Question:

A Canadian packaging company wished to extend its activities in the area of convenience foods. It had pinpointed one particular area where it could supply pizza boxes to half a dozen chains of pizza restaurants which operated home delivery services. These chains relied on local suppliers for their pizza boxes and were unhappy with the products supplied, the irregular delivery and, above all, the cost.

Through intensive online research and consultation with the commercial section of the embassy of the People’s Republic of China, the Canadians had managed to find a packaging manufacturer near Shanghai that could provide pizza boxes at a very reasonable price in line with the specifications and quantities required – and deliver them within the deadlines set.

Negotiations by e-mail and phone had taken place and a deal seemed imminent. Before contracts could be signed, however, it was agreed that both the Chinese and Canadians should visit each other’s headquarters and meet face-to-face to establish complete confidence in their venture and to settle final details. The Chinese were to visit Canada and the Canadians were to fly to China two weeks later.

The Canadian company decided to pull out all the stops to give their visitors a reception they would never forget. They arranged an elaborate welcome ceremony in a five-star hotel, to be followed by an authentic Chinese dinner. Considerable attention was paid to all the details involved – some of the ingredients for the meal had even been specially imported for the occasion.

Eventually, the big day came and the Chinese guests were whisked by limousine to the hotel where they were greeted by the Canadian company’s president and management team. Despite the lavish words of praise from the Canadians in front of the hundred guests present, and the bonhomie everyone tried to engender, the Chinese remained reticent and very formal in their behaviour. During the meal the Chinese did not seem to appreciate the effort put into the food they were served. Moreover, they said very little and the attempts by the Canadians to keep the social conversation going eventually ended in silence on both sides. Despite being promised an exotic Chinese floor-show after the dinner, the delegation made their excuses (they were tired after their journey) and quietly retired to their rooms. The Canadians were surprised and disappointed. What had gone wrong?

Questions

1. Why were the Canadian hosts surprised by the behaviour of the Chinese? How do you think the Canadians expected the Chinese to behave?

2. Why do you think the Chinese behaved the way they did?

3. If you had to choose a word to describe Chinese culture, what would that word be?

4. Read the information on the fifth dimension one more time. Try to explain the Chinese author’s analysis by using the values described in Concept 2.1.

Transcribed Image Text:

