Regardless of your prior answers, in answering the below questions, assume the independence of both Jack Jones and ABC LLP were impaired.

- Based on the information in the above case, to what sanctions or penalties do you think Jack Jones should besubjected?

- Based on the information in the above case, to what sanctions or penalties do you think the ABC accounting firm should be subjected?

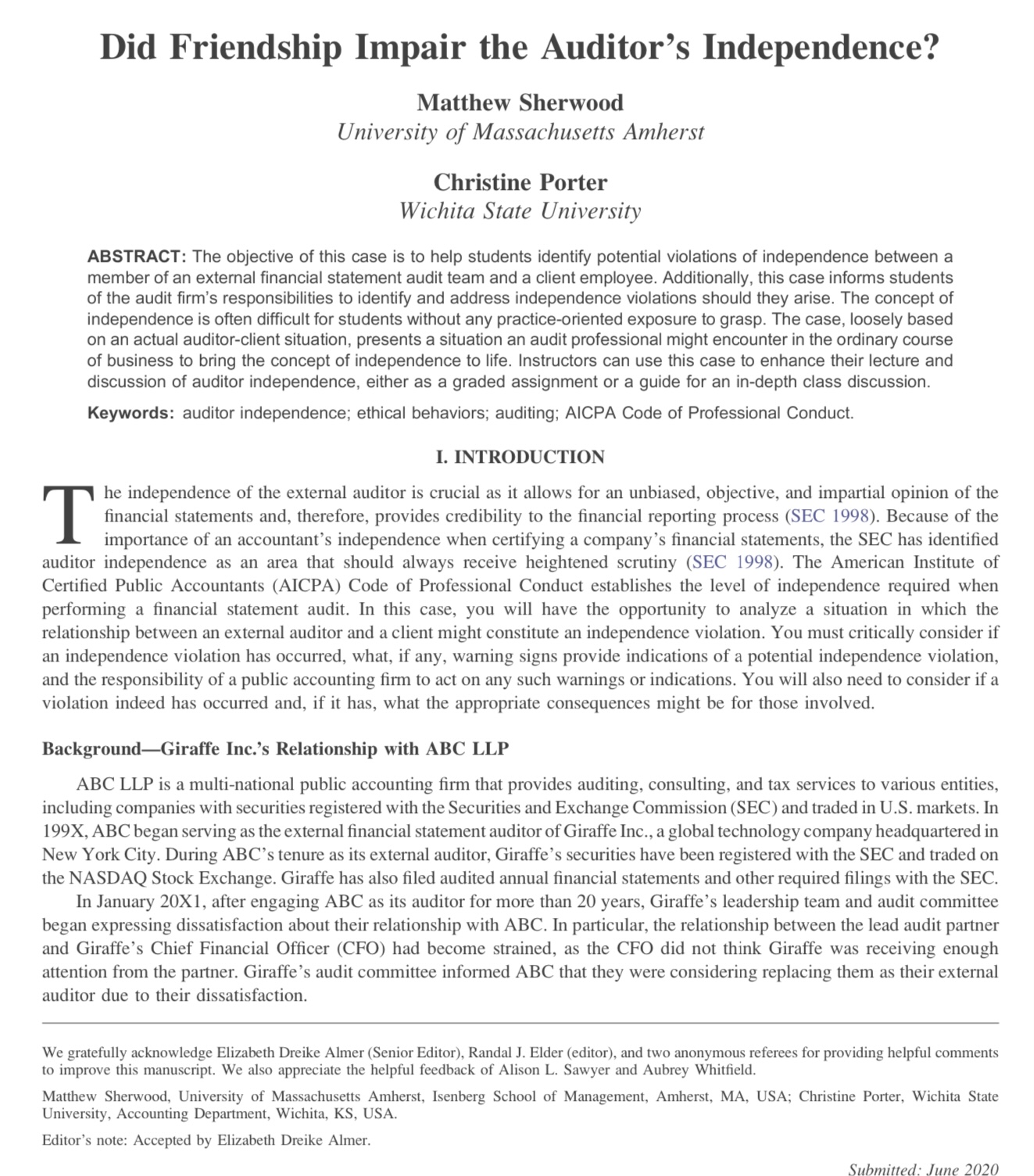

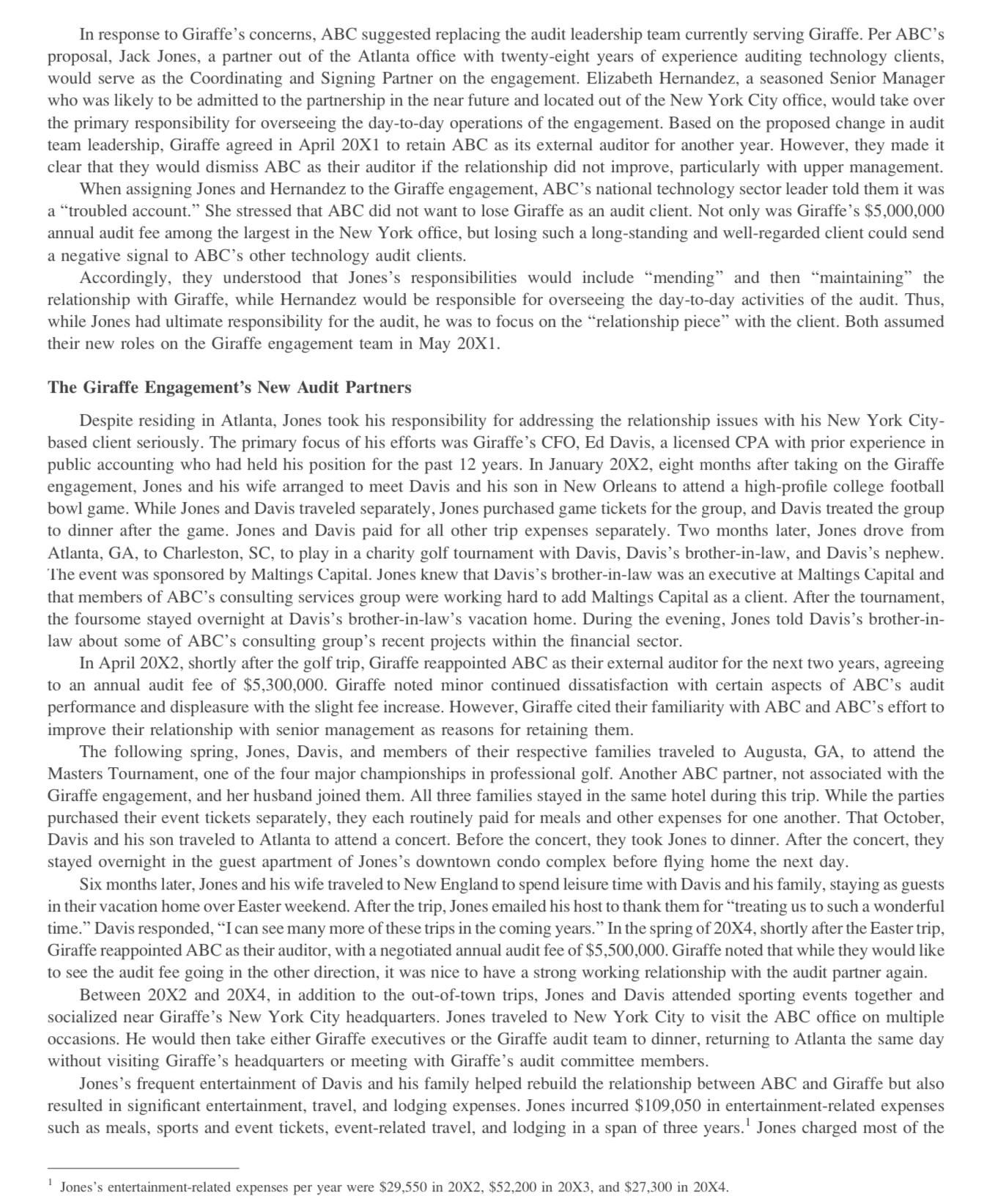

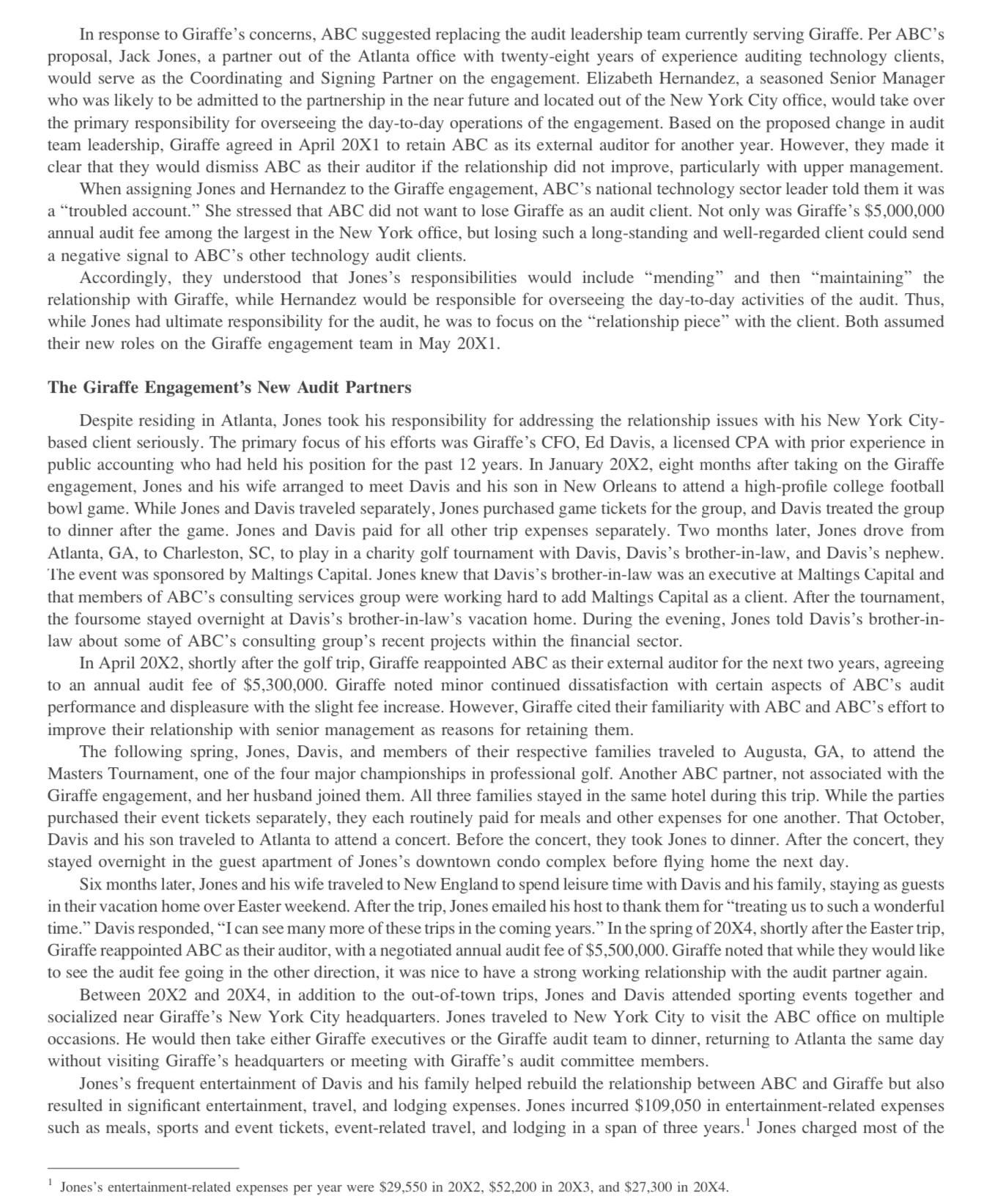

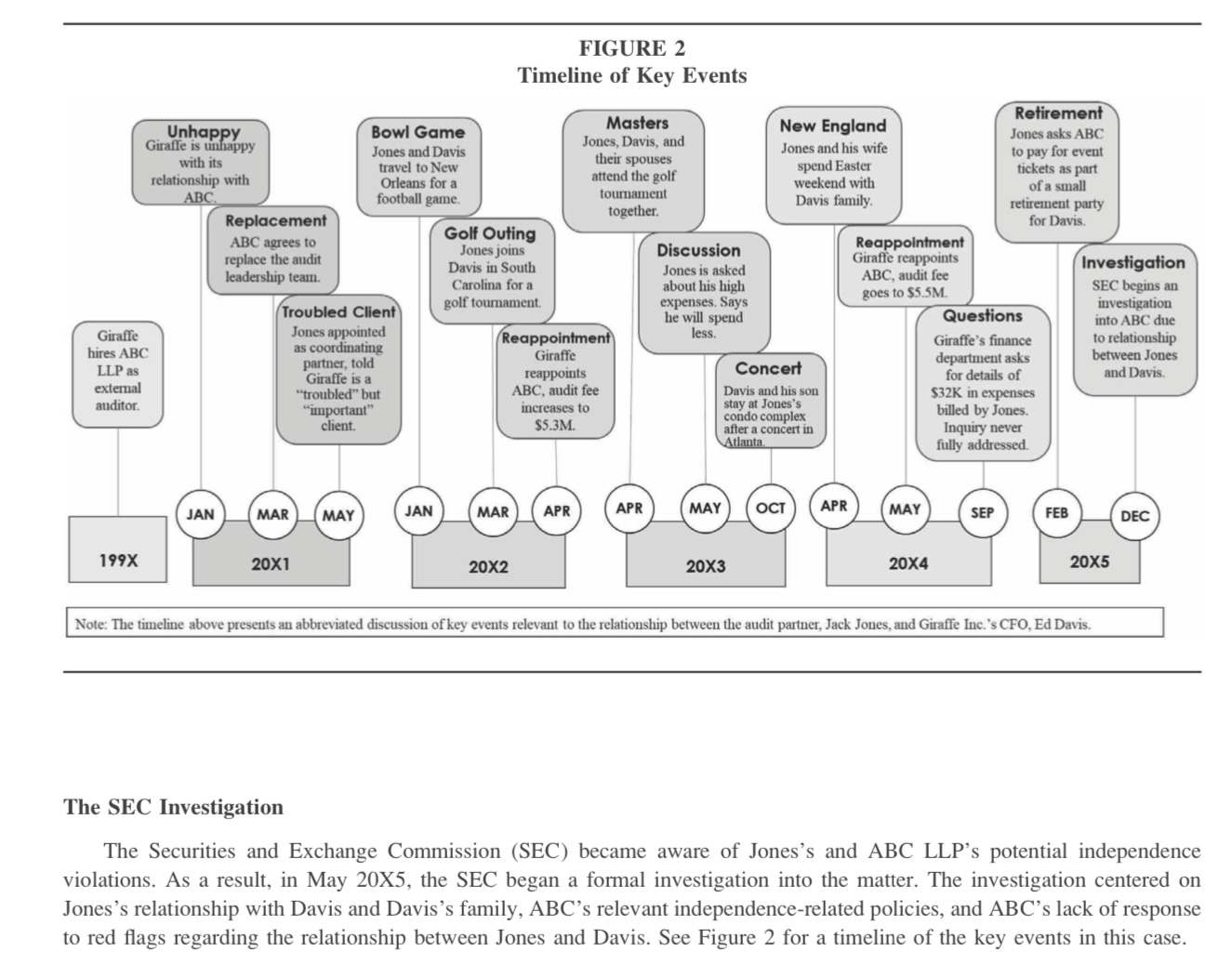

Did Friendship Impair the Auditor's Independence? Matthew Sherwood University of Massachusetts Amherst Christine Porter Wichita State University ABSTRACT: The objective of this case is to help students identify potential violations of independence between a member of an external financial statement audit team and a client employee. Additionally, this case informs students of the audit firm's responsibilities to identify and address independence violations should they arise. The concept of independence is often difficult for students without any practice-oriented exposure to grasp. The case, loosely based on an actual auditor-client situation, presents a situation an audit professional might encounter in the ordinary course of business to bring the concept of independence to life. Instructors can use this case to enhance their lecture and discussion of auditor independence, either as a graded assignment or a guide for an in-depth class discussion. Keywords: auditor independence; ethical behaviors; auditing; AICPA Code of Professional Conduct. I. INTRODUCTION he independence of the external auditor is crucial as it allows for an unbiased, objective, and impartial opinion of the financial statements and, therefore, provides credibility to the financial reporting process (SEC 1998). Because of the importance of an accountant's independence when certifying a company's financial statements, the SEC has identified auditor independence as an area that should always receive heightened scrutiny (SEC 1998). The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Code of Professional Conduct establishes the level of independence required when performing a financial statement audit. In this case, you will have the opportunity to analyze a situation in which the relationship between an external auditor and a client might constitute an independence violation. You must critically consider if an independence violation has occurred, what, if