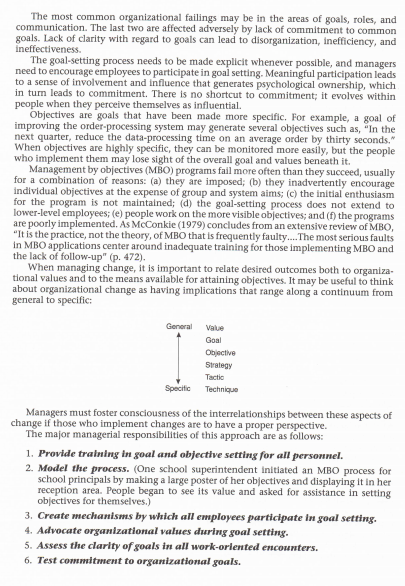

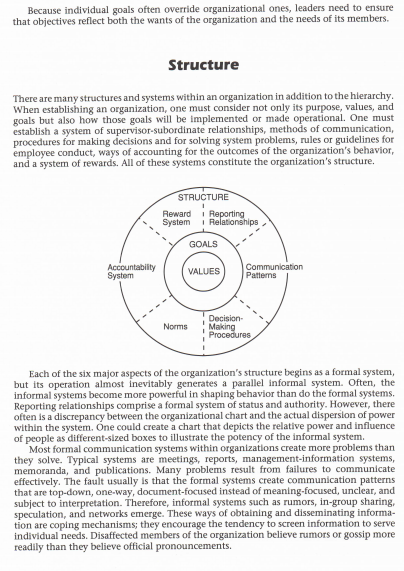

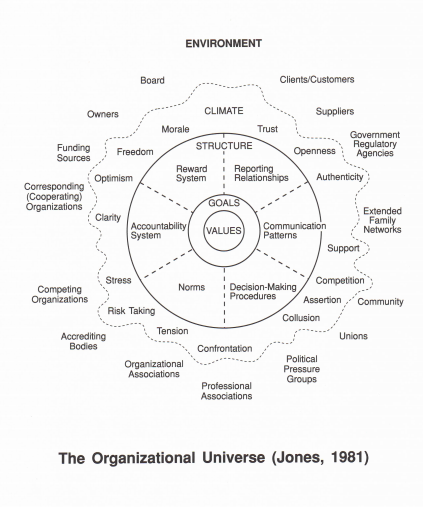

The Organizational Universe The organizational-universe model, developed by John E. Jones (1981), depicts organiza- tions as complex systems that consist of people, informal and/or formal groups, divisions, and so on. Organizations function within settings that often contain conflicting pressures. The organizational-universe model provides a basis for identifying the systems that consti- tute the organization before attempting to implement organizational change. Values At the core of any organization is a set of values-an underlying philosophy that defines the reasons for the organization's existence. As long as there is consensus on values among those who have power and influence within the organization, priorities generally are obvious and work is likely to be cooperative and coordinated. Commitment to a common set of values usually motivates people to work together in flexible ways. VALUES Reason for philosophy. purpose) Unfortunately, the values under which an organization operates frequently become lost in the shuffle of everyday work. For example, nonprofit organizations may find that obtaining funding has attained a higher priority than providing services. Organizational values affect the organization's purpose and management's philoso- phy. When these values are not held unanimously, the resulting tension can hinder organizational effectiveness. Managers may engage in "empire building" in order to further their careers at the expense of the entire system. Managers may need to consider specific organizational values in addition to the traditional ones of making a profit or of providing quality services. These internal organizational values include: Cooperation Functional impersonal conflict Strategic openness Acceptance of interdependence Achievement of objectives Respect and dignity In the Clarity treatment of people Acceptance of responsibility Commitment to studying the Thoroughness functioning of human systems 129Systematic problem solving Expressions of feelings as well Confrontation as points of view Providing and soliciting feedback Autonomy for individuals and groups Concreteness Proaction, rather than reaction Authenticity Experimentation Factors that affect organizational values often are covert and difficult to manage. Influential insiders and the prevailing reward system can shape the organization's value system. The stability of the work force and the focus of recruitment also can influence values. Crises, successes, and failures can lead to value shifts, as can the hierarchy, routine, and standardization. The permeability of the organization-its susceptibility to outside intrusion-can be a determinant of the stability of its core values. The resulting value changes generally lead to institutionalization, rigidity, looseness, pluralism, or chaos. Managers need to be aware of the value system underlying the operation of the organiza- tion to ensure that at least a moderate amount of consensus exists regarding the basic mission of the organization. To maintain organizational values, a manager must monitor the extent to which people have common assumptions, philosophies, and purposes; more importantly, the manager must exhibit value-oriented behavior. The following are steps that managers can take to focus employees' attention on values. 1. Keep organizational values explicit whenever possible. 2. Share one's values with one's subordinates. 3. Support and model commitment to organizational values. 4. Assess the fit between organizational values and subordinates' values. 5. Put value considerations on the agenda for meetings. 6. Question values as well as facts and procedures when problem solving. 7. Look for value differences ("shoulds" and "oughts") In conflict situations. 8. Avold win-lose arguments about values. 9. Update the organization's mission statement. 10. Set goals that are consistent with organizational values. Goals Organizational goals often are articulated values. For example, the goal statement "to increase our market share by 6 percent in the next twelve months" implies that the organization values growth. The goal "to develop and publicize a family-counseling service by October 1" may imply a value in expansion. GOALS VALUES ArticulatedThe most common organizational failings may be in the areas of goals, roles, and communication. The last two are affected adversely by lack of commitment to common goals. Lack of clarity with regard to goals can lead to disorganization, inefficiency, and Ineffectiveness. The goal-setting process needs to be made explicit whenever possible, and managers need to encourage employees to participate in goal setting. Meaningful participation leads to a sense of involvement and influence that generates psychological ownership, which in turn leads to commitment. There