Question: 1. How strong are the competitive forces confronting J. Crew in the market for specialty retail? Do a [Michael Porter] five-forces analysis to support your

1. How strong are the competitive forces confronting J. Crew in the market for specialty retail? Do a [Michael Porter] five-forces analysis to support your answer. (see chapter 3 in the textfor assistance] 2. What does your strategic group map of the specialty retail industry look like? Is J. Crew well positioned? Why or why not? [See example of strategic group map on page 69 and via google search; an explanation of the concepts is on pages 67 - 70. 3. What do you see as the key success factors in the market for speciality retailers? [see chapter 3 pages 72-73 for details on "key success factors"] 4. What does a SWOT analysis reveal about the overall attractiveness of J. Crew's situation? [see chapter 4 , page 93 in the text book for details on this concept] 5. What are the primary components of J. Crew's value chain? [see chapter 4, pages 95-99 in the text book] 6. What are the key elements of J. Crew's strategy? 7. Which one of the five generic competitive strategies discussed in chapter 5 most closely matches the competitive approach that J. Crew is employing. [See Table 5.1 on page 139 in the text book].

Chapter:3

In order to chart a company’s strategic course wisely, managers must first develop a deep understanding of the company’s present situation. Two facets of a company’s situation are especially pertinent: (1) its external environment—most notably, the competitive conditions of the industry in which the company operates; and (2) its internal environment—particularly the company’s resources and organizational capabilities.

Insightful diagnosis of a company’s external and internal environments is a prerequisite for managers to succeed in crafting a strategy that is an excellent fit with the company’s situation—the first test of a winning strategy. As depicted in Figure 3.1 , strategic thinking begins with an appraisal of the company’s external and internal environments (as a basis for deciding on a long-term direction and developing a strategic vision), moves toward an evaluation of the most promising alternative strategies and business models, and culminates in choosing a specific strategy.

This chapter presents the concepts and analytic tools for zeroing in on those aspects of a company’s external environment that should be considered in making strategic choices. Attention centers on the broad environmental context, the specific market arena in which a company operates, the drivers of change, the positions and likely actions of rival companies, and the factors that determine competitive success. In Chapter 4, we explore the methods of evaluating a company’s internal circumstances and competitive capabilities.

THE STRATEGICALLY RELEVANT FACTORS IN THE COMPANY’S MACRO-ENVIRONMENT

Every company operates in a broad “macro-environment” that comprises six principal components: political factors, economic conditions in the firm’s general environment (local, country, regional, worldwide), sociocultural forces, technological factors, environmental factors (concerning the natural environment), and legal/regulatory conditions.

Each of these components has the potential to affect the firm’s more immediate industry and competitive environment, although some are likely to have a more important effect than others (see Figure 3.2 ). An analysis of the impact of these factors is often referred to as PESTEL analysis, an acronym that serves as a reminder of the six components 46 PARTI Concepts and Techniques for Crafting and Executing Strategy FIGURE 3.1 rom Thinking Strategically about the Companys Situation to Choosing a Strategy Thinking strategically about a companys Select the external Form a Identify best environment strategic strategy promising vision of strategic where the options business Company for the model needs to Thinking for the Company head strategically Company about a companys nternal environment involved (political, economic, sociocultural, technological, environmental, legal/regulatory). Since macro-economic factors affect different industries in different ways and to different degrees, it is important for managers to determine which of these represent the most strategically relevant factors outside the firm’s industry boundaries. By strategically relevant, we mean important enough to have a bearing on the decisions the company ultimately makes about its long-term direction, objectives, strategy, and business model. The impact of the outer-ring factors depicted in Figure 3.2 on a company’s choice of strategy can range from big to small. But even if those factors change slowly or are likely to have a low impact on the company’s business situation, they still merit a watchful eye. For example, the strategic opportunities of cigarette producers to grow their businesses are greatly reduced by antismoking ordinances, the decisions of governments to impose higher cigarette taxes, and the growing cultural stigma attached to smoking. Motor vehicle companies must adapt their strategies to customer concerns about high gasoline prices and to environmental concerns about carbon emissions. Companies in the food processing, restaurant, sports, and fitness industries have to pay special attention to changes in lifestyles, eating habits, leisure-time preferences, and attitudes toward nutrition and fitness in fashioning their strategies. Table 3.1 provides a brief description of the components of the macro-environment and some examples of the industries or business situations that they might affect. As company managers scan the external environment, they must be alert for potentially important outer-ring developments, assess their impact and influence, and adapt the company’s direction and strategy as needed. However, the factors in a company’s environment having the biggest strategy-shaping impact typically pertain to the company’s immediate industry and competitive environment. Consequently, it is on a company’s industry and competitive environment that we concentrate the bulk of our attention in this chapter.