any, warning signs provide indications of a potential independence violation, and the responsibility of a public accounting firm to act on any such warnings or indications. You will also need to consider if a violation indeed has occurred and, if it has, what the appropriate consequences might be for those involved. Background-Giraffe Inc.'s Relationship with ABC LLP ABC LLP is a multi-national public accounting firm that provides auditing, consulting, and tax services to various entities, including companies with securities registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and traded in U.S. markets. In 199X, ABC began serving as the external financial statement auditor of Giraffe Inc., a global technology company headquartered in New York City. During ABC's tenure as its external auditor, Giraffe's securities have been registered with the SEC and traded on the NASDAQ Stock Exchange. Giraffe has also filed audited annual financial statements and other required filings with the SEC. In January 20X1, after engaging ABC as its auditor for more than 20 years, Giraffe's leadership team and audit committee began expressing dissatisfaction about their relationship with ABC. In particular, the relationship between the lead audit partner and Giraffe's Chief Financial Officer (CFO) had become strained, as the CFO did not think Giraffe was receiving enough attention from the partner. Giraffe's audit committee informed ABC that they were considering replacing them as their external auditor due to their dissatisfaction. We gratefully acknowledge Elizabeth Dreike Almer (Senior Editor), Randal J. Elder (editor), and two anonymous referees for providing helpful comments to improve this manuscript. We also appreciate the helpful feedback of Alison L. Sawyer and Aubrey Whitfield. Matthew Sherwood, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Isenberg School of Management, Amherst, MA, USA; Christine Porter, Wichita State University, Accounting Department, Wichita, KS, USA. Editor's note: Accepted by Elizabeth Dreike Almer. In response to Giraffe's concerns, ABC suggested replacing the audit leadership team currently serving Giraffe. Per ABC's proposal, Jack Jones, a partner out of the Atlanta office with twenty-eight years of experience auditing technology clients, would serve as the Coordinating and Signing Partner on the engagement. Elizabeth Hernandez, a seasoned Senior Manager who was likely to be admitted to the partnership in the near future and located out of the New York