is no shortcut to commitment; it evolves within people when they perceive themselves as influential. Objectives are goals that have been made more specific, For example, a goal of improving the order-processing system may generate several objectives such as, "In the next quarter, reduce the data-processing time on an average order by thirty seconds." When objectives are highly specific, they can be monitored more easily, but the people who implement them may lose sight of the overall goal and values beneath it. Management by objectives (MBO) programs fall more often than they succeed, usually for a combination of reasons: (a) they are imposed; (b) they inadvertently encourage individual objectives at the expense of group and system aims; (c) the initial enthusiasm for the program is not maintained; (d) the goal-setting process does not extend to lower-level employees; (e) people work on the more visible objectives; and (f) the programs are poorly implemented. As McConkie (1979) concludes from an extensive review of MBO, "It is the practice, not the theory, of MBO that is frequently faulty.. The most serious faults in MBO applications center around inadequate training for those implementing MBO and the lack of follow-up" (p. 472). When managing change, it is important to relate desired outcomes both to organiza- tional values and to the means available for attaining objectives. It may be useful to think about organizational change as having implications that range along a continuum from general to specific: General Value Goal Objective Strategy Tactic Specific Technique Managers must foster consciousness of the interrelationships between these aspects of change if those who implement changes are to have a proper perspective. The major managerial responsibilities of this approach are as follows; 1. Provide training in goal and objective setting for all personnel. 2. Model the process. (One school superintendent Initiated an MBO process for school principals by making a large poster of her objectives and displaying it in her reception area. People began to see its value and asked for assistance in setting objectives for themselves.) 3. Create mechanisms by which all employees participate in goal setting. 4. Advocate organizational values during goal setting. 5. Assess the clarity of goals in all work-oriented encounters. 6. Test commitment to organizational goals.Because individual goals often override organizational ones, leaders need to ensure that objectives reflect both the wants of the organization and the needs of its members. Structure There are many structures and systems within an organization in addition to the hierarchy. When establishing an organization, one must consider not only its purpose, values, and goals but also how those goals will be implemented or made operational. One must establish a system of supervisor-subordinate relationships, methods of communication, procedures for making decisions and for solving system problems, rules or guidelines for employee conduct, ways of accounting for the outcomes of the organization's behavior, and a system of rewards. All of these systems constitute the organization's structure. STRUCTURE Reward System 1 Reporting 1 Relationships GOALS Accountability System VALUES Communication Pallems Norms Decision- Making Procedures Each of the six major aspects of the organization's structure begins as a formal system, but its operation almost inevitably generates a parallel informal system. Often, the informal systems become more powerful in shaping behavior than do the formal systems. Reporting relationships comprise a formal system of status and authority. However, there often is a discrepancy between the organizational chart and the actual dispersion of power within the system, One could create a chart that depicts the relative power and influence of people as different-sized boxes to illustrate the potency of the informal system. Most formal communication systems within organizations create more problems than they solve. Typical systems are meetings, reports, management-information systems, memoranda, and publications. Many problems result from failures to communicate effectively. The fault usually is that the formal systems create communication patterns that are top-down, one-way, document-focused instead of meaning-focused, unclear, and subject to interpretation. Therefore, informal systems such as rumors, in-group sharing, speculation, and networks emerge. These ways of obtaining and disseminating informa- tion are coping mechanisms; they encourage the tendency to screen information to serve individual needs. Disaffected members of the organization believe rumors or gossip more readily than they believe official pronouncements.The decision-making procedures within the organizational structure are the formal and informal ways in which problems are solved. Regulations and precedents often govern the