ASSESSING THE COMPANY’S INDUSTRY AND COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT

Thinking strategically about a company’s industry and competitive environment entails using some well-validated concepts and analytic tools. These include the five forces framework, the value net, driving forces, strategic groups, competitor analysis, and key success factors. Proper use of these analytic tools can provide managers with the understanding needed to craft a strategy that fits the company’s situation within their industry environment. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to describing how managers can use these tools to inform and improve their strategic choices.

THE FIVE FORCES FRAMEWORK

The character and strength of the competitive forces operating in an industry are never the same from one industry to another. The most powerful and widely used tool for diagnosing the principal competitive pressures in a market is the five forces frame-work.1 This framework, depicted in Figure 3.3 , holds that competitive pressures on companies within an industry come from five sources. These include (1) competition from rival sellers, (2) competition from potential new entrants to the industry, (3) competition from producers of substitute products, (4) supplier bargaining power, and (5) customer bargaining power. Using the five forces model to determine the nature and strength of competitive pressures in a given industry involves three steps: • Step 1: For each of the five forces, identify the different parties involved, along with the specific factors that bring about competitive pressures. • Step 2: Evaluate how strong the pressures stemming from each of the five forces are (strong, moderate, or weak). • Step 3: Determine whether the five forces, overall, are supportive of high industry profitability. Competitive Pressures Created by the Rivalry among Competing Sellers The strongest of the five competitive forces is often the rivalry for buyer patronage among competing sellers of a product or service. The intensity of rivalry among competing sellers within an industry depends on a number of identifiable factors. Figure 3.4 summarizes these factors, identifying those that intensify or weaken rivalry among direct competitors in an industry. A brief explanation of why these factors affect the degree of rivalry is in order:

• Rivalry increases when buyer demand is growing slowly or declining. Rapidly expanding buyer demand produces enough new business for all industry members to grow without having to draw customers away from rival enterprises. But in markets where buyer demand is slow-growing or shrinking, companies desperate to gain more business typically employ price discounts, sales promotions, and other tactics to increase their sales volumes at the expense of rivals, sometimes to the point of igniting a fierce battle for market share.

• Rivalry increases as it becomes less costly for buyers to switch brands. The less costly it is for buyers to switch their purchases from one seller to another, the easier it is for sellers to steal customers away from rivals. When the cost of switching brands is higher, buyers are less prone to brand switching and sellers have protection from rivalrous moves. Switching costs include not only monetary costs but also the time, inconvenience, and psychological costs involved in switching brands. For example, retailers may not switch to the brands of rival manufacturers because they are hesitant to sever long-standing supplier relationships or incur any technical support costs or retraining expenses in making the switchover

. • Rivalry increases as the products of rival sellers become less strongly differentiated. When rivals’ offerings are identical or weakly differentiated, buyers have less reason to be brand-loyal—a condition that makes it easier for rivals to convince buyers to switch to their offerings. Moreover, when the products of different sellers are virtually identical, shoppers will choose on the basis of price, which can result in fierce price competition among sellers. On the other hand, strongly differentiated product offerings among rivals breed high brand loyalty on the part of buyers who view the attributes of certain brands as more appealing or better suited to their needs. • Rivalry is more intense when there is excess supply or unused production capacity, especially if the industry’s product has high fixed costs or high storage costs. Whenever a market has excess supply (overproduction relative to demand), rivalry intensifies as sellers cut prices in a desperate effort to cope with the unsold inventory. A similar effect occurs when a product is perishable or seasonal, since firms often engage in aggressive price cutting to ensure that everything is sold. Like-wise, whenever fixed costs account for a large fraction of total cost so that unit costs are significantly lower at full capacity, firms come under significant pressure to cut prices whenever they are operating below full capacity. Unused capacity imposes a significant cost-increasing penalty because there are fewer units over which to spread fixed costs. The pressure of high fixed or high storage costs can push rival firms into price concessions, special discounts, rebates, and other volume-boosting competitive tactics.

• Rivalry intensifies as the number of competitors increases and they become more equal in size and capability. When there are many competitors in a market, companies eager to increase their meager market share often engage in price-cutting activities to drive sales, leading to intense rivalry. When there are only a few competitors, companies are more wary of how their rivals may react to their attempts to take market share away from them. Fear of retaliation and a descent into a damaging price war leads to restrained competitive moves. Moreover, when rivals are of comparable size and competitive strength, they can usually compete on a fairly equal footing—an evenly matched contest tends to be fiercer than a contest in which one or more industry members have commanding market shares and substantially greater resources than their much smaller rivals

. • Rivalry becomes more intense as the diversity of competitors increases in terms of long-term directions, objectives, strategies, and countries of origin. A diverse group of sellers often contains one or more mavericks willing to try novel or rule- breaking market approaches, thus generating a more volatile and less predictable competitive environment. Globally competitive markets are often more rivalrous, especially when aggressors have lower costs and are intent on gaining a strong foothold in new country markets.