City office, would take over the primary responsibility for overseeing the day-to-day operations of the engagement. Based on the proposed change in audit team leadership, Giraffe agreed in April 20X1 to retain ABC as its external auditor for another year. However, they made it clear that they would dismiss ABC as their auditor if the relationship did not improve, particularly with upper management. When assigning Jones and Hernandez to the Giraffe engagement, ABC's national technology sector leader told them it was a "troubled account." She stressed that ABC did not want to lose Giraffe as an audit client. Not only was Giraffe's $5,000,000 annual audit fee among the largest in the New York office, but losing such a long-standing and well-regarded client could send a negative signal to ABC's other technology audit clients. Accordingly, they understood that Jones's responsibilities would include "mending" and then "maintaining" the relationship with Giraffe, while Hernandez would be responsible for overseeing the day-to-day activities of the audit. Thus, while Jones had ultimate responsibility for the audit, he was to focus on the "relationship piece" with the client. Both assumed their new roles on the Giraffe engagement team in May 20X1. The Giraffe Engagement's New Audit Partners Despite residing in Atlanta, Jones took his responsibility for addressing the relationship issues with his New York Citybased client seriously. The primary focus of his efforts was Giraffe's CFO, Ed Davis, a licensed CPA with prior experience in public accounting who had held his position for the past 12 years. In January 20X2, eight months after taking on the Giraffe engagement, Jones and his wife arranged to meet Davis and his son in New Orleans to attend a high-profile college football bowl game. While Jones and Davis traveled separately, Jones purchased game tickets for the group, and Davis treated the group to dinner after the game. Jones and Davis paid for all other trip expenses separately. Two months later, Jones drove from Atlanta, GA, to Charleston, SC, to play in a charity golf tournament with Davis, Davis's brother-in-law, and Davis's nephew. 