ways in which choices are made. The formal decision-making policy dictates how people should initiate reconsideration of a policy and how their requests should be handled. Because these formal procedures often are frustrating, informal ways of influencing decisions are developed. People resort to political behavior in order to obtain decisions that are satisfactory to them, and tension develops between the formal and informal systems. For example, the existence of an "old-boy network" that systematically excludes some classes of people (notably women and minorities) from participation in decision making invites the development of a competing formal system. This often results in a lose-lose situation, and organizational problem solving suffers as a result. Both formal and informal norms govern behavior, and often the informal ones are more powerful. Formal norms are explicit rules of conduct that govern such things as eating or smoking in offices, punctuality in reporting for work, safety, and dress codes. Informal norms (such as politeness, collusion not to confront, deference to authority, working for no pay on Saturdays) are developed within a peer-influence system. By consciously creating formal norms, managers can expect that more potent, informal expectations also will arise. The formal accountability system usually consists of the annual performance review, methods for measuring results of the behavior of individuals and groups, and a financial- accounting model. Unfortunately, informal accountability systems also appear. Managers may hold subordinates personally accountable for certain outcomes or may "get on the case" of a particular department, Formal methods of accountability usually suffer from problems of measurement (as in education) and from inadequate confrontation. Conse- quently, in some organizations there are many places to hide, and people collude not to confront incompetence. Instead of demoting or firing a loyal employee who has been overpromoted, an organization may create a new position: "vice president for rare events." An organization cannot withhold evaluation feedback, positive or negative, and expect individual and group effectiveness. The reward system is probably the most powerful determinant of individual and group behavior. Formal rewards usually include compensation, benefits (perks), and recognition programs such as "employee of the month." Informal rewards often prove to be the more motivating factors, however. Rewards such as a private office, more salaried lines on one's budget, and "strokes" during an important meeting are very influential in shaping individual and group behavior. The pay system may have less sallency for some individuals than opportunities for promotion, for recognition, or for additional responsibilities. Expectancy theory (Nadler & Lawler, 1980) states that people will behave in ways that they expect will produce valued outcomes. The organizational structure consists of interdependent systems, each of which has both formal and informal components. This is the operating core of the organizational universe and is the proper focus of organizational change. Problems that arise in the organization can be traced to deficiencies in these six systems. Vertical Intergroup problems (such as top versus middle management) often stem from difficulties in reporting relationships and in communication patterns. Horizontal intergroup conflict (such as manufacturing versus warehousing) can arise when there are ineffective accountability and reward systems. When decision-making procedures and norms are detrimental to specific classes of people, diagonal intergroup relations (such as black/white, male/female) became strained. Managers not only must monitor the effectiveness of all aspects of the structure but also must assess their joint effects. Some guidelines to this approach are: 1. Study the distribution of power within the organization.2. Institute process critiques in all meetings. (How are we doing in this meeting?) 3. Set up feedback loops so that information flows up the organization as well as down. 4. Establish procedures for correcting the negative effects of rumors. (For example, in a crisis, create a rumor-control center to provide accurate information.) 5. Experiment with consultative and consensus methods of decision making. 6. Conduct an assessment and diagnosis of organizational norms. 7. Provide training for managers in conducting performance reviews. 8. Confront inadequate performance in a problem solving way. 9. Develop employee participation in evaluating the pay-and-benefits system. 10. Look for Informal ways to reward people. 