• Rivalry is stronger when high exit barriers keep unprofitable firms from leaving the industry. In industries where the assets cannot easily be sold or transferred to other uses, where workers are entitled to job protection, or where owners are committed to remaining in business for personal reasons, failing firms tend to hold on longer than they might otherwise—even when they are bleeding red ink. Deep price discounting of this sort can destabilize an otherwise attractive industry. Evaluating the strength of rivalry in an industry is a matter of determining whether the factors stated here, taken as a whole, indicate that the rivalry is relatively strong, moderate, or weak. When rivalry is strong, the battle for market share is generally so vigorous that the profit margins of most industry members are squeezed to bare-bones levels. When rivalry is moderate, a more normal state, the maneuvering among industry members, while lively and healthy, still allows most industry members to earn acceptable profits. When rivalry is weak, most companies in the industry are relatively well satisfied with their sales growth and market shares and rarely undertake offensives to steal customers away from one another. Weak rivalry means that there is no downward pressure on industry profitability due to this particular competitive force. The Choice of Competitive Weapons Competitive battles among rival sellers can assume many forms that extend well beyond lively price competition. For example, competitors may resort to such marketing tactics as special sales promotions, heavy advertising, rebates, or low-interest-rate financing to drum up additional sales. Rivals may race one another to differentiate their products by offering better performance features or higher quality or improved customer service or a wider product selection. They may also compete through the rapid introduction of next-generation products, the frequent introduction of new or improved products, and efforts to build stronger dealer networks, establish positions in foreign markets, or otherwise expand distribution capabilities and market presence. Table 3.2 provides a sampling of the types of competitive weapons available to rivals, along with their primary effects with respect to price ( P ), cost ( C ), and value ( V )—the elements of an effective business model and the value-price-cost framework, as discussed in Chapter 1. Competitive Pressures Associated with the Threat of New Entrants New entrants into an industry threaten the position of rival firms since they usually compete fiercely for market share and add to the production capacity and number of rivals in the process. But even the threat of new entry increases the competitive pressures in an industry. This is because incumbent firms typically lower prices and increase defensive actions in an attempt to deter new entry when the threat of entry is high. Just how serious the threat of entry is in a particular market depends on two classes of factors: the expected reaction of incumbent firms to new entry and what are known as barriers to entry. The threat of entry is low when incumbent firms are likely to retaliate against new entrants with sharp price discounting and other moves designed to make entry unprofitable and when entry barriers are high.