'The event was sponsored by Maltings Capital. Jones knew that Davis's brother-in-law was an executive at Maltings Capital and that members of ABC's consulting services group were working hard to add Maltings Capital as a client. After the tournament, the foursome stayed overnight at Davis's brother-in-law's vacation home. During the evening, Jones told Davis's brother-inlaw about some of ABC's consulting group's recent projects within the financial sector. In April 20X2, shortly after the golf trip, Giraffe reappointed ABC as their external auditor for the next two years, agreeing to an annual audit fee of $5,300,000. Giraffe noted minor continued dissatisfaction with certain aspects of ABC 's audit performance and displeasure with the slight fee increase. However, Giraffe cited their familiarity with ABC and ABC's effort to improve their relationship with senior management as reasons for retaining them. The following spring, Jones, Davis, and members of their respective families traveled to Augusta, GA, to attend the Masters Tournament, one of the four major championships in professional golf. Another ABC partner, not associated with the Giraffe engagement, and her husband joined them. All three families stayed in the same hotel during this trip. While the parties purchased their event tickets separately, they each routinely paid for meals and other expenses for one another. That October, Davis and his son traveled to Atlanta to attend a concert. Before the concert, they took Jones to dinner. After the concert, they stayed overnight in the guest apartment of Jones's downtown condo complex before flying home the next day. Six months later, Jones and his wife traveled to New England to spend leisure time with Davis and his family, staying as guests in their vacation home over Easter weekend. After the trip, Jones emailed his host to thank them for "treating us to such a wonderful time." Davis responded, "I can see many more of these trips in the coming years." In the spring of 20X4, shortly after the Easter trip, Giraffe reappointed ABC as their auditor, with a negotiated annual audit fee of $5,500,000. Giraffe noted that while they would like to see the audit fee going in the other direction, it was nice to have a strong working relationship with the audit partner again. Between 20X2 and 20X4, in addition to the out-of-town trips, Jones and Davis attended sporting events together and socialized near Giraffe's New York City headquarters. Jones traveled to New York City to visit the ABC office on multiple occasions. He would then take either Giraffe executives or the Giraffe audit team to dinner, returning to Atlanta the same day without visiting Giraffe's headquarters or meeting with Giraffe's audit committee members. Jones's frequent entertainment of Davis and his family helped rebuild the relationship between ABC and Giraffe but also resulted in significant entertainment, travel, and lodging expenses. Jones incurred $109,050 in entertainment-related expenses such as meals, sports and event tickets, event-related travel, and lodging in a span of three years. 