11. Schedule team-building sessions for groups that are in conflict with each other before staging an intergroup confrontation. Managing the structure of the organization requires continual assessment of the organization, both because it is the essential core of the system and because so many of its aspects are covert. Climate The climate of the organization is the psychological atmosphere. It is both a result of and a determinant of the behavior of people and groups. Gibb (1978) emphasizes that assessment of the organization's trust level is a starting point in the management of change. It is important for managers to recognize that the organizational climate and the attitudes of others cannot be controlled or changed directly. Attitudes can be thought of as rationalizations for behavior, if one changes the behavior, the attitudes eventually will catch up. Problems in the organizational climate are likely to have roots in the structure. To improve the climate, one must change the ways in which work is done, For example, talking about trust does not generate trust and may produce the opposite. The primary action steps indicated by this approach are: 1. Monitor attitudes and morale as well as organizational functioning. 2. Focus on problem identification and problem solving in: . Reporting relationships (role expectations, reorganization); . Communication patterns, especially in meetings; try outlawing memos; Decision-making procedures (consult with subordinates more often; experiment with consensus seeking in meetings); Norms (rules, pressures for group conformity); Accountability system (put some punch into the performance review; establish criteria for success); Reward system (initiate a multilevel review of salary administration; publish criteria for promotions and transfers).3. Include the disaffected as well as those who are satisfied when diagnosing causes of climate problems. 4. Push for visible results. An unhealthy organizational climate can hinder productivity and achievement. Man- agers must be sensitive to the effects of their behavior on the climate and they should examine the structure to find ways to improve conditions. Environment The organization exists in an environment with which it must interact. Although the environment differs for each organization, some considerations-such as the availability of energy-are almost universal. Organizations are not closed systems; they are open- their boundaries are permeable. In the organizational-universe model (see page 137), this permeability is depicted by an uneven line surrounding the climate dimension. The organization's internal structure must be flexible enough to cope with the unexpected. If the organization becomes excessively bureaucratic, its members become oriented to Internal rather than external realities. Consequently, they may lose their sensitivity to the environment, and the organization may become vulnerable. The reverse situation-in which forces in the environment are permitted to upset internal priorities- promotes disorganization. For example, a consulting firm may embrace the dictum, *The client is king." The problem is that any client could create havoc within the system at any time, and the resultant scramble could affect schedules, priorities, and other operations. Modern organizations are becoming increasingly permeable. The intrusions, in some cases, have affected their core values. Government regulations concerning safety and equal opportunity have struck at the heart of many organizations. A system created to manu- facture widgets does not necessarily function with similar effectiveness when it is asked to solve social problems. This requires the organization to shift its values, philosophy, and purpose. The organizational boundary often is ambiguous. Just as there are degrees of being "inside," there are degrees of being "outside" as well, because most people are members of more than one organization. Family and political ties can affect the organizational structure for better or for worse. In addition, a primary environment for one organization may be a secondary one for another. The macroeconomic environment is turbulent. Some ways in which managers can prepare to deal with environmental change are: 1. Monitor the organization's speed of response to changes in the environ- ment. 2. Assess the costs of the organization's current degree of permeability. 3. Establish clear policies regarding transactions with components of the environment. 4. Set goals; do not simply react to outside pressures.ENVIRONMENT Board Clients/Customers Owners CLIMATE Suppliers Morale Trust Government Funding STRUCTURE Regulatory Sources Freedom Openness Agencies Reward Reporting System Relationships Authenticity Corresponding Optimism (Cooperating) Organizations GOALS Clarity Extended Accountability VALUES Communication Family System Patterns Networks Support Stress Competing Norms 1 Decision-Making Competition Organizations I Procedures Assertion 1 " Community Risk Taking Collusion Accrediting Tension Unions Bodies Confrontation Organizational Political Associations Pressure Professional Groups Associations The Organizational Universe (Jones, 1981)