Please help me to resolve problem:

Case 7-6 Industrial Products Corporation In 1996 the Industrial Products Corporation (IPC) manufactured a variety of industrial products in more than a dozen divisions. Plants were located throughout the country, one or more to a division, and company headquarters was in a large Eastern city. Each division was run by a division manager and had its own balance sheet and income statement. The company made extensive use of long- and short-run planning programs, which included budgets for sales, costs, expenditures, and rate of return on investment. Monthly reports on operating results were sent in by each division and were reviewed by headquarters executives. For many years the principal performance measure for divisions had been their rate of return on investment. The Baker Division of IPC manufactured and assembled large industrial pumps, most of which sold for more than $5,000. A great variety of models were made to order from the standard parts which the division either bought or manufactured for stock. In addition, components were individually designed and fabricated when pumps were made for special applications. A variety of metalworking machines were used, some large and heavy, and a few designed especially for the division's kind of business. The division operated three plants, two of which were much smaller than the third and were located in distant parts of the country. Headquarters offices were located in the main plant where more than 1,000 people were employed. They performed design and manufacturing operations and the usual staff and clerical work. Marketing activities were carried out by sales engineers in the field, who worked closely with customers on design and installation. Reporting to Mr. Brandt, the division manager, were managers in charge of design, sales, manufacturing, purchasing, and budgets. The division's product line was broken down into five product groups so that the profitability of each could be studied separately. Evaluation was based on the margin above factory cost as a percentage of sales. No attempt was made to allocate investment to the product lines.The budget director said that not only would this be difficult in view of the common facilities, but that such a mathematical computation would not provide any new information since the products had approximately the same turnover of assets. Furthermore, he said, it was difficult enough to allocate common factory costs between products, and that even margin on sales was a disputable figure. "If we were larger," he said,"and had separate facilities for each product line, we might be able to do it. But it wouldn't mean much in this division right now." Only half a dozen people monitored the division's rate of return; other measures were used in the division's internal control system. The division manager watched volume and timeliness of shipments per week, several measures of quality, and certain cost areas such as overtime payments.

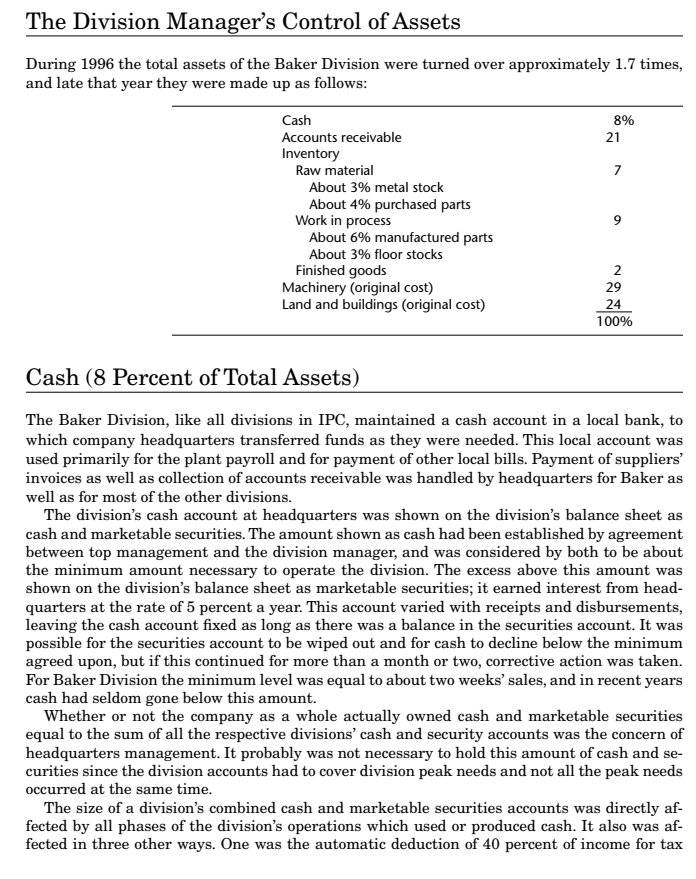

The Division Manager's Control of Assets During 1996 the total assets of the Baker Division were turned over approximately 1.? times, and late that year they were made up as follows: Cash 3% Accounts receivable 21 Inventory Raw material ? About 3% metal stock About 4% purchased part1 Work in process 9' About 6% manufactured parls About 3% oor stodcs Finished goods 2 Machinery {original cost} 29 Land and buildings (original cost} 24 1 00% Cash (8 Percent of Total Assets) The Baker Division, like all divisions in IP'C, maintained a cash account in a local bank, to which company hequarters transferred funds as they were needed. This local account was used primm'ily for the plant payroll and for payment of ether local bills. Payment ofsuppliers' invoices as well as collection of accounts receivable was handled by hequarters for Baker as well as for most of the other divisions. The division's cash account at headquarters was shown on the division's balance sheet as cash and marketable securities. The amount shown as cash had been established by agreement between top management and the division manager, and was considered by both to be about the minimum amount necessary to operate the division. The excess above this amount was shown on the division's balance sheet as marketable securities; it earned interest from head- quarters at the rate of 5 percent a year. This account varied with receipts and disbursements, leaving the cash account red as long as there was a balance in the securities account. It was possible