As a member of the Child Poverty Action Group compose under the heading of Advice to Claimants

Question:

As a member of the Child Poverty Action Group compose under the heading of Advice to Claimants a list of 'do's and dont's' for people in situations similar to those of the Baths and Longs. Base your answer on the information contained in the following extracts from an article entitled The Clothes Line by David Bull and Christopher I veson.

Although the weekly supplementary benefit is expected to cover its normal replacement, clothing is by far the most common item for which the Supplementary Benefits Commission makes lump-sum, exceptional needs payments

(ENPS). Bedding, which is not provided for in the weekly payment, follows some way behind, in second place.

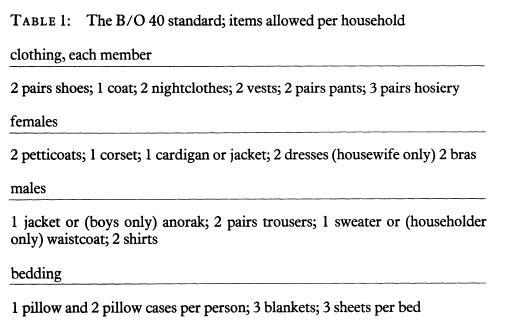

The average ENP is worth £8.20 and only two per cent exceed £20. Our sights were raised, however, when the Child Poverty Action Group acquired a copy of the SBC's internal document B/0 40 which officers use to determine a household's clothing and bedding requirements (see Table 1 ).

Bristol University social work and administration students, on fieldwork projects with the local CPAG branch, recently checked the needs, on the B/0 40 standard, of some 40 families. The outcome will be published later;

this article describes only the first two attempts. These left us asking why the two families received so much more than claimants we had helped before, and why, in spite of similar circumstances, they fared differently from each other.

Both families have four dependent children, are long-term claimants, and pay identical rents for houses on the same council estate. A casual visitor to the two homes would expect the 'Bath' family to need more than the 'Longs'.

Their home is ill-kept and sparsely furnished, and Mrs Bath is invariably badly dressed; while the Longs' home looks so warm and comfortable as to disguise, at first, the threadbare carpet and the family's worn furniture.

The Baths lacked, by the B/0 40 standard, 68 items of clothing and 33 of bedding; the Longs needed 57 and 21, respectively. These needs were spelled out in letters to the SBC, whose officers duly made a call. The Longs' visitor stayed half an hour, examined the bedding and asked to see all clothingeven tights! But the Baths' visitor examined neither clothing nor bedding.

The Longs received £44.90 and the Baths £50.15 (including £3.60 that the officer added, unsolicited, for lino in one room). The payments, however, were allocated for very different requirements. The Longs' award covered all of their bedding needs except for pillowcases; the parents received none of the garments they required; and the 20 items of clothing for the children were mostly inexpensive ones. The Baths, on the other hand, obtained only two sheets and no blankets, but nearly all the pillows and pillowcases that they requested and the clothing award, which was spread across the household, concentrated on the dearer items.

The discrepancy on bedding can be attributed to the different approaches of the visitors; but the clothing variations make nonsense of the commission's argument, at subsequent tribunal hearings, that the two families were expected to make 'normal replacement' of clothing.

We advised each family to appeal on two counts: the amounts awarded for some items; and the missing items. In his letter, Mr Long made clear his appeal on the first count, then added: 'Also, the grant did not cover all the items I required'. The tribunal chairman ruled that this was an aside and would only hear the first part of the appeal. The Longs were duly awarded £2.30 to make good the underpayment. The tribunal later agreed to hear the rest of the appeal; but meanwhile Mr Long had submitted a new, much reduced, claim. The chairman would not go through the outstanding items, one by one, and the tribunal arbitrarily awarded £ 16.20 for only eight of them.

The chairman at the Baths' hearing, on the other hand, methodically noted each outstanding requirement. He reprimanded the commission for failing to examine bedding and adjourned the hearing for a thorough revisit. Moreover the family had not received a properly completed form B/040A, telling them which items the grant covered and how much was allowed for each. It was therefore agreed that the revisit should take account of all the items that were needed now. We asked that it include also an examination of all floor coverings, as there were no grounds for singling out one room: all were as bad.

The officer who revisited agreed: he awarded £18.48 for four remaining rooms. Bedding to the value of £34.55 was awarded, leaving only two blankets and three sheets outstanding. Most of the £27.97 worth of clothes was underwear. Mr Bath's needs were mostly met, but his wife received nothing, possibly because she stormed out of the house when the officer, with all due thoroughness, asked 'whether I had any knickers'. When the hearing was reconvened, the tribunal decided that £ 131.15 was enough.

It certainly exceeded the Baths' wildest dreams - and ours. But why had the Longs received only half as much? It is, at best, difficult and, at worst, futile to attempt to monitor something so deliberately unscientific as the administration of discretion by the SBC and tribunals. Notwithstanding, we hope that our analysis of subsequent cases will offer a lesson or two. Indeed, a few tips for advocates emerge from the two initial cases.

New Society

Step by Step Answer:

Communication For Business And Secretarial Students

ISBN: 9780333261750

1st Edition

Authors: Lysbeth A Woolcott, Wendy R Unwin