Entry barriers are high under the following conditions: 2 • Industry incumbents enjoy large cost advantages over potential entrants. Existing industry members frequently have costs that are hard for a newcomer to replicate. The cost advantages of industry incumbents can stem from (1) scale economies in production, distribution, advertising, or other activities, (2) the learning-based cost savings that accrue from experience in performing certain activities such as manufacturing or new product development or inventory management, (3) cost-savings accruing from patents or proprietary technology, (4) exclusive partnerships with the best and cheapest suppliers of raw materials and components, (5) favorable locations, and (6) low fixed costs (because incumbents have older facilities that have been mostly depreciated). The bigger the cost advantages of industry incumbents, the riskier it becomes for outsiders to attempt entry (since they will have to accept thinner profit margins or even losses until the cost disadvantages can be overcome). • Customers have s trong brand preferences and high degrees of loyalty to seller. The stronger buyers’ attachment to established brands, the harder it is for a newcomer Types of Competitive Weapons Primary Effects Discounting prices, holding clearance sales Lowers price ( P ), increases total sales volume and market share, lowers profi ts if price cuts are not offset by large increases in sales volume Offering coupons, advertising items on sale Increases sales volume and total revenues, lowers price ( P ), increases unit costs ( C ), may lower profi t margins per unit sold ( P – C ) Advertising product or service characteristics, using ads to enhance a company’s image Boosts buyer demand, increases product differentiation and perceived value ( V ), increases total sales volume and market share, but may increase unit costs ( C ) and lower profi t margins per unit sold Innovating to improve product performance and quality Increases product differentiation and value ( V ), boosts buyer demand, boosts total sales volume, likely to increase unit costs ( C ) Introducing new or improved features, increasing the number of styles to provide greater product selection Increases product differentiation and value ( V ), strengthens buyer demand, boosts total sales volume and market share, likely to increase unit costs ( C ) Increasing customization of product or service Increases product differentiation and value ( V ), increases buyer switching costs, boosts total sales volume, often increases unit costs ( C ) Building a bigger, better dealer network Broadens access to buyers, boosts total sales volume and market share, may increase unit costs ( C ) Improving warranties, offering low- interest fi nancing Increases product differentiation and value ( V ), increases unit costs ( C ),increases buyer switching costs, boosts total sales volume and market share TABLE 3.2 Common “Weapons” for Competing with Rivals to break into the marketplace. In such cases, a new entrant must have the financial resources to spend enough on advertising and sales promotion to overcome customer loyalties and build its own clientele. Establishing brand recognition andbuilding customer loyalty can be a slow and costly process. In addition, if it is difficult or costly for a customer to switch to a new brand, a new entrant may have to offer a discounted price or otherwise persuade buyers that its brand is worth the switching costs. Such barriers discourage new entry because they act to boost financial requirements and lower expected profit margins for new entrants. • Patents and other forms of intellectual property protection are in place. In a number of industries, entry is prevented due to the existence of intellectual property protection laws that remain in place for a given number of years. Often, companies have a “wall of patents” in place to prevent other companies from entering with a “me too” strategy that replicates a key piece of technology. • There are strong “network effects” in customer demand. In industries where buyers are more attracted to a product when there are many other users of the product, there are said to be “network effects,” since demand is higher the larger the network of users. Video game systems are an example, since users prefer to have the same systems as their friends so that they can play together on systems they all know and can share games. When incumbents have a large existing base of users, new entrants with otherwise comparable products face a serious disadvantage in attracting buyers. • Capital requirements are high. The larger the total dollar investment needed to enter the market successfully, the more limited the pool of potential entrants.The most obvious capital requirements for new entrants relate to manufacturing facilities and equipment, introductory advertising and sales promotion campaigns, working capital to finance inventories and customer credit, and sufficient cash to cover startup costs. • There are difficulties in building a network of distributors/dealers or in securing adequate space on retailers’ shelves. A potential entrant can face numerous distribution-channel challenges. Wholesale distributors may be reluctant to take on a product that lacks buyer recognition. Retailers must be recruited and convinced to give a new brand ample display space and an adequate trial period. When existing sellers have strong, well-functioning distributor–dealer networks, a newcomer has an uphill struggle in squeezing its way into existing distribution channels. Potential entrants sometimes have to “buy” their way into wholesale or retail channels by cutting their prices to provide dealers and distributors with higher markups and profit margins or by giving them big advertising and promotional allowances. As a consequence, a potential entrant’s own profits may be squeezed unless and until its product gains enough consumer acceptance that distributors and retailers are anxious to carry it. • There are restrictive regulatory policies. Regulated industries like cable TV, telecommunications, electric and gas utilities, radio and television broadcasting, liquor retailing, and railroads entail government-controlled entry. Government agencies can also limit or even bar entry by requiring licenses and permits, such as the medallion required to drive a taxicab in New York City. Government- mandated safety regulations and environmental pollution standards also create entry barriers because they raise entry costs. • There are restrictive trade policies. In international markets, host governments commonly limit foreign entry and must approve all foreign investment applications. National governments commonly use tariffs and trade restrictions (antidumping rules, local content requirements, quotas, etc.) to raise entry barriers for foreign firms and protect domestic producers from outside competition. Figure 3.5 summarizes the factors that cause the overall competitive pressure from potential entrants to be strong or weak. An analysis of these factors can help managers determine whether the threat of entry into their industry is high or low, in general. But certain kinds of companies—those with sizable financial resources, proven competitive capabilities, and a respected brand name—may be able to hurdle an industry’s entry barriers even when they are high. 3 For example, when Honda opted to enter the U.S. lawn-mower market in competition against Toro, Snapper, Craftsman,John Deere, and others, it was easily able to hurdle entry barriers that would have been formidable to other newcomers because it had long-standing expertise in gasoline engines and a reputation for quality and durability in automobiles that gave it instant credibility with homeowners. As a result, Honda had to spend relatively little on inducing dealers to handle the Honda lawn-mower line or attracting customers.

Case study

J Crew In early 2014, Mickey Drexler, CEO of J.Crew Group, Inc., had some important decisions to make. In 2012, after J.Crew customers complained that the company’s latest product offerings consisted of far too many funky patterns with a younger-looking style—as opposed to consisting of a wide and fashionable selection of preppy button downs and classic khakis— Drexler decided that J.Crew’s 2013 fall line should, once again, feature conservative, but fashionably appealing, button-down shirts, classic blouses, sweaters, skirts, and trousers. However, fall sales were lackluster, producing an alarming 42 percent drop in profits from the fourth quarter of 2012. Drexler was perplexed, feeling that he and the company’s designers had tried their best to listen to customers’ feedback and respond to their complaints and dislikes. As he prepared for a meeting with Jenna Lyons, creative director, he wanted to consider a range of economic, cultural, and financial factors in deciding on the company’s approach to its fall 2014 lineup of offerings. It was important for the company to arrive at the best strategy to rejuvenate sales and rekindle consumer interest in shopping at J.Crew. If it did not, J.Crew risked losing the sales boost that came from news reports that such high-profile personalities as First Lady Michelle Obama and Britain’s Prince William and Kate Middleton shopped at J.Crew. Most important, of course, was developing a strategy to reverse the company’s recent decline and achieve the following objectives: • Attract consumers to J.Crew’s stores in much greater numbers. • Boost the company’s revenue, profitability, and overall brand strength. • Position the company for profitable long-term growth.