for the securities account to be wiped out and for cash to decline below the minimum agreed upon1 but if this continued for more than a month or two, corrective action was taken. For Baker Division the minimum level was equal to about two weeks' sales, and in recent years cash had seldom gone below this amount. Whether or not the company as a whole actually owned cash and marketable securities equal to the sum of all the respective divisions' cash and security accounts was the concern of headquarters management. It probably was not necessary to hold this amount of cash and se- curities since the division accounts had to cover division peak needs and not all the peak needs occurred at the same time. The size of a division's combined cash and marketable securities accounts was directly af- fected by all phases ofthe division's operations which used or produced cash. It also was af- fected in three other ways. ne was the automatic deduction of 4!} percent of income for tar: purposesJLnother was the payment of \"dividends\" by the division to headquarters. All earnings that the division manager did not wish to keep for future use were transferred to the com- pany's cash account by payment of a dividend. Since a division was expected to retain a suf- cient balance to provide for capital expenditures, dividends were generally paid only by the protable divisions which were not expanding rapidly. The third action affecting the cash account occurred if cash declined below the minimum, or if extensive capital expenditures had been approved. A division might then \"borrow\" from headquarters, paying interest as if it were a separate company. At the end of 1996 the Baker Division had no loan and had been able to operate since about 1991) without borrowing from headquarters. Borrowing was not, in fact, currently being considered by the Baker Division. Except for its part in the establishment of a minimum cash level, top management was not involved in the determination of the division's investment in cash and marketable se- curities. Mr. Brandt could control the level of this investment by deciding how much was to be paid in dividends. Since only a 5 percent return was received on the marketable se- curities and since the division earned more than that on its total investment, it was to the division manager's advantage to pay out as much as possible in dividends. When asked how he determined the size of the dividends, Mr. Brandt said that he simply kept what he thought he would need to cover peak demands, capital expenditures, and contingencies. Improving the division's rate of return may have been part of the decision, but he did not mention it. Accounts Receivable (21 Percent of Total Assets) All accounts receivable for the Baker Division were collected at company headquarters. Arolmd the Eth of each month a report of balances was prepared and forwarded to the divi- $1011. Although in theory Ivlr. Brandt was allowed to set his own terms for divisional sales, in prac- tice it would have ben- diicult to change the company's usual terms. Since Baker Division sold to important customers of other divisions, any change from the net 31:! terms could disturb a large segment of the corporation's business. Furthermore, industry practice was well estab- lished, and the division would hardly try to change it. The possibility of cash sales in situations in which credit was poor was virtually nonexis- tent. Credit was investigated for all customers by the headquarters credit department and no sales were made without a prior credit check. For the Baker Division this policy presented no problem, for it sold primarily to well-established customers. In late 1996 accounts receivable made up 21 percent of total assets. The fact that this corre- sponded to 45 average days of sales and not to 3!} was the result of a higher than average level of shipments the month before, coupled with the normal delay caused by the billing and col- lection process. There was almost nothing Mr. Brandt could do directly to control the level of accounts re- euvable. This asset account varied with sales, lagged behind shipments by a little more than a month, and departed from this relationship only if customers happened to pay early or late. Inventory: Raw Material Metal Stock (About 3 Percent of Total Investment) In late 1996 inventory as a whole made up 18 percent of Baker Division's total assets. A sub- division of the various kinds of inventory showed that raw material accounted for '1' percent, work in process 9 percent, and nished goods