors uninterested in their products. Advertisers based this perception in part on the percentage of click-throughs that ads yielded; the click-through rate on a general-interest site tended to be half as high as on highly focused "destination" content sites like MedNet. In 2006, MedNet.com therefore could still command a $100 CPM ($100 for each 1,000 impressions) contract from its advertisers10 to 20 times what genera interest websites might charge. Similarly, Alternativehealth.com's advertisers paid for impressions only, and not for click-throughs. But Marvel, a hugely successful search engine, turned the table on its competition in the fall of 2006 by declaring it would provide impressions for free and charge advertisers only for click- throughs. Because Marvel had a vast audience (19 million visitors per month), charging for even a small percentage of click-throughs would pay off handsomely. If the site sold advertisements in enough categories, including the pharmaceutical market, Marvel could bring in huge revenues. By late 2006, some advertisers began to ask other sites to charge only for click-through sales leads like Marvel did. One drawback to this popular revenue model: reports of increasing "click fraud." Advertisers' competitors were fraudulently clicking on advertisements to drive up advertising costs. Not only was Marvel offering MedNet's long-standing advertisers like Windham different financial terms, but it also competed for visitors interested in healthcare. Visitors often came to MedNet by way of a search engine such as Marvel, although such search engines served as a starting point of inquiry, not a serious source of trusted medical information. Mahria Baker's challenge stuck with Yates: "At Marvel we get all our impressions for free, and we pay $0.54 for each click-through. At MedNet we pay for every impression, and by my calculation we pay $3.33 for each click-through. Granted, we're not averse to getting impressions anytime that anyone sees your logo, your slogan, and your product's name, you are theoretically doing your brand some good. But here at Windham, click-throughs are really what matter. They separate accidental observers of our ads from the serious prospects who proactively seek more product information and may buy our product. I can't justify paying six times as much for a click-through from one of your visitors." Baker had paused a moment, then added, Heather, help me here. Is there another way of looking at this that I'm missing?" Yes, there is," Yates had replied, and if you let me call you back tomorrow I believe I can show you what you are missing." MedNet's Audience and Visitor Behavior Bill Bishop hung up the phone and turned to Yates. She spread out a copy of the results of Windham's latest advertising campaign, and the two of them pored over it. (See Exhibit 2 for Baker's data.) Many search engines and general-interest websites had large audiences that returned to the sites regularly, in a predictable pattern. By contrast, most visitors to targeted health websites such as MedNet came only when "in crisis. However, when they did come, they stayed long and explored avidly, clicking around to clarify symptoms or determine the best course of action for a pressing health problem. They often researched unrelated symptom areas as well, in order to help family members, or out of curiosity. These visitors then returned during the next crisis, although some did become repeat visitors. MedNet visitors clicked on more pages and advertisements than general- interest web surfers did (see Exhibit 3). In addition, health website visitors tended to buy more products from advertisers when they did decide to purchase. (See Exhibit 4 for a study of results and frequently viewed web pages on MedNet.) If the product advertised was not available over-the- counter, then the visitors would urge their physicians to prescribe the medication that they'd discovered in the advertisements on MedNet. Windham produced Vesselia, a prescription medication that reduced cholesterol and plaque in a patient's veins with fewer side effects than competitors' offerings. High cholesterol was one cause of heart disease, and it was attributed to both genetic predisposition and lifestyle choices. Keeping cholesterol low could be a long-term issue for many patients, requiring months, possibly years, of daily medication. Each patient who began a series of treatments would use the medicine for an average of 12 months. To encourage customers to request a prescription for Vesselia from their doctors, Windham provided coupons on its website that customers could print out and redeem at a pharmacy. Printed on each coupon was a bar code that included information identifying the referring advertisement. For instance, when a customer clicked on a Windham ad at MedNet's website, he was taken to the Windham website. Windham's computer system could identify that the customer came from MedNet and insert that information into the Windham coupon bar code within fractions of a second. A different coupon code was provided to those web visitors who came to Windham from Marvel Search. (Coupons with yet another barcode were sent by postal mail by the Windham telephone call center to respondents to newspaper advertisements.) When patients redeemed the coupons at a pharmacy, the pharmacy returned them to Windham. Windham could thus attribute drug sales to the relevant advertising venue. On average, patients took three months to redeem coupons for Vesselia after Windham had first placed the advertisements. The current campaign would be considered closed at the end of February 2007. MedNet Discusses the Marvel Threat Bill looked up from the report, turned to his computer screen, then to Yates. So what you're saying is that Windham wants to pay only for click-throughs, and that you think Windham is just the tip of the iceberg. But you and I have done the math on this issue many times. If we sell only click- throughs at a rate that competes with Marvel, our revenues drop at least 80% if our audience size remains where it is." Yates knew that Bill wasn't going to like what she was about to say, but she didn't pause. "If we could increase the size of our audience," she said, "we'd have more click-throughs to sell." Bishop had started shaking his head as soon as