1 Jones charged most of the 1 Jones's entertainment-related expenses per year were $29,550 in 20X2,$52,200 in 20X3, and $27,300 in 20X4. Did Friendship Impair the Auditor's Independence? 123 entertainment-related expenses described above to a billable time code associated with the Giraffe audit engagement, resulting in most of these entertainment-related expenses being billed to and paid by Giraffe as audit expenses. ABC's Employee Independence and Hospitality and Gifts Policies At all times between 20X1 and 20X5, ABC's Office of Ethics and Compliance maintained policies concerning employees' independence from a public audit client, reimbursement for client-related expenses, and reimbursement for non-business entertainment and gifts. Annually, all ABC professionals received copies of these policies. Employees were required to complete an online self-study training on these policies and submit an annual independence certification form. The Office of Ethics and Compliance also maintained an anonymous tips hotline to allow employees to report possible illegal, unethical, or improper conduct when the normal communication channels had proven ineffective, or employees feared negative repercussions from reporting. The Hospitality and Gifts Global Policy (HGGP) ABC had in place between 20X1 and 20X5 required, among other things, that all hospitality events involving clients have a valid business purpose. According to the HGGP, a valid business purpose meant that during the activity/event, there would be a meaningful business discussion or professional purpose. The HGGP also indicated that in the rare instances where a hospitality activity/event was of a purely social nature, such as hosting an end-ofengagement dinner for client employees and members of the engagement team, a proportionally significant number of relevant client personnel be present. While the HGGP policy did allow ABC employees to give (receive) gifts to (from) employees of their clients, such gifts were to be of a reasonable monetary value, and exchanges were to occur on an infrequent and irregular basis. Any entertainment-related spending that was more than a reasonable amount was to be approved before occurrence. The HGGP also specified that employees were to charge non-business-related