and miscellaneous supplies 2 percent. Since the Baker Division produced to order, nished goods inventory was normally small, leaving raw material and work in process as the only signicant classes of inventory: The raw material inventory could be further subdivided to separate the raw material inven- tory from a variety of purchased parts. The raw material inventon was then composed primar- ily of metals and metal shapes, such as steel sheets or copper tubes. Most of the steel was bought accordingto a schedule arranged with the steel companies several months ahead of the delivery date. About a month before the steel company was to ship the order, Baker Division would send the rolling instructions by shapes and weights. If the weight on any particular shape was below a minimum set by the steel company; Baker Division would pay an extra charge for processing. Although this method of purchasing accounted for the bulk of steel purchases, smaller amounts were also bought as needed from warehouse stocks and specialty producers. Copper was bought by Madquarters and processed by the company's own mill. The divi- sions could buy the quantities they needed, but the price paid depended on corporate buying practices and processing costs. The price paid by Baker Division had generally been competi- tive with outside sources, though it often lagged behind the market both in increases and in reductions in price. The amounts of copper and steel bought were usually determined by the purchasing agent without recourse to any formal calculations of an economic ordering quantity. The reason for this was that since there was such a large number of uncertain factors that had continually to be estimated, a formal computation would not improve the process of determining how much to buy. Purchases depended on the amounts on hand, expected consumption, and current de- livery time and price expectations. li' delivery was fast, smaller amounts were usually bought. If a price increase was anticipated, somewhat larger orders often were placed at the current price. larger amounts of steel had been bought several years earlier, for example, just before expected labor action on the railroads threatened to disrupt deliveries. The level of investment in raw material varied with the rates of purchase and use. There was a fairly wide range within which Iillr. Brandt could control this class of asset, and there were no top management direives governing the size of his raw material inventory. Inventory: Purchased Parts and Manufactured Parts (About 10 Percent of Total Assets4 Percent in Raw Material, 6 Percent in Work in Process) The Baker Division purchased and manufactured parts for stock to be used later in the as- sembly of pumps. The method used to determine the purchase quantity was the same as that used to determine the length of production run on parts made for work-in-process stocks. Inventory: Floor Stocks (About 3 Percent of Total Investment) Floor stock inventory consisted of parts and components which were being worked on and as- sembled. Items became part of the floor stock inventory when they were requisitioned from the storage areas or when delivered directly to the production floor. Pumps were worked on individually so that lot size was not a factor to be considered. There was little Mr. Brandt could do to control the level of floor stock inventory except to see that there was not an excess of parts piled around the production area.Inventory: Finished Goods (2 Percent of Total Investment) As a rule, pumps were made to order and for immediate shipment. Finished goods inventory consisted of those few pumps on which shipment was delayed. IBontrol of this investment was a matter of keeping it low by shipping the pumps as fast as possible. Land, Buildings, and Machinery (53 Percent of Total Investment) Since the Baker Division's xed assets, stated at gross, comprised 53 percent of total assets at the end of 1996, the control of this particular group of assets was extremely ianortant. Changes in the level of these investments depended on retirements and additions, the latter being entirely covered by the capital budgeting program. Industrial Products Corporation's capital budgeting procedures were described in a plan- ning manual. The planning sequence was as follows: 1. Headquarters forecasts economic conditions. [March] 2. The divisions plan long-term objectives. [June] 3. Supporting programs are submitted. [September] These are plans for specic actions, such as sales plans, advertising programs, and cost reduction