Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

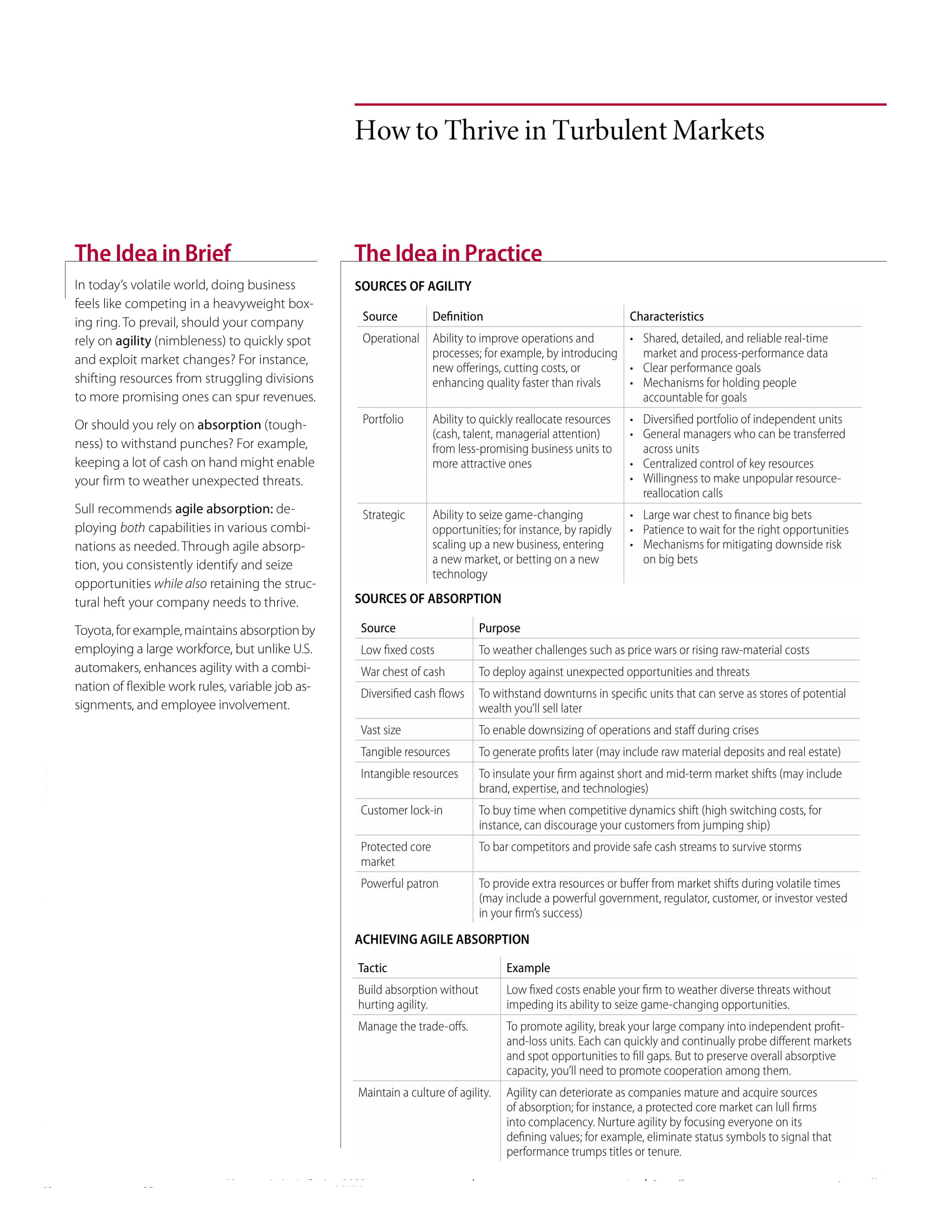

summary for this article :key theme, major findings, and key implications Harvard Business Review www.hbr.org A classic boxing match offers useful lessons for seizing How

summary for this article :key theme, major findings, and key implications

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started