gifts, hospitality, and entertainment expenses to nonbillable internal charge codes, not billable client charge codes. Jones completed the HGGP training annually, confirming that he was compliant with the policy. In addition to the HGGP, ABC also had an Employee Independence Policy (EIP) in place between 20X1 and 20X5. Among other things, the EIP required employees to obtain approval from the firm before performing any concurrent employment with a client and approval from an audit client's Board of Directors before performing any non-audit services for an audit client. The policy acknowledged that a close personal relationship between a member of an audit engagement team and an employee of an audit client might create an independence issue, especially between members of the engagement leadership team and employees with accounting or financial reporting oversight responsibilities. As a result, in addition to prohibiting romantic relationships, the policy also prohibited audit partners from taking non-business-related trips with executive-level audit client employees. The policy also encouraged audit partners to limit the amount of leisure time they spent with audit client employees having accounting or financial reporting oversight responsibilities. The firm required engagement team members to certify their independence from their audit clients annually via an independence certification form. While the firm's independence policy recognized that personal relationships could cause an independence issue, the independence certification form did not specifically ask about such relationships. Instead, independence certification forms expressly asked about (a) ownership or other business dealings with audit clients, (b) concurrent employment contracts between the ABC employee and audit clients, and (c) the performance of any unauthorized non-audit services for audit clients. Jones completed the independence certification forms every year, noting his compliance with the EIP. Jones did not attempt to hide his friendship with Davis. As a result, multiple members of the Giraffe audit engagement team, including Hernandez, were aware of at least four overnight, out-of-town trips that Jones and Davis had taken together. ABC's audit teams found no evidence that Giraffe's financial statements contained material misstatements during any of the years that ABC served as their external auditor. As a result, ABC issued a clean audit opinion each year. Monitoring and Oversight The significant