Yates had started to speak. The quickest way to a bigger audience is to extend our coverage to alternative healing approaches. But our board would have a hard time with that." Bishop was mindful of the two eminent physicians on MedNet's board of directors who consistently blocked proposals to deliver content about, and ads for, herbal remedies. Yates sighed. "I understand their concern, but aren't some explanations of alternative approaches acceptable? Could we have a reference encyclopedia of alternative medicine that doesn't discuss its claims, just the plants involved? Or focus on more generally accepted practices like chiropractic medicine and acupuncture?" Bishop shook his head again. "We can't get advertising growth from that group. I don't think the alternative health audience will click on a pharmaceutical advertisement. Most of them don't trust pharmaceutical companies or Western medicine." The two were silent for a few moments. At length, Bishop looked up. "What about, instead of selling click-throughs, we contract with large employers to become a corporate health site of record? If we made our money from corporations, we could reduce our reliance on advertisers like Windham." It was Yates's turn to remember the board's admonition: independence. "It could solve a corporation's problems regarding employee health record privacy. But we would then be involved in a debate about driving health care costs down. That could hurt our main business. Plus, we'd be inviting the perception-right or wrongthat we'd abandoned our hard-nosed scientific independence in morphing from an information content business to a human resources service- provider-for-hire." Yates exhaled sharply and looked down at the fax from Baker. "You and I both know there are no easy long-term solutions to the new competitive challenges or our need to grow the business. But we do have a short-term problem to solve we have to get Windham to recognize that we're a great solution for them. One worrisome fact is that Baker underestimates the genuine value that our impressions deliver to an advertiser. Visitors to MedNet see those ads in the context of a trusted and helpful site-a neighborhood of family friends, reallyand even if they don't buy right away, they are left with a positive impression of the advertiser and its products." "Agreed," said Bishop. "But factors like trust are hard to measure in dollars. And if I know Baker, the only way to win this argument is with numbers, not intuition. So let's compare the numbers that MedNet generates on an impression basis with the numbers that Marvel generates but let's take the analysis further than just the cost of one click-through. Our audience is fundamentally different from Marvel's, and maybe that difference can be quantified. Let's try." A Problem Solved? Bishop and Yates got Mahria Baker on speakerphone late that afternoon. "Hello, Bill," said Baker. I wasn't expecting to hear from you until tomorrow. Does this mean that you've convinced Heather to sell me results like Marvel does?" "We're all about results, and you know that," said Bishop, looking at Yates. "Our click-throughs are twice as strong as Marvel's." Then just sell me those click-throughs," said Baker. "I'd even double the price_$1 per click- through." I think that you're overpaying for clicks from Marvel," said Yates. "This I've got to hear," Baker replied. Yates looked at the analysis that she and Bishop had completed just an hour before. Combining MedNet's own data with information from Windham's advertising campaign that Baker had provided in her fax, Yates and Bishop had built a compelling numbers-based case that Windham was getting better value from MedNet than from Marvel. "You're getting a lot more from MedNet's audience than Marvel gives you," said Yates. "Your ads appear on a page with trusted medical information, our audience is attracted to your products, and we have reason to believe that our advertising partnership adds to your bottom line." "Mahria," Bishop jumped in, "Marvel has provided click-throughs. But those are just opportunities to get your information in front of a person, not actual sales. What's a click-through worth if it produces no sale? We believe that the Marvel audience is not nearly as lucrative to Windham as the audience we provide. When all of the Vesselia promotional coupons are returned to you, Windham will see that MedNet delivered the best sales results." How about if we don't bill you until the end of February?" asked Yates. "You'll be able to see what coupons have been redeemed and realize that this is a great deal. Would that work?" Early that afternoon, MedNet's CFO had agreed to let her make the offer to promote good relations with a long- time customer. "That helps," said Baker slowly. "I'll listen to your case." Yates carefully laid out the math behind her and Bishop's analysis. At the end, Baker was silent for what seemed to Yates like an hour. Then Baker said, "I've got to admit, your case seems solid. I want my numbers whiz to confirm my reading of this, but if he does, I'd say we're going to have to agree with you about the value we are getting from MedNet. Would you fax over that study about heart medication profit margins? I'd like to see what it says about audience behavior influencing those margins." "Sure," said Yates, smiling for the first time that day. She was relieved that she'd apparently won this fight for MedNet, and now she wanted to leave Baker with a strong closing statement. "It all comes down to what Windham wants. If you just want people to click on your ads at a low price rate, a search engine like Marvel can give you that. But if you want people to see the ads when they're psychologically disposed to actually look at the content and consider their message, you want MedNet. And if you want sales that end up generating a profit, you also want MedNet." Baker said, "Interesting you put it that way, Heather. You've just introduced another problem that we might as well begin tackling right now." Yates and Bishop looked at one another. MedNet Confronts the Competition, Round 2 Baker continued. In arguing this case for MedNet, you've inadvertently made a case for Cholesterol.com as well. They have the same strengths you just attributed to MedNet-maybe more as far as Vesselia is concerned. My