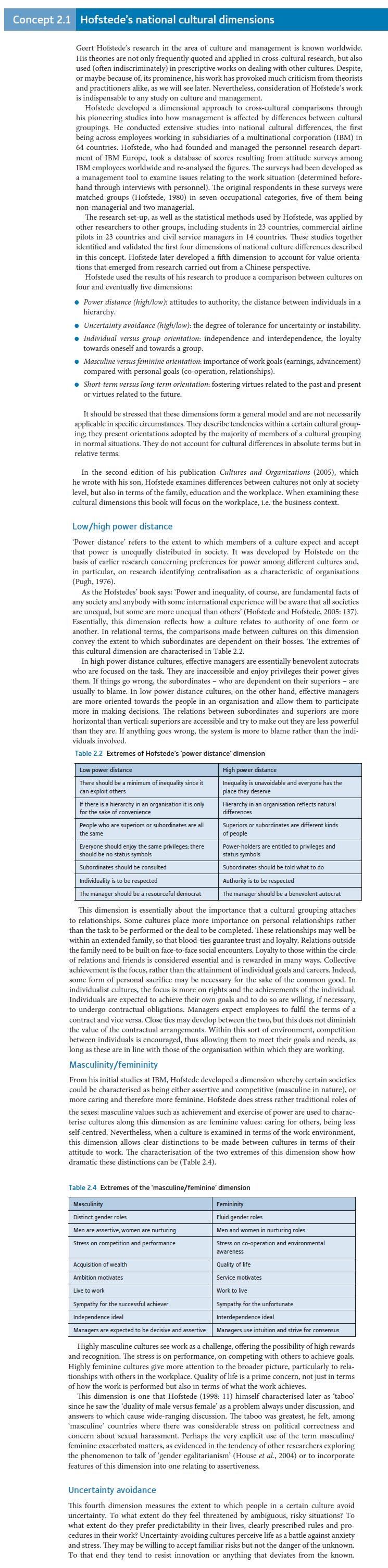

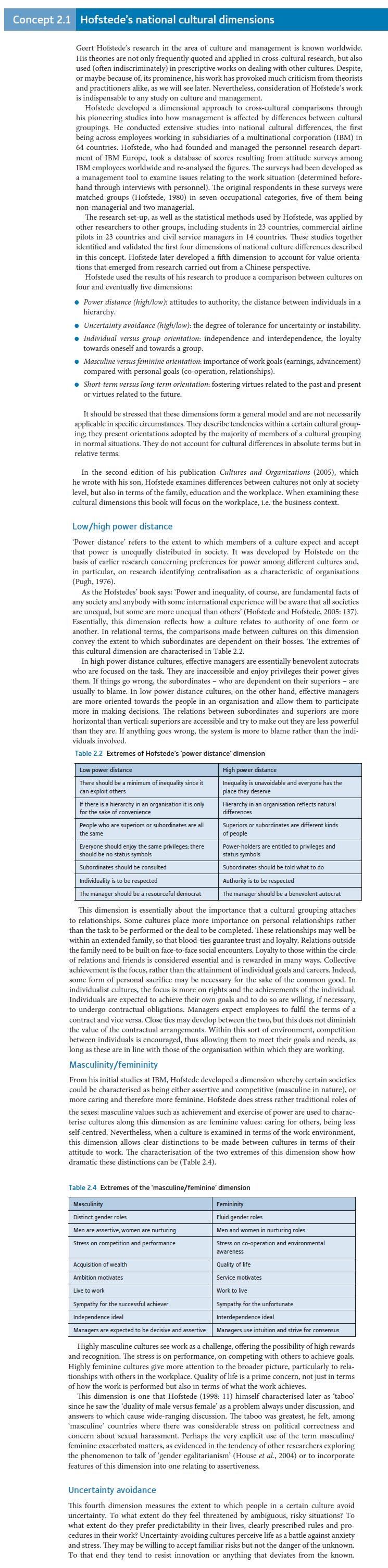

Concept 2.1 Hofstede's national cultural dimensions Geert Hofstede's research in the area of culture and management is known worldwide. His theories are not only frequently quoted and applied in cross-cultural research, but also used (often indiscriminately) in prescriptive works on dealing with other cultures. Despite, or maybe because of, its prominence, his work has provoked much criticism from theorists and practitioners alike, as we will see later. Nevertheless, consideration of Hofstede's work is indispensable to any study on culture and management. Hofstede developed a dimensional approach to cross-cultural comparisons through his pioneering studies into how management is affected by differences between cultural groupings. He conducted extensive studies into national cultural differences, the first being across employees working in subsidiaries of a multinational corporation (IBM) in 64 countries. Hofstede, who had founded and managed the personnel research depart- ment of IBM Europe, took a database of scores resulting from attitude surveys among IBM employees worldwide and re-analysed the figures. The surveys had been developed as a management tool to examine issues relating to the work situation (determined before- hand through interviews with personnel). The original respondents in these surveys were matched groups (Hofstede, 1980) in seven occupational categories, five of them being non-managerial and two managerial. The research set-up, as well as the statistical methods used by Hofstede, was applied by other researchers to other groups, including students in 23 countries, commercial airline pilots in 23 countries and civil service managers in 14 countries. These studies together identified and validated the first four dimensions of national culture differences described in this concept. Hofstede later developed a fifth dimension to account for value orienta- tions that emerged from research carried out from a Chinese perspective. Hofstede used the results of his research to produce a comparison between cultures on four and eventually five dimensions: Power distance (high/low): attitudes to authority, the distance between individuals in a hierarchy. Uncertainty avoidance (high/low): the degree of tolerance for uncertainty or instability. Individual versus group orientation: independence and interdependence, the loyalty towards oneself and towards a group. Masculine versus feminine orientation: importance of work goals (earnings, advancement) compared with personal goals (co-operation, relationships). Short-term versus long-term orientation: fostering virtues related to the past and present or virtues related to the future. It should be stressed that these dimensions form a general model and are not necessarily applicable in specific circumstances. They describe tendencies within a certain cultural group- ing; they present orientations adopted by the majority of members of a cultural grouping in normal situations. They do not account for cultural differences in absolute terms but in relative terms. In the second edition of his publication Cultures and Organizations (2005), which he wrote with his son, Hofstede examines differences between cultures not only at society level, but also in terms of the family, education and the workplace. When examining these cultural dimensions this book will focus on the workplace, i.e. the business context. Low/high power distance 'Power distance' refers to the extent to which members of a culture expect and accept that power is unequally distributed in society. It was developed by Hofstede on the basis of earlier research concerning preferences for power among different cultures and, in particular, on research identifying centralisation as a characteristic of organisations (Pugh, 1976). As the Hofstedes' book says: 'Power and inequality, of course, are fundamental facts of any society and anybody with some international experience will be aware that all societies. are unequal, but some are more unequal than others' (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005: 137). Essentially, this dimension reflects how a culture relates to authority of one form or another. In relational terms, the comparisons made between cultures on this dimension. convey the extent to which subordinates are dependent on their bosses. The extremes of this cultural dimension are characterised in Table 2.2. In high power distance cultures, effective managers are essentially benevolent autocrats who are focused on the task. They are inaccessible and enjoy privileges their power gives them. If things go wrong, the subordinates who are dependent on their superiors - are usually to blame. In low power distance cultures, on the other hand, effective managers are more oriented towards the people in an organisation and allow them to participate more in making decisions. The relations between subordinates and superiors are more horizontal than vertical: superiors are accessible and try to make out they are less powerful than they are. If anything goes wrong, the system is more to blame rather than the indi- viduals involved. Table 2.2 