size of Jones's entertainment-related expenses did not go unnoticed by ABC leadership. In May 20X3, Jones sought the help of Howard Smith, the Office Managing Partner of ABC's Atlanta office, and Maggie Bosworth, the national partner over ABC's Technology Sector Audit Services Group, when his reimbursement request for spousal travel, unrelated to the Giraffe engagement, was denied. Upon inquiring on his behalf with the firm's national time and expense office as to the reason for the denial, Smith and Bosworth were informed that Jones's non-business expense spending for the past year was by far the highest in the practice. This prompted Smith to try and better understand Jones's spending and how it might impact the practice. See Figure 1 for a review of the key individuals involved in the case. Upon further investigation, Smith learned that Jones's total expense spending between January and April of that year had been $80,359, with $31,852 of that for "entertainment" associated with several clients, including Giraffe. He also learned that not only were Jones's expenses the largest of anyone in the firm's audit line of service, but they were also more than double that FIGURE 1 Kev Plavers Note: The individuals shown above are the primary participants within this case study. of the next closest person. Smith informed Bosworth of this, and the two of them spoke to Jones via video conference about his controllable expenses. When confronted, Jones claimed that the large volume of expenses was due partly to the fact that he was catching up on submitting older expenses but that he would do better with his spending going forward. Neither Bosworth nor Smith inquired into the nature of Jones's expenses or if the significant non-business expenses might be due to an inappropriate personal relationship that could be impairing his independence. The client noticed the level of Jones's spending as well. In September 20X4, a senior member of Giraffe's finance department asked the ABC engagement team for more detail on the expenses ABC was billing Giraffe. The engagement team provided a four-line expense summary table, showing the amount billed divided into three sub-categories: transportation, lodging, and meals. Upon receipt, the Giraffe employee responded that the table was too summarized and requested one showing the expenses incurred by each engagement team member. Hernandez then reviewed the expense spending, noting that between January and August 20X4, Jones had billed Giraffe for $32,000 