COMPANY HISTORY AND BACKGROUND

J.Crew was founded in 1947 under the name Popular Sales Club. It was a startup company that specialized in door-to-door sales of women’s clothing. Over the years, the firm grew, and in the 1980s, its executives saw a new opportunity. Catalog sales for companies such as L.L.Bean and Lands’ End were booming, and the executives wanted their company to share in the boom. In 1983, Popular Sales Club mailed out its first 100-page catalog, filled with models wearing the latest fashions. As sales began to grow, the company changed its name to J.Crew in hopes of catching the preppy, affluent consumer’s attention. Over the following years, J.Crew developed a loyal following by having a distinct image that the younger generations found appealing. By 1992, J.Crew had reached $70 million in sales. In 1989, J.Crew opened its first retail store at South Street Seaport in Manhattan. However, during the early 90s annual sales from the catalog business started to stagnate, and J.Crew realized it was time to make a change in its strategy.

A new CEO was named in 2003, Mickey Drexler, and he was ready to watch J.Crew expand into the fashion-forward company he dreamed it could be. Drexler is better known as the man who grew The Gap from a $400 million company to a $14 billion competitor. After he became CEO of J.Crew, the company rolled out an expansion plan. The store opened entirely new lines, such as Crewcuts, for children, and Weddings, for the entire bridal party. Crewcuts had almost 100 shopping locations throughout the United States in 2014, while the Weddings line had nine retail stores. In 2008, Drexler hired Jenna Lyons to be the new creative director. Lyons, known for her fashion forward thinking, quickly decided that J.Crew needed to revamp its classic image. At the company website, instead of finding pages and pages of classic button downs and nautical sweaters, now the consumer found edgy vests, bold patterns, and even stiletto heels.

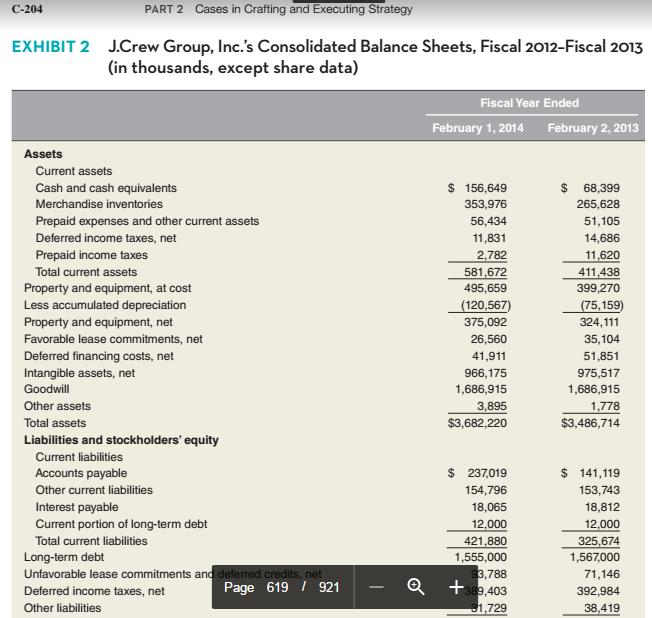

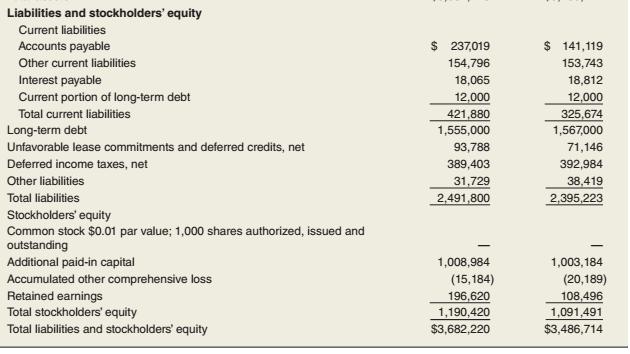

Not all of J.Crew’s loyal followers were impressed with the new change, with many disappointed that the company had abandoned its loyal customers who had been attracted to its traditional styles. Drexler responded by admitting that the styling might have gone too far and that changes should be made in the upcoming collection. The company’s strategic changes had produced hoped-for revenue gains, but its net income and liquidity had steadily declined since 2009. On March7, 2011, J.Crew Group, Inc., was acquired by TPG Capital, LP, and Leonard Green & Partners for approximately $3.1 billion, including the incurrence of $1.6 billion of debt. A summary of the company’s financial and operating performance for fiscal 2009 through fiscal 2013 is presented in Exhibit 1 . The company’s complete consolidated balance sheets for fiscal 2012 and fiscal 2013 are presented in Exhibit 2 .