ad budget's not growing, and now I have to use some of it to pay for ads on Cholesterol.com. If I'm not on that site, my competitors will get those customers. So even if you've made your case about the click-throughs, I still need some fresh angles on how your site sells Vesselia in ways that a Cholesterol.com cannot." Yates stared at the phone. Then she looked over at Bill, who was tilting his head back, his eyes closed, and his lips pressed shut. How would they respond to this one? She recognized Baker's point. Both MedNet and Cholesterol.com had targeted, high-profit audiences that returned for up-to-date and trustworthy solutions about cholesterol medication. Yates knew that she and Bishop had made a great case for Baker to move away from Marvel. But could she persuade this tough-minded advertiser to bypass Cholesterol.com in favor of MedNet? The new group of niche, condition-specific competitors like Cholesterol.com were "category- killer" sites typically focused on one (profitable) chronic condition such as cardiovascular disease, depression, or obesity, and sought to disseminate the latest information from medical sources. In addition, these sites often provided interactive tools on which visitors could store data they wished to track, such as blood pressure, weight, or cholesterol counts. While the income sources were limited, their pull on the newly diagnosed was incontrovertible. Pharmaceutical firms that had relevant medications rushed to buy ads on these sites, which were quickly becoming the first web resource that "core constituencies" routinely visited. A wealthy trial lawyer had recently launched Cholesterol.com with $47 million he had been awarded in a class-action lawsuit against a fast-food restaurant chain. The lawyer assembled an international staff of doctors who explained what most large countries provided in chronic cholesterol care, presenting the information in 13 languages, including Chinese. Significantly, Cholesterol.com tailored health recommendations to each visitor's specifications and even offered a travel agency service to promote "global health tourism." Pharmaceutical companies from around the world advertised their offerings on that site, and, according to third-party web traffic audits, Cholesterol.com's niche audience was growing, especially in Asia. The site's significant marketing budget paid for a large, multilanguage advertisement campaign. Even in the face of this specialized niche competition, MedNet's executive leadership continued to believe that providing a source of information on a wide range of medical conditions delivered real value to its readers. MedNet's audience-auditing firm showed a majority of visitors clicked on both condition-specific pages and general health information. MedNet board members also perceived that some condition-specific sites came dangerously close to diagnosing conditions and prescribing treatments for their visitors, and thus were at risk of violating both state and federal government regulations (and the laws of many foreign nations) that required medical advice to be dispensed in person by a licensed physician. As a result, MedNet's board refused to provide tailored recommendations about medical treatment. That said, here were Yates and Bishop in a conference call with their biggest advertiser, who was saying she couldn't afford not to divert advertising dollars from MedNet (as well as other ad venues) to Cholesterol.com. The pair felt they'd successfully answered the Marvel challenge only to confront this new threat. How would they respond to Mahria Baker? And what about the bigger picture? How could they reinvigorate MedNet's growth when they were being hit by new competitive challenges that they were blocked, in one way or another, from taking on headfirst? "Mahria, we're going to need a little time on this one," Yates said, finally. "We're sure that we can convince you that MedNet is your best bet, but we don't want to answer on the fly. I'm sure you don't want us to do that either. Let us get the facts in front of us, as we've done with regard to Marvel, and call you tomorrow morning." Better yet, would your schedules allow a meeting?" Baker asked. It would be good to sit down together, don't you think?" Yates and Bishop exchanged glances, and agreed to meet Baker the following morning at the Windham offices. Then they ended the call. Bishop puffed out his cheeks and blew out a sigh of exasperation. "How late can you stay this evening?" he asked. "We can't let this one wait. And let me see if any of the other senior crew is here." *** Much later that evening, Bishop and Yates, joined now by MedNet's president and CEO Frank D'Onofrio and the company's CFO, Bradley Meyers, considered possible responses to Baker-and possible scenarios for MedNet's future. Among the options they had scrawled on the white board: Take a more prescriptive, diagnostic posture toward site visitors treating them, as Cholesterol.com did, almost as patients. Then they could charge for content and be less dependent on advertising revenues. But would MedNet's board stand for this more aggressive approach to dispensing medical information? Bring alternative health information to the site, starting conservatively (perhaps with scientific studies of acupuncture) and slowly becoming more liberal. But would this help the problem of flattening advertising revenues from pharmaceutical firms like Windham? Build on their greatest strengththeir integrity and trustworthinessas well as their web business expertise, to evolve into a developer and manager of employer websites. But would employers let them introduce pharmaceutical advertising? If not, wouldn't they still lose in the long run? Exhibit 1 MedNet Income Statement, 2006 Revenue Advertising income $ 12,000,000 12,000,000 Expenses Purchased content Sales and marketing Technology support General administration 3,700,000 3,000,000 1,300,000 3,000,000 11,000,000 $ 1,000,000 Net income Cost per Impressions Windham received Monthly visitors Click- through ratea Cost Total ad costs Advertising venue MedNet Click-throughs 516,000 click-through $3.33 4.3 mm/month 17.2 mm $100 CPM 3% $1.72 mm Marvel Search 19 mm/month 57 mm 1.4% $430,920 $.54 $.54 per click-through $260,000/2-day ad 798,000 37,000b U.S. Newspaper 2.5 mm/day 5 mm .74% $