in expenses, of which $18,000 were entertainment expenses. Per Jones's instructions, Hernandez reclassified the entertainment expenses as meal expenses and then provided a summarized total of expenses per engagement team member across the same three categories: transportation, meals, and lodging to the Giraffe employee. The Giraffe employee responded, copying Jones on the email, with five questions about the expenses, one of which was, "Mr. Jones has $32K in expenses this year. That seems high, given he has only been to our headquarters a few times this year. What is in here?" Neither Hernandez nor Jones ever responded to the request for additional details. In February 20X5, Jones invited eight people to join him and his wife in Augusta, GA, that April to attend the Masters Tournament and celebrate Davis's upcoming retirement. In addition to Davis and his wife, Jones invited Hernandez and her husband, two ABC audit partners not affiliated with the Giraffe audit, and two senior-level employees from one of his other audit engagements. Jones informed them that he would provide housing and tickets to the tournament's opening round as this was a "business" meeting. A week later, Jones sent emails to Bosworth and Smith describing the trip as a client networkbuilding event, noting it would be an excellent opportunity for Hernandez to expand her network. He informed them of his plan to provide housing for the group and asked if ABC would pay for tickets to the tournament. He noted that he didn't want to create an issue if this might raise some eyebrows. Bosworth and Smith each responded that ABC would not be able to pay for the tickets. However, Bosworth did thank Jones for his continued focus on building long-lasting client relationships on ABC's behalf and his efforts to mentor Hernandez. Neither Bosworth nor Smith questioned Jones about the legitimacy of this being a business trip or that he was planning to share a housing rental with three executive-level audit client employees. The SEC Investigation The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) became aware of Jones's and ABC LLP's potential independence violations. As a result, in May 20X5, the SEC began a formal investigation into the matter. The investigation centered on Jones's relationship with Davis and Davis's family, ABC's relevant independence-related policies, and ABC's lack of response to red flags regarding the relationship between Jones and Davis. See Figure 2 for a timeline of the key events in this case