OVERVIEW OF THE U.S. APPAREL INDUSTRY

The U.S. women’s apparel industry was a $42 billionindustry made up of over 29,000 different businesses, with a projected growth rate of 3.6 percentfrom 2013 to 2018. This would result in its becoming a $50 billion industry annually. Because of the recession, the industry took a large hit in 2008 and its profitability fell by 3.1 percent. The recession, coupled with the rising price of cotton, caused less demand for discretionary products, such as women’s clothing. However, it was expected that as the economy picked up, women would begin to purchase all the clothing they postponed purchasing during the recession.

The projected compound growth of cotton prices between 2009 and 2014 was 7.3 percent due to an increased demand for cotton. China had been slowly building a stockpile of cotton, and this was causing a global shortage of cotton, which in turn was causing a spike in the price. The global price of cotton drastically jumped from 62.75 cents per pound to 103.55 cents per pound in the year 2010.

The increase in the price of cotton caused the retailers’ overhead costs to increase as well. Because of the increased price of cotton, it became essential for the retailers to manage their purchases and overhead costs. The U.S. apparel industry was highly driven by imports. It was projected that by 2018, 78.6 percent of the products in the market would be imported from countries such as China and Vietnam. Despite the negative downturn, the industry continued to grow, and the number of stores was expected to continue to increase at a rate of 2.3 percent annually to roughly 61,200 by 2018. As consumer spending continued to increase, it would entice more companies to enter the industry. Although the industry was in the mature stage, the forecast growth potential and the increasing consumer attitude would keep the industry fully functional. Demand inside this industry was highly dependent on women aged 20 to 64 but, more specifically, on those aged 20 to 39 due to their larger amount of disposable income. The number of women in this age demographic was predicted to increase slowly through 2018. Almost one-third of the revenues inside the industry came from purchases of tops and blouses. Pants, denims, and shorts made up 24 percent of the total sales, followed closely by dresses and outerwear, with 18 and 17 percent, respectively. The remaining 9 percent was from sportswear and other garments, including custom-made items. Demand in the apparel industry was also driven by factors such as brand name, disposable income, and fashion trends. Companies had to be on the forefront of the new fashion trends and had to anticipate what consumers’ demands would be for the next fashion season.

J.Crew’s Strategy in 2014

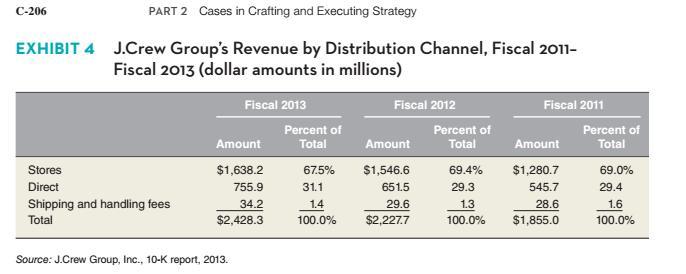

J.Crew delivered its products to customers through two main channels: retail stores and direct, which included websites and catalogs. J.Crew’s U.S. retail stores accounted for over 60 percent of the company’s overall revenue. The percentage of sales accounted for by women’s clothing had declined from 58 percent in 2011 to 55 percent in 2013. Accessories approximated 13 percent each year between 2011 and 2013. Children’s clothing accounted for 6 percent of sales for all three years. Sales of men’s clothing had increased from 23 percent of sales in 2011 to 25 percent in 2013. In 2013, the company sourced its merchandise from buying agents, as well as by purchasing directly from trading companies and manufacturers. The buying agents received commissions for placing orders with vendors, ensuring on-time deliveries, inspecting finished merchandise, and obtaining samples of the products during production. The top-10 vendors supplied 46 percent of J.Crew’s merchandise.

The company focused on projecting a consistent brand image by placing creative messages throughout its stores, websites, and catalogs that were designed to capture the attention of its shoppers. J.Crew perfected its consistency by keeping control over the pricing, production, and design of all its products.

Senior management was highly involved in all phases of production, from early design to the display of the final products throughout the stores. To promote its brand, J.Crew relied heavily on its catalog for advertising. In fiscal 2013, total catalog costs were around $45 million, while the company’s other advertising expenditures were about $39 million for the year. As of early 2014, J.Crew operated 265 J.Crew retail stores, 121 J.Crew Factory stores, and 65 Madewell stores, as well as its e-commerce websites.

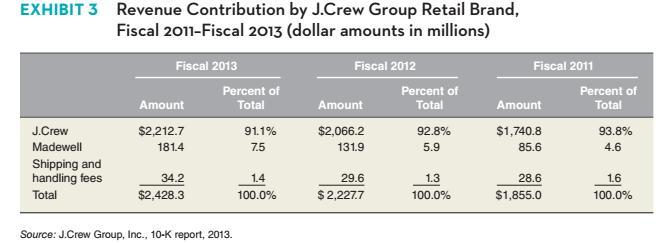

In 2014, J.Crew opened a third store in London and its first two stores in Hong Kong. Introduced in 2006, Madewell offered products exclusively for women, including perfect-fitting, heritage-inspired jeans, vintage-influenced tees, cardigans and blazers, boots, and jewelry and other accessories. Madewell products were sold through Madewell retail stores and the Madewell website. Exhibit 3 presents J.Crew Group’s revenues by retail brand for fiscal 2011 through fiscal 2013. The company’s revenue by distribution channel for 2011 through 2013 is presented in Exhibit 4 .