programs, and include the facilities program which is the capital expenditure request. The planning manual stated under the heading "General Approach in the Development of a Coordinated Supporting Program\" this advice: Formulation and evaluation of a Supporting Program for each product line can generally be im- proved if projects are classied by purpose. The key objective of all planning is Return-on-Assets, a inctionofldargin andTurnover. These ratios are in turn determined by the three factors in the business equationVolume, floats, and Assets. All projects therefore should be directed primarily at one ofthe following: i To increase volume; It To reduce costs and expenses; and i To minimise assets. 4. Annual objective submitted {November 11 by S an!) The annual objective states projected sales, costs, expenses, prots, cash expenditures, and receipts, and shows pro forma balance sheets and income statements. Mr. Brandt was nresponsible for the division's assets and for provision for the growth and expansion of the division.\" Growth referred to the internal renements of product design and production methods and to the cost reduction programs. Expansion involved a 5- to I'll- year program including about two years for construction. In the actual capital expenditure request there were four kinds of facilities proposals: 1. Cost reduction projects, which were self-liquidating investments. Reduction in labor costs was usually the largest source of the savings, which were stated in terms of the payback pe- riod and the rate of return. 2. Necessity projects. These included replacement of worn-out machinery, quality improve- ment and technical changes to meet competition, environmental compliance projects, and facilities for the safety and comfort of the workers. 3. Product redesign projects. 4. Expansion projects. Justification of the cost reduction proposals was based on a comparison of the estimated rate of return (estimated return before taxes divided by gross investment) with the 20 percent stan- dard as specified by headquarters. If the project was considered desirable, and yet showed a re- turn of less than 20 percent, it had to be justified on other grounds and was included in the ne- cessities category. Cost reduction proposals made up about 60 percent of the 1997 capital expenditure budget, and in earlier years these proposals had accounted for at least 50 percent. Very little of Baker Division's 1997 capital budget had been allocated specifically for product re- design and none for expansion, so that most of the remaining 40 percent was to be used for ne- cessity projects. Thus a little over half of Baker Division's capital expenditures were justified pri- marily on the estimated rate of return on the investment. The remainder, having advantages which could not be stated in terms of the rate of return, were justified on other grounds. Mr. Brandt was free to include what he wanted in his capital budgeting request, and for the three years that he had been division manager his requests had always been granted. How- ever, no large expansion projects had been included in the capital budget requests of the last three years. As in the 1997 budget, most of the capital expenditure had been for cost-reduction projects, and the remainder was for necessities. Annual additions had approximately equaled annual retirements. Since Mr. Brandt could authorize expenditures of up to $250,000 per project for purposes approved by the board, there was in fact some flexibility in his choice of projects after the bud- get had been approved by higher management. Not only could he schedule the order of ex- penditure, but under some circumstances he could substitute unforeseen projects of a similar nature. If top management approved $100,000 for miscellaneous cost reduction projects, Mr. Brandt could spend this on the projects he considered most important, whether or not they were specifically described in his original budget request. For the corporation as a whole, about one-quarter of the capital expenditure was for projects of under $250,000, which could be authorized for expenditure by the division managers. This proportion was considered by top management to be about right; if, however, it rose much above a quarter, the $250,000 dividing line would probably be lowered. Questions 1. To what extent did Mr. Brandt influence the level of investment in each asset category? 2. Comment on the general usefulness of return on investment as a measure of divisional per- formance. Could it be made a more effective device