Extremes of Hofstede's 'power distance' dimension Low power distance There should be a minimum of inequality since it can exploit others If there is a hierarchy an organisation it is only for the sake of convenience People who are superiors or subordinates are all the same Everyone should enjoy the same privileges; there should be no status symbols Subordinates should be consulted Individuality is to be respected The manager should be a resourceful democrat High power distance Inequality is unavoidable and everyone has the place they deserve Hierarchy in an organisation reflects natural differences Superiors or subordinates are different kinds of people Power-holders are entitled to privileges and status symbols Subordinates should be told what to do Authority is to be respected The manager should be a benevolent autocrat This dimension is essentially about the importance that a cultural grouping attaches to relationships. Some cultures place more importance on personal relationships rather than the task to be performed or the deal to be completed. These relationships may well be within an extended family, so that blood-ties guarantee trust and loyalty. Relations outside the family need to be built on face-to-face social encounters. Loyalty to those within the circle of relations and friends is considered essential and is rewarded in many ways. Collective achievement is the focus, rather than the attainment of individual goals and careers. Indeed, some form of personal sacrifice may be necessary for the sake of the common good. In individualist cultures, the focus is more on rights and the achievements of the individual. Individuals are expected to achieve their own goals and to do so are willing, if necessary, to undergo contractual obligations. Managers expect employees to fulfil the terms of a contract and vice versa. Close ties may develop between the two, but this does not diminish the value of the contractual arrangements. Within this sort of environment, competition between individuals is encouraged, thus allowing them to meet their goals and needs, as long as these are in line with those of the organisation within which they are working. Masculinity/femininity From his initial studies at IBM, Hofstede developed a dimension whereby certain societies could be characterised as being either assertive and competitive (masculine in nature), or more caring and therefore more feminine. Hofstede does stress rather traditional roles of the sexes: masculine values such as achievement and exercise of power are used to charac- terise cultures along this dimension as are feminine values: caring for others, being less self-centred. Nevertheless, when a culture is examined in terms of the work environment, this dimension allows clear distinctions to be made between cultures in terms of their attitude to work. The characterisation of the two extremes of this dimension show how dramatic these distinctions can be (Table 2.4). Table 2.4 Extremes of the 'masculine/feminine' dimension Masculinity Femininity Distinct gender roles Fluid gender roles Men are assertive, women are nurturing Men and women in nurturing roles Stress on competition and performance Stress on co-operation and environmental awareness Acquisition of wealth Ambition motivates Live to work Sympathy for the successful achiever Independence ideal Managers are expected to be decisive and assertive Highly masculine cultures see work as a challenge, offering the possibility of high rewards and recognition. The stress is on performance, on competing with others to achieve goals. Highly feminine cultures give more attention to the broader picture, particularly to rela- tionships with others in the workplace. Quality of life is a prime concern, not just in terms of how the work is performed but also in terms of what the work achieves. This dimension is one that Hofstede (1998: 11) himself characterised later as 'taboo' since he saw the 'duality of male versus female' as a problem always under discussion, and answers to which cause wide-ranging discussion. The taboo was greatest, he felt, among 'masculine' countries where there was considerable stress on political correctness and concern about sexual harassment. Perhaps the very explicit use of the term masculine/ feminine exacerbated matters, as evidenced in the tendency of other researchers exploring the phenomenon to talk of 'gender egalitarianism' (House et al., 2004) or to incorporate features of this dimension into one relating to assertiveness. Quality of life Service motivates Work to live Sympathy for the unfortunate Interdependence ideal Managers use intuition and strive for consensus Uncertainty avoidance This fourth dimension measures the extent to which people in a certain culture avoid uncertainty. To what extent do they feel threatened by ambiguous, risky situations? To what extent do they prefer predictability in their lives, clearly prescribed rules and pro- cedures in their work? Uncertainty-avoiding cultures perceive life as a battle against anxiety and stress. They may be willing to accept familiar risks but not the danger of the unknown. To that end they tend to resist innovation or anything that deviates from the known.