EXPANSION

J.Crew worked hard to stay at the forefront of fashion and deliver exactly what consumers desired. In 1989, J.Crew opened its first retail store in downtown Manhattan. It was there that J.Crew developed its classic style and gained a loyal following. The store focused on upper-middle-class customers and aimed to provide them with leisurewear at a price point between Ralph Lauren and The Limited.

Originally, the store offered products such as blouses, pants, and jackets. Over the years, J.Crew increased its product offerings exponentially, and the store offered products such as swimwear, lounge wear, sweaters, tees, suits, and accessories. A typical shirt cost between $65 and $350 and pants cost $75 to $750 depending on fabrics and collections. J.Crew extended not only its product depth but also its product breadth. The company engaged in major expansion and added lines for children, men, and even the wedding party.

In 1988, J.Crew Factory was launched. While many people assumed this store was a typical outlet store that just offered last season’s leftovers, it was actually a different line created with slightly different fabrics or designs that enabled a lower price point. All products were created on the basis of other popular designs. J.Crew Factory offered products such as tops, jackets, pants, swimwear, and dresses. A typical shirt cost between $25 and $100, depending on the fabric used. The Factory stores were often located in strip malls and focused on selling styles that had already been proved successful.

In 2006, Madewell, a subsidiary of J.Crew, was opened to exclusively target the younger female generation by offering more trendy clothing at a lower price point. Madewell offered products such as denims, dresses, shoes, and tops. The cost of shirts ranged from $25 to $150, while jeans cost, on average, $130 a pair. Crewcuts offered products for boys and girls between the ages of 2 and 12, thus serving parents who wanted to dress their kids in trendy clothes. Crewcuts featured products such as shirts, skirts, dresses, sweaters, pants, and swimwear. Shirt prices ranged from about $25 to $50, and pants cost around $50 to $80. J.Crew Wedding provided styles for the entire wedding party. The bride could pick out her dream gown while also selecting a new suit for her groom.

The store also offered over 50 different styles and colors for bridesmaid’s dresses. In the suiting department, groomsmen could choose from a wide selection of suits and tuxedos, as well as ties, shoes, and belts. The Weddings line also offered choices for ring bearers and flower girls.

In the early 2000s, J.Crew began to think about global expansion, and it opened its first store in Canada in 2011. In 2013, it was reported that London’s Regent Street would be J.Crew’s first European location and that locations would soon be announced for cities such as Tokyo and Hong Kong. The company was already shipping to over 100 countries world wide as a result of sales on its e-commerce website. As the company expanded, there were important factors to consider. Drexler had mentioned that with expansion comes unfamiliar territory. One major factor that had to be considered was sizing. J.Crew was known for its consistent sizing; however, in some areas of the world, people had smaller body frames than Americans. Also, less tangible factors needed to be considered, such as culture. Did all cultures dress as conservatively as the American loyal followers of J.Crew?

J.CREW’S RIVALS IN THE SPECIALTY RETAILING INDUSTRY

The women’s apparel industry was a competitive market with many factors that could determine success. Companies had to compete with other women’s clothing stores on factors such as marketing, product availability, designs, price, quality, service, shipping prices, and brand image. The retail industry also had to compete with one-stop shops such as Walmart and Costco. These stores often offered lower prices, and they were very successful during the recession. The continued growth of e-commerce companies was another factor that retail stores had to consider, because e-commerce competitors often offered lower prices, free shipping, and promotional offers.

The Mid-Atlantic region had the highest-level concentration of revenues, at 25 percent. The concentration was highly dependent on population as well as per capita income. The higher the income and the larger the population in an area, the more concentrated the retail stores were in that area. In a close second place was the Southeast region, which accounted for 23.2 percent of all revenues in the industry. While the national income level was $62,900, the average income in the Mid-Atlantic region was higher, at $72,800. The average income in the Southeast was considerably lower, at $55,000 annually. These statistics showed that the Southeast population had less disposable income to spend on women’s clothing.

Firms had to work hard to establish their brand name. While the barriers to entry in this market were low, there was a high level of competition among successful brands. Concentration inside the industry was low, and the top-four major players held about 20 percent of the revenues in 2013. The four largest players were Ascena Retail Group Inc., Ann Inc., Forever 21, and Hennes & Mauritz (H&M) AB. The major players had several retail stores scattered throughout the country, while the independent retailers had fewer stores, typically operated on a local scale. The apparel industry was highly fragmented, with no one chain holding above 8 percent total market share. This was because of the high number of independent retailers and the vast availability of clothing and accessories. Between 2008 and 2013, concentration increased, and it was predicted to continue increasing over the coming years.

Ascena Retail Group, Inc.

Ascena was one of the largest specialty retailers in the United States in the women’s apparel industry, with 7.1 percent of the total market share. Ascena operated approximately 3,900 stores throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada. Some of its more popular stores were Justice, Dress Barn, Lane Bryant, and Catherines. In 2012, Ascena purchased the Charming Shoppes, which helped diversify its portfolio. The company focused on offering women comfortable, trendy clothes at a moderate price. Its diversified portfolio allowed the company to target girls and women from age 7 to age 50 in both regular and plus-sized attire. Lane Bryant offered items such as casual clothing and lingerie in women’s sizes 12 to 32. The Justice line was focused on young girls aged 7 to 14 and offered trendy skirts and tops.

Ascena’s moderately priced clothing allowed the company to be very successful during the recession and enabled it to gain a loyal following. The appeal of Ascena’s brands, product lines, and pricing allowed the company’s annual revenues to increase from approximately $1.7 billion in 2009 to more than $3.3 billion in 2013—see Exhibit 5.

Ann Inc.

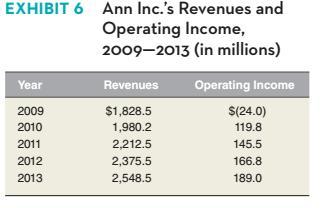

Ann Inc. had the second-largest market share inside the U.S. women’s apparel industry, with 5.6 percent of the market. In 2013, it operated approximately 1,000 stores in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada. Ann’s approach was to target women aged 25 to 55 who were willing to spend a little more income in order to wear more fashionable clothes. A financial summary for Ann Inc. for 2009 through 2013 is provided in Exhibit 6 . The company focused on offering a wide selection of merchandise, such as tops, dresses, loungewear, pants, suits, skirts, accessories, and shoes. Ann Inc. operated Ann Taylor, Ann Taylor Loft, and Ann Taylor Factory. In 2000, the company launched its website to compete on the e-commerce platform. Ann Inc. was projected to grow by 3 percent annually through

2014, making it a $2.5-billion-a-year company. The company claimed its success was based on its new product lines as well as its new locations, with over 60 additional stores opened recently. Because Ann Inc. competed at the “upper moderate” price point, sales numbers were affected due to the recession and profits dropped $371.1 million in 2009.

THE STATE OF THE TURNAROUND IN MID-2014

As the recession of the late 2000s hit, the industry experienced a decrease in demand for women’s apparel. Consequently, many retailers had to offer large discounts on clothing between 2008 and 2009. Because many consumers did not have large amounts of disposable income, a trend emerged: Rather than being concerned about the brand of their clothing as they had been in the past, consumers instead focused on the price and quality of merchandise. Some consumers changed their shopping preferences altogether and became more loyal to stores that offered trendy clothes at a lower price point. While J.Crew’s top management was at a crossroads of many different dilemmas, there was no clear path ahead. As the economy recovered, would consumers return to their previous habits of spending? Or would they be more conservative with their purchases in fear of another recession hitting? In addition, the increasing price sensitivity among consumers had put considerable pressure on J.Crew’s margins, and its recent acquisition by investment groups had added more than $1.5 billion in debt. As Mickey Drexler and the company’s chief managers prepared to meet to discuss the future of the company, they had many factors to consider. The most important questions were, What was the best strategy moving forward, and what changes would be necessary to provide attractive returns to the company’s shareholders?

PART 2 Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy EXHIBIT 2 J.Crew Group, Inc.'s Consolidated Balance Sheets, Fiscal 2012-Fiscal 2013 (in thousands, except share data) C-204 Assets Current assets Cash and cash equivalents Merchandise inventories Prepaid expenses and other current assets Deferred income taxes, net Prepaid income taxes Total current assets Property and equipment, at cost Less accumulated depreciation Property and equipment, net Favorable lease commitments, net Deferred financing costs, net Intangible assets, net Goodwill Other assets Total assets Liabilities and stockholders' equity Current liabilities Accounts payable Other current liabilities Interest payable Current portion of long-term debt Total current liabilities Long-term debt Unfavorable lease commitments and deferred credits, net Deferred income taxes, net Page 619 921 Other liabilities - Fiscal Year Ended February 1, 2014 $ 156,649 353,976 56,434 11,831 2,782 581,672 495,659 (120,567) 375,092 26,560 41,911 966,175 1,686,915 3,895 $3,682,220 $ 237,019 154,796 18,065 12,000 421,880 1,555,000 93,788 Q +389,403 31,729 February 2, 2013 $ 68,399 265,628 51,105 14,686 11,620 411,438 399,270 (75,159) 324,111 35,104 51,851 975,517 1,686,915 1,778 $3,486,714 $ 141,119 153,743 18,812 12,000 325,674 1,567,000 71,146 392,984 38,419

Step by Step Solution

3.52 Rating (166 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts