Question: Please read chapter 8 and answer the questions and see the (guide to answer number 3) For each case study, you will view the material

Please read chapter 8 and answer the questions and see the (guide to answer number 3)

For each case study, you will view the material as the student's teacher, read the information provided and write a response that includes the following information:

1. Decide what assessment you would like to do to provide you with more information about the student,

2. Explain the concerns you have for each student regarding the areas that they are struggling with as readers and

3. Describe the instructional strategies you will use in your classroom with these students, try to share 2 - 3 instructional strategies, and tell why you chose those strategies and why you would do the assessments and instructional strategies?

(Guide)

\

\

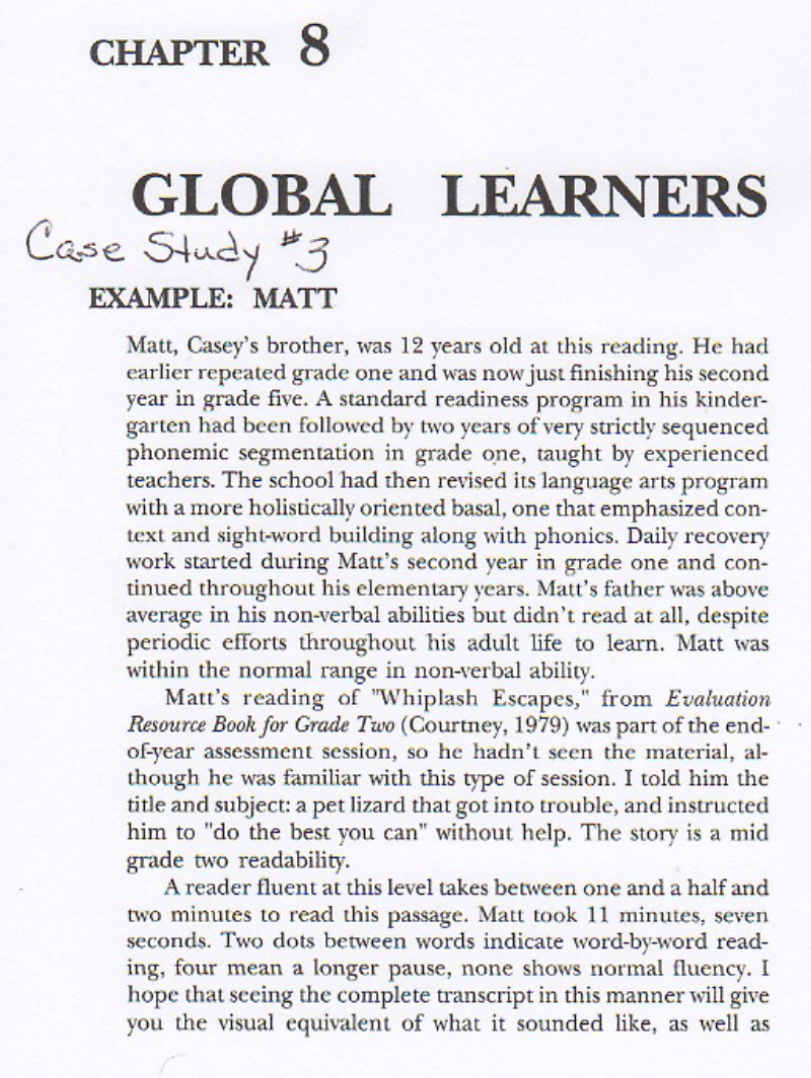

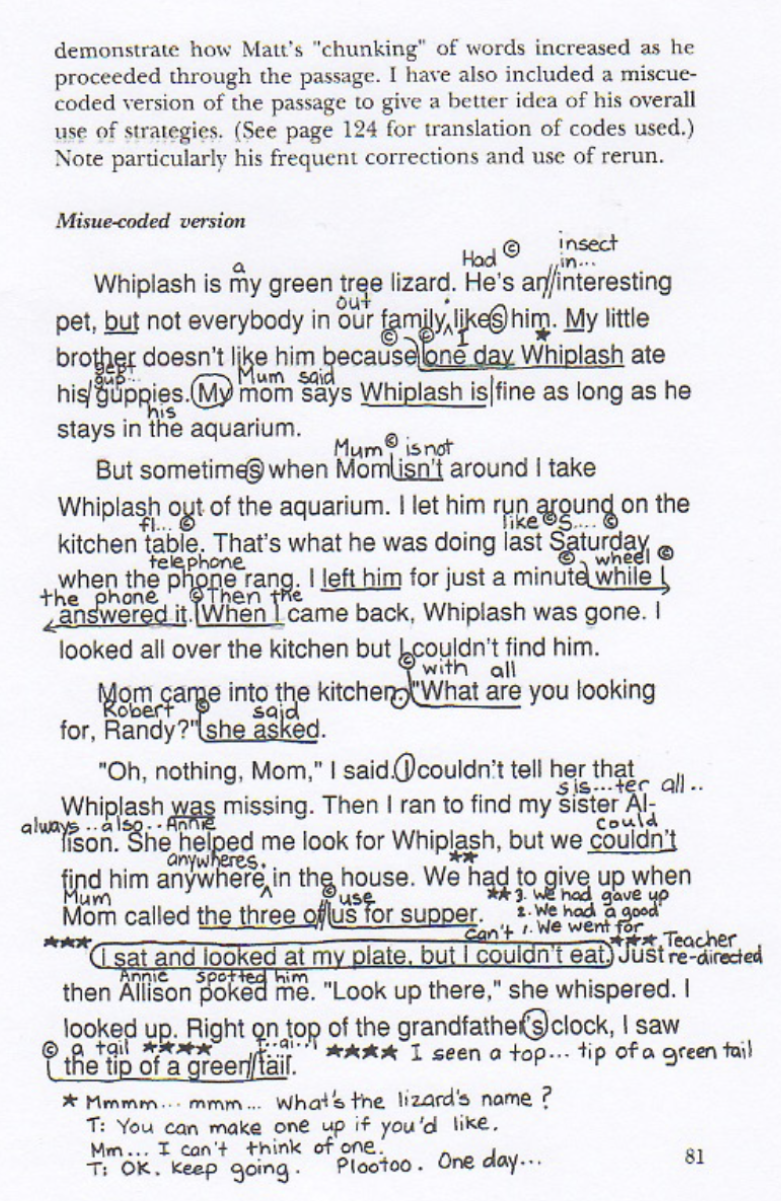

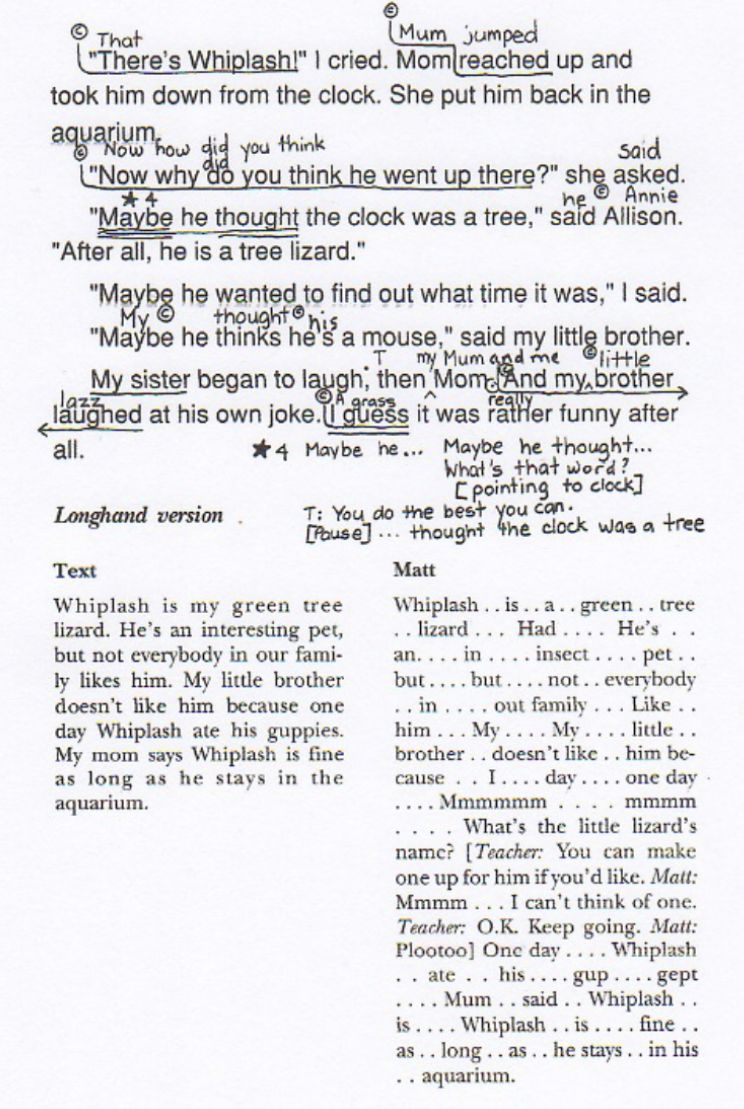

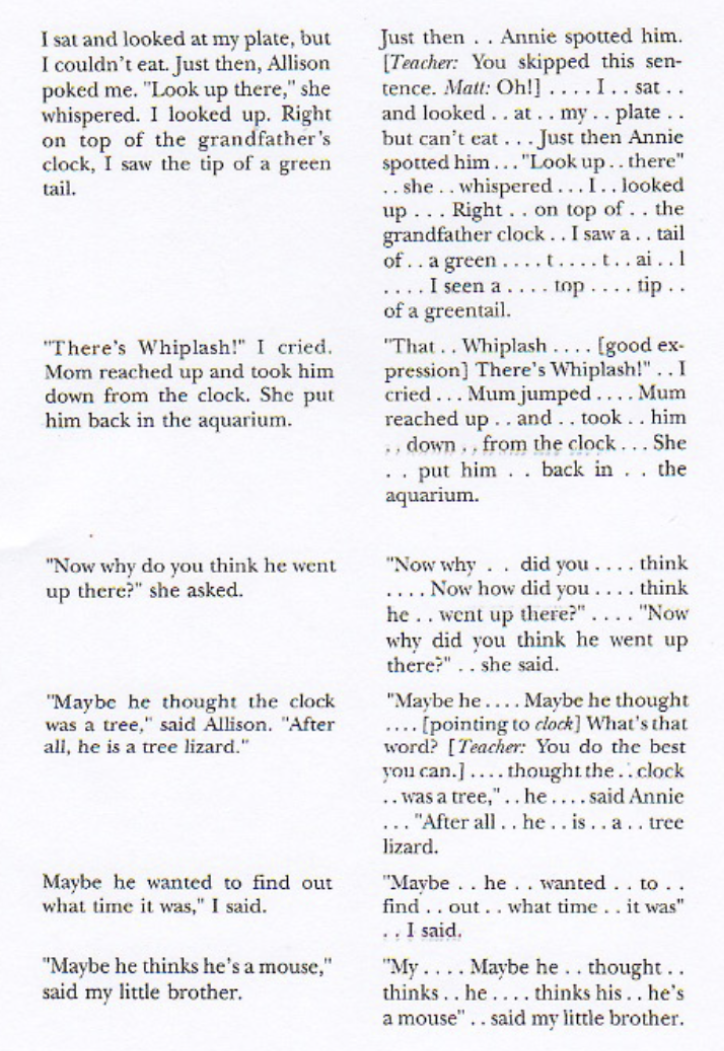

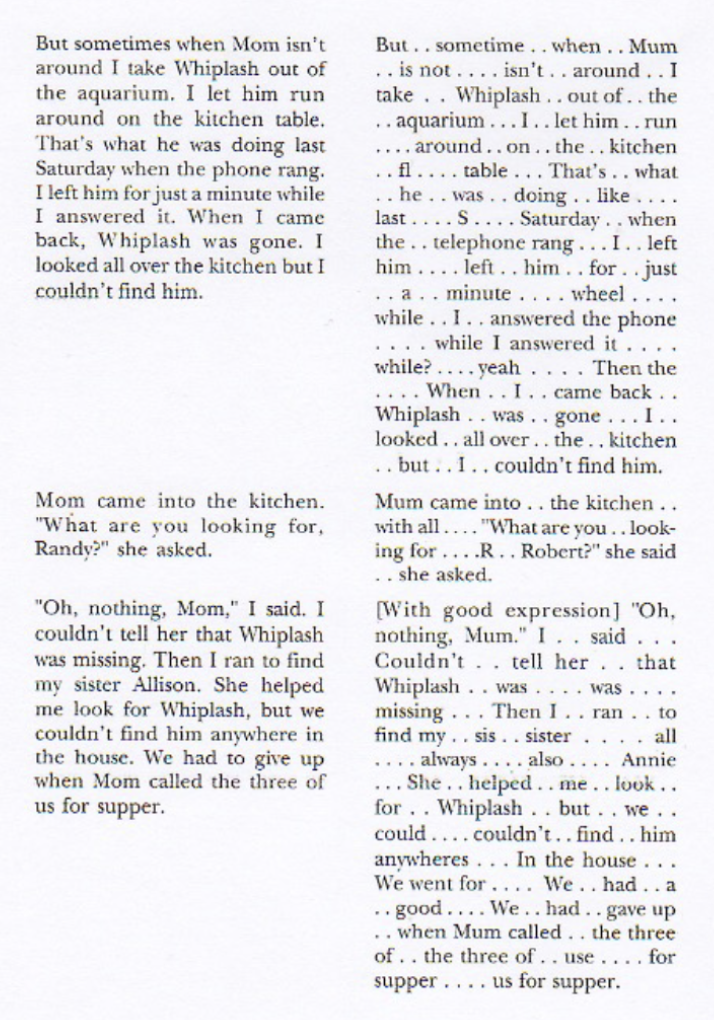

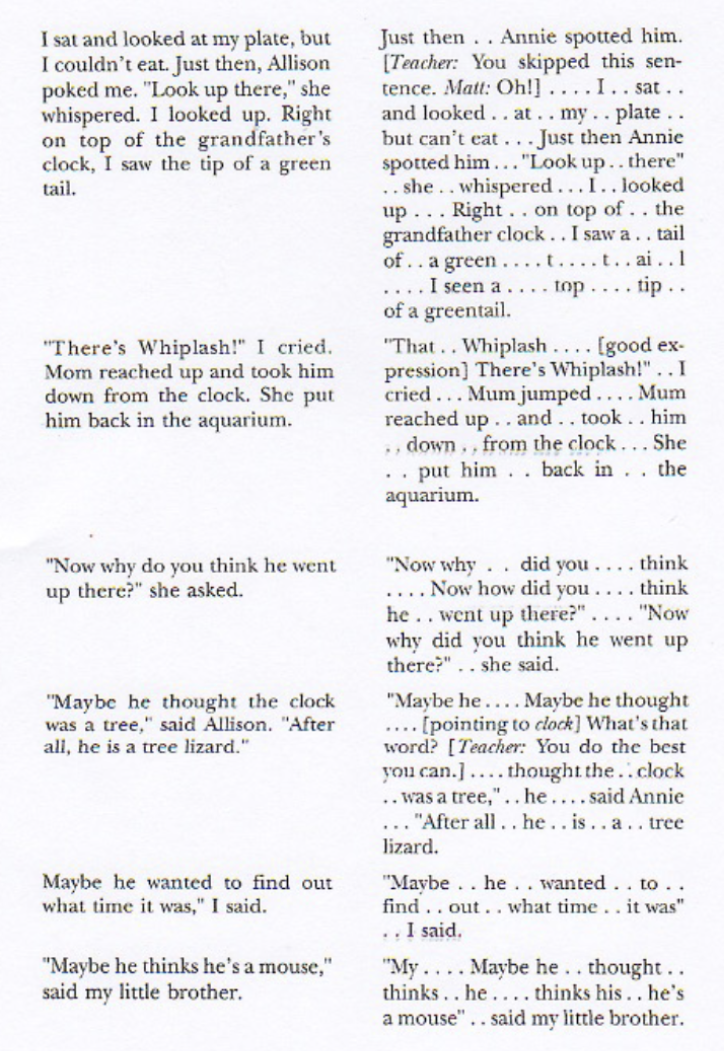

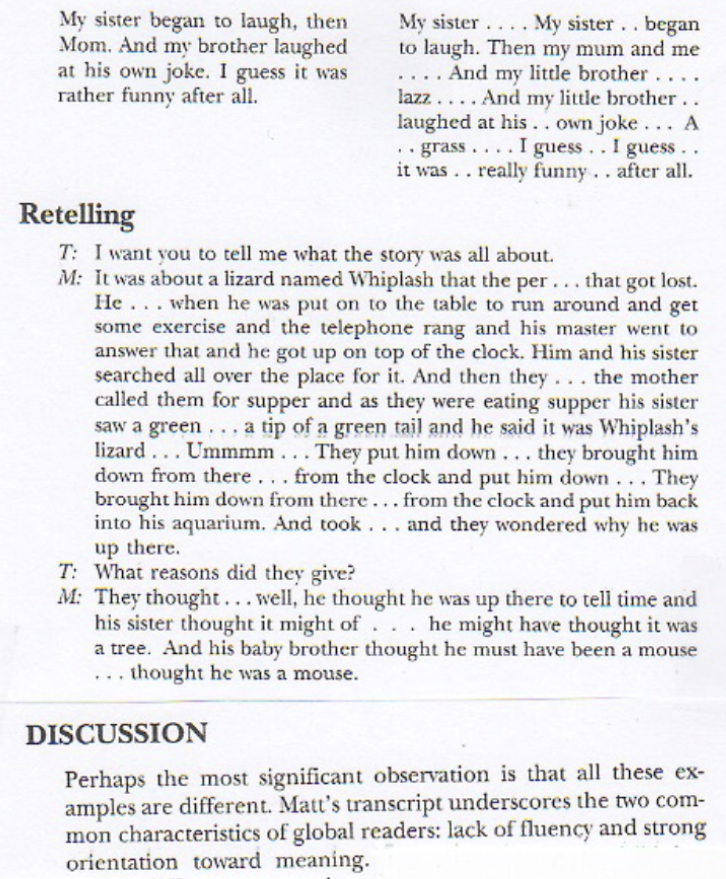

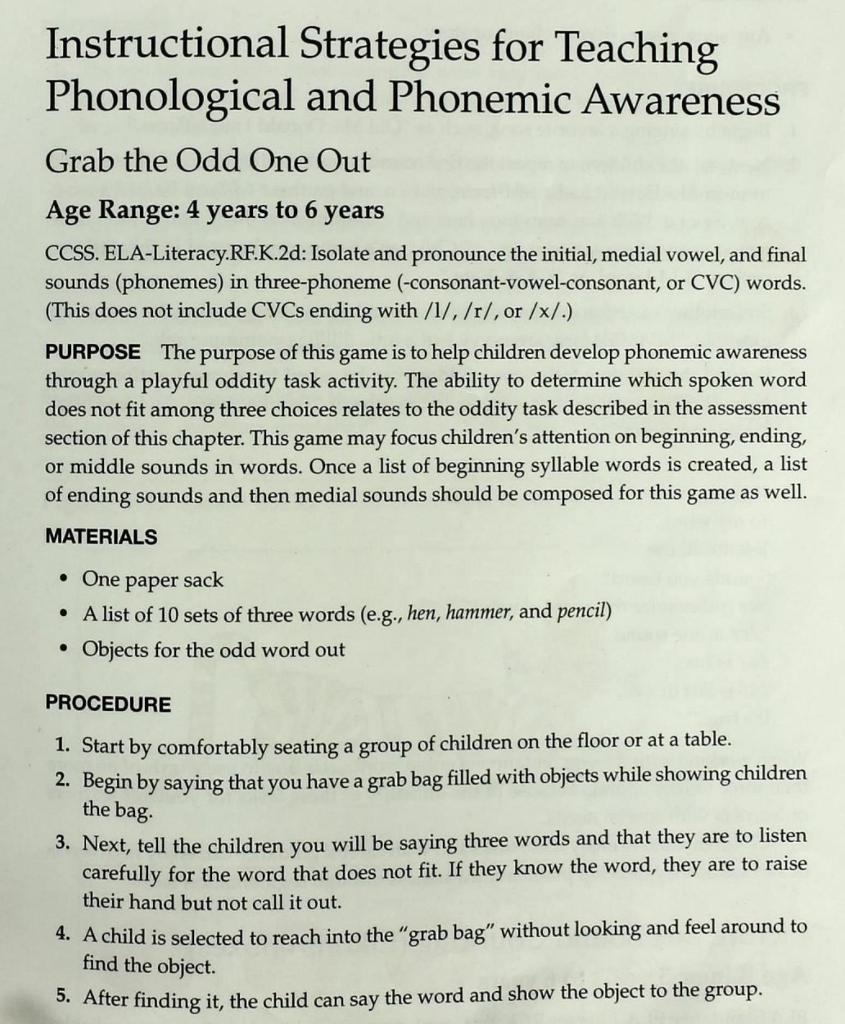

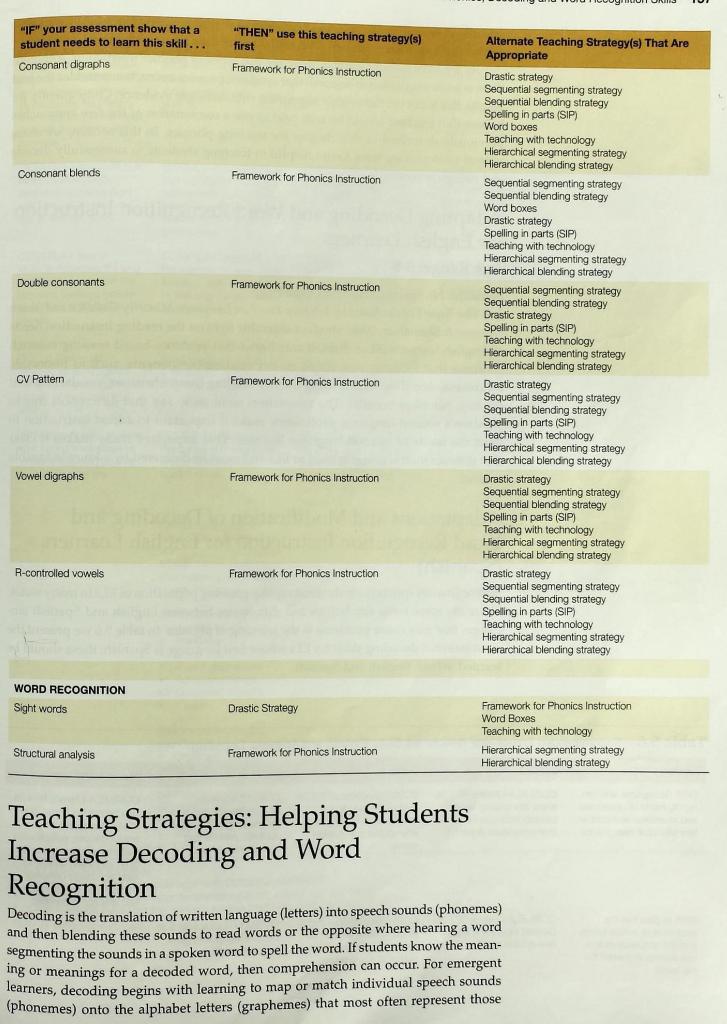

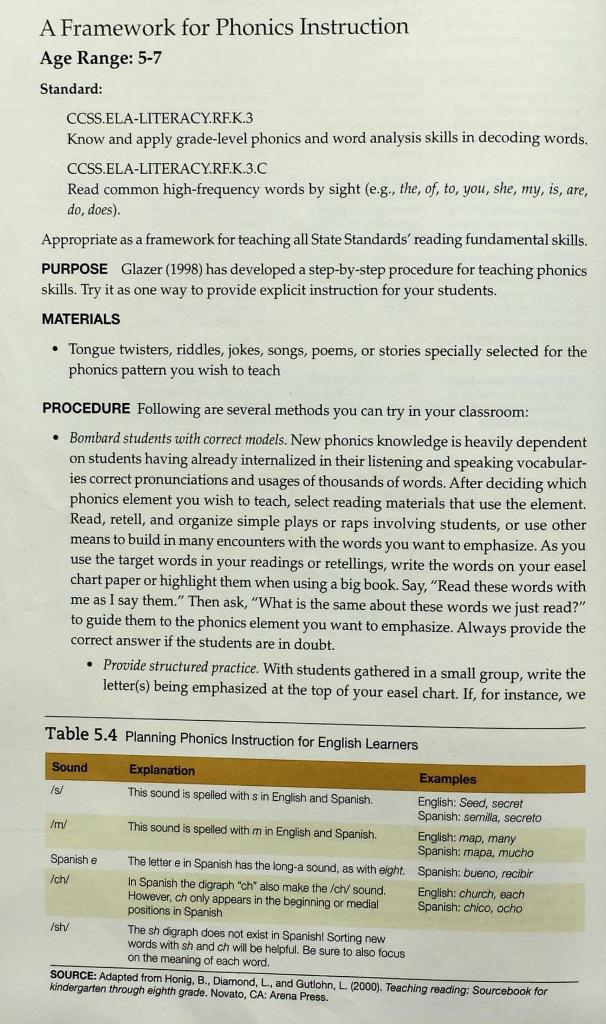

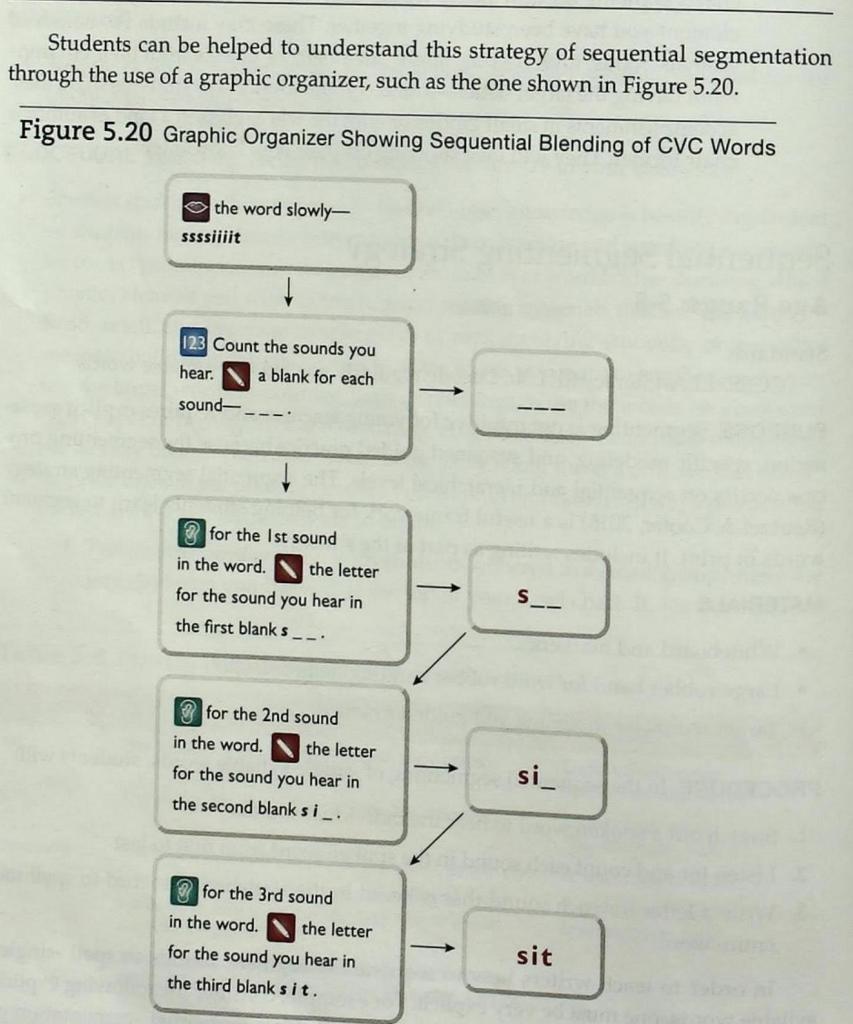

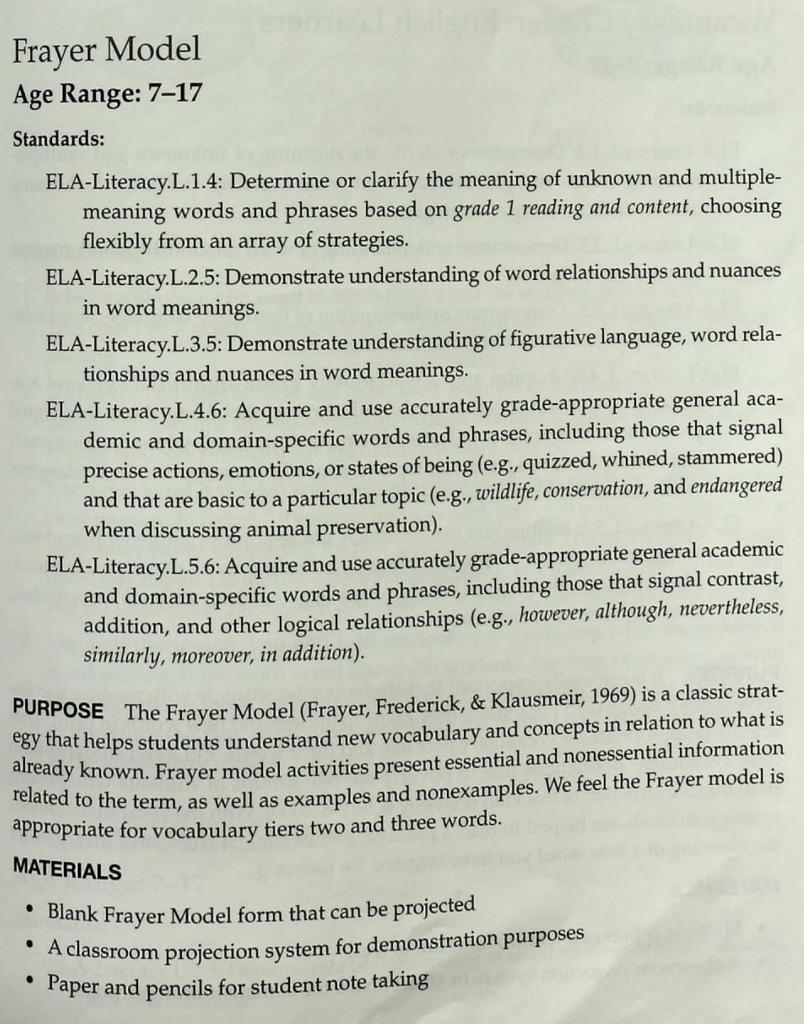

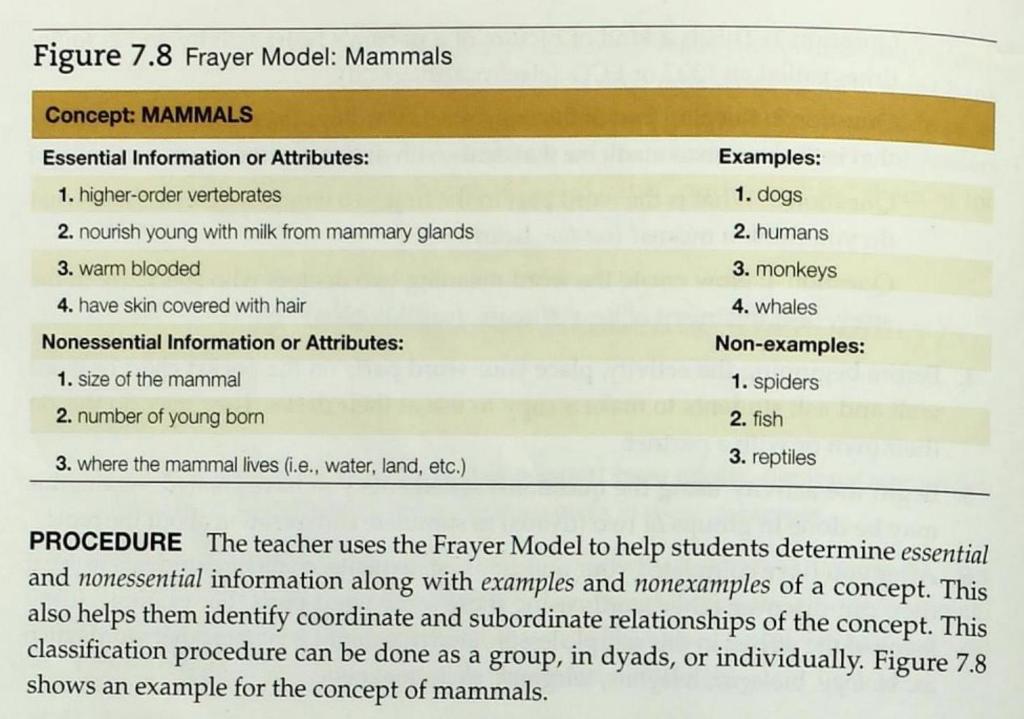

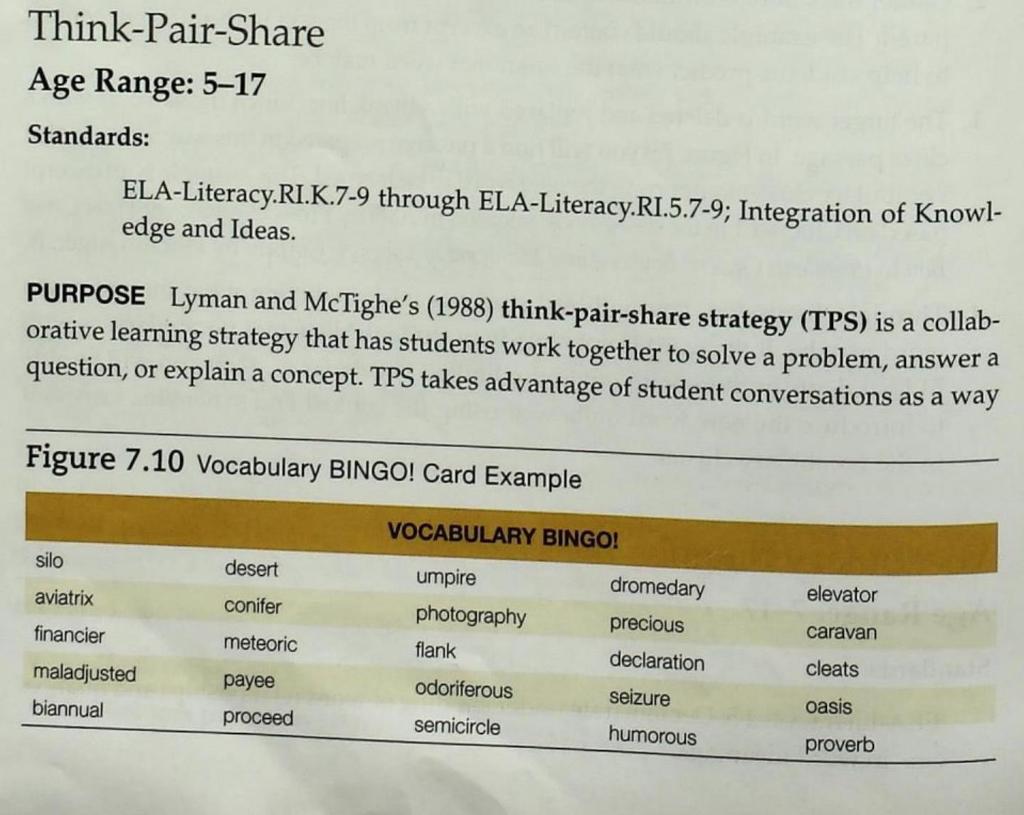

Matt, Casey's brother, was 12 years old at this reading. He had earlier repeated grade one and was now just finishing his second year in grade five. A standard readiness program in his kindergarten had been followed by two years of very strictly sequenced phonemic segmentation in grade one, taught by experienced teachers. The school had then revised its language arts program with a more holistically oriented basal, one that emphasized context and sight-word building along with phonics. Daily recovery work started during Matt's second year in grade one and continued throughout his elementary years. Matt's father was above average in his non-verbal abilities but didn't read at all, despite periodic efforts throughout his adult life to learn. Matt was within the normal range in non-verbal ability. Matt's reading of "Whiplash Escapes," from Evaluation Resource Book for Grade Two (Courtney, 1979) was part of the endof-year assessment session, so he hadn't seen the material, although he was familiar with this type of session. I told him the title and subject: a pet lizard that got into trouble, and instructed him to "do the best you can" without help. The story is a mid grade two readability. A reader fluent at this level takes between one and a half and two minutes to read this passage. Matt took 11 minutes, seven seconds. Two dots between words indicate word-by-word reading, four mean a longer pause, none shows normal fluency. I hope that seeing the complete transcript in this manner will give you the visual equivalent of what it sounded like, as well as demonstrate how Matt's "chunking" of words increased as he proceeded through the passage. I have also included a miscuecoded version of the passage to give a better idea of his overall use of strategies. (See page 124 for translation of codes used.) Note particularly his frequent corrections and use of rerun. Misue-coded version Whiplash is my green tree lizard. He's arl/linteresting pet, but not everybody in our family yijkes)him.Mylittle brother doesn't like him becauselone day Whiplash ate his/guppies. My mom says Whiplash is/fine as long as he stays in the aquarium. But sometimes) when Momlisn't around I take Whiplash out of the aquarium. I let him run around on the kitchen table. That's what he was doing last Saturday when the phone rang. I left him for just a minute while the phone it. When the looked all over the kitchen but 2 couldn't find him. Mom came into the kitcheno "What are you looking for, Randy?" she asked. "Oh, nothing, Mom," I said. ( couldn't tell her that Whiplash was missing. Then I ran to find my sister Al- always ..also.. Anne fison. She helped me look for Whiplash, but we couldn't find him anywhere in the house. We had to give up when **t (1. Sat and looked at my plate, but I couldn't eat.) Just re-directed then Allison poked me. "Look up there," she whispered. I looked up. Right on top of the grandfather'slock, I saw (9) a tail * the tip of a greer//il. Mmmm... mmm.. What's the lizard's name? T : You can make one up if you'd like. Mm... I can't think of one. T: OK. Keep going. Plootoo. One day... 81 That UMum jumped "There's Whiplashl" I cried. Mom reached up and took him down from the clock. She put him back in the aquarium, ("Now how did you think said "Now why do you think he went up there?" she asked. "Maybe he thought the clock was a tree," said Allison. "After all, he is a tree lizard." "Maybe he wanted to find out what time it was," I said. "Maybe he thinks he's a mouse," said my little brother. My sister began to laugh, T my Mum asd me Gittle My sister began to laugh, then Mome And my, brother, laughed at his own joke. (lg griess it was rather funny after all. $4 Maybe he... Maybe he thought... What's that word? [pointing to clock] Longhand version. T: You do the best you can. [fouse] ... thought the clock was a tree Text Matt Whiplash is my green tree Whiplash... is... a.. green...tree lizard. He's an interesting pet, .. lizard... Had....He's .. but not everybody in our fami- an. . . in .... insect... pet.. ly likes him. My little brother but ... but.... not .. everybody doesn't like him because one.. in ... . out family ... Like .. day Whiplash ate his guppies. him ... My .... My .... little.. My mom says Whiplash is fine brother. . doesn't like .. him beas long as he stays in the cause... I... day... one day aquarium. ....Mmmmmm .... mmmm .... What's the little lizard's namc? [Teacher: You can make one up for him if you'd like. Matt: Mmmm ... I can't think of one. Teacher: O.K. Keep going. Matt: Plootoo] One day ..... Whiplash .. ate .. his.... gup .... gept .... Mum .. said.. Whiplash .. is . Whiplash is . . . fine . . as .. long ... as .. he stays .. in his .. aquarium. I sat and looked at my plate, but Just then .. Annie spotted him. I couldn't eat. Just then, Allison [Teacher: You skipped this senpoked me. "Look up there," she tence. Matt: Oh!] . . . I . sat . . whispered. I looked up. Right and looked .. at .. my . plate .. on top of the grandfather's but can't eat... Just then Annie clock, I saw the tip of a green spotted him... "Look up...there" tail. .. she . . whispered ... I . looked up... Right ... on top of .. the grandfather clock.. I saw a . . tail of . . a green ... t ....t. ai . . 1 .... I seen a .... top ... tip .. of a greentail. "There's Whiplash!" I cried. "That.. Whiplash .... Igood exMom reached up and took him pression] There's Whiplash!" .. I down from the clock. She put cried... Mum jumped.... Mum him back in the aquarium. reached up .. and .. took .. him ., down , from the clock... She .. put him .. back in .. the aquarium. "Now why do you think he went "Now why ... did you .... think up there?" she asked. .... Now how did you .... think he .. went up there?" .... "Now why did you think he went up there?" .. she said. "Maybc he thought the clock "Maybe he.... Maybe he thought was a tree," said Allison. "After .... [pointing to clock] What's that all, he is a tree lizard." word? [Teacher: You do the best you can.] .... thought the . . clock .. was a tree," . . he .... said Annie ... "After all . he . . is . . a .. tree lizard. Maybe he wanted to find out "Maybe .. he .. wanted .. to .. what time it was," I said. find . . out . . what time. . it was" . I said. "Maybe he thinks he's a mouse," My . ... Maybe he . . thought . said my little brother. thinks . . he .... thinks his .. he's a mouse" . said my little brother. But sometimes when Mom isn't But . . sometime . . when .. Mum around I take Whiplash out of is not . . . isn't .. around . . I the aquarium. I let him run take .. Whiplash .. out of .. the around on the kitchen table. .. aquarium...I .. let him .. run That's what he was doing last around... on...the.. kitchen Saturday when the phone rang. . fl .... table ... That's . what I left him for just a minute while he . . was . . doing . . like .... I answered it. When I came last... S ... Saturday .. when back, Whiplash was gone. I the .. telephone rang.... I . . left looked all over the kitchen but I him .... left . . him .. for . . just couldn't find him. a . . minute ... wheel ... while.. I . . answered the phone .... while I answered it.... while? ... yeah . . . Then the .... When . I . . came back. . Whiplash . . was . . gone ... I .. looked .. all over .. the . kitchen . but . . I . couldn't find him. Mom came into the kitchen. Mum came into .. the kitchen.. "What are you looking for, with all..." What are you.. lookRandy?" she asked. ing for ....R . . Robert?" she said . she asked. "Oh, nothing, Mom," I said. I [With good expression] "Oh, couldn't tell her that Whiplash nothing, Mum." I .. said ... was missing. Then I ran to find Couldn't . tell her . . that my sister Allison. She helped Whiplash . was . . . was . . . me look for Whiplash, but we missing ... Then I .. ran . . to couldn't find him anywhere in find my .. sis .. sister .... all the house. We had to give up always also .... Annie when Mom called the three of ... She .. helped .. me .. lovk.. us for supper. for .. Whiplash . . but . we . . could .... couldn't . find . . him anywheres... In the house... We went for .... We .. had .. a .. good .... We ... had .. gave up . when Mum called .. the three of . . the three of .. use ... for supper us for supper. I sat and looked at my plate, but Just then .. Annie spotted him. I couldn't eat. Just then, Allison [Teacher: You skipped this senpoked me. "Look up there," she tence. Matt: Oh!] . . . I . sat . . whispered. I looked up. Right and looked .. at .. my . plate .. on top of the grandfather's but can't eat... Just then Annie clock, I saw the tip of a green spotted him... "Look up...there" tail. .. she . . whispered ... I . looked up... Right ... on top of .. the grandfather clock.. I saw a . . tail of . . a green ... t ....t. ai . . 1 .... I seen a .... top ... tip .. of a greentail. "There's Whiplash!" I cried. "That.. Whiplash .... Igood exMom reached up and took him pression] There's Whiplash!" .. I down from the clock. She put cried... Mum jumped.... Mum him back in the aquarium. reached up .. and .. took .. him ., down , from the clock... She .. put him .. back in .. the aquarium. "Now why do you think he went "Now why ... did you .... think up there?" she asked. .... Now how did you .... think he .. went up there?" .... "Now why did you think he went up there?" .. she said. "Maybc he thought the clock "Maybe he.... Maybe he thought was a tree," said Allison. "After .... [pointing to clock] What's that all, he is a tree lizard." word? [Teacher: You do the best you can.] .... thought the . . clock .. was a tree," . . he .... said Annie ... "After all . he . . is . . a .. tree lizard. Maybe he wanted to find out "Maybe .. he .. wanted .. to .. what time it was," I said. find . . out . . what time. . it was" . I said. "Maybe he thinks he's a mouse," My . ... Maybe he . . thought . said my little brother. thinks . . he .... thinks his .. he's a mouse" . said my little brother. My sister began to laugh, then My sister.... My sister .. began Mom. And my brother laughed to laugh. Then my mum and me at his own joke. I guess it was . And my little brother.... rather funny after all. lazz... . And my little brother .. laughed at his .. own joke ... A . grass.... I guess... I guess.. it was .. really funny .. after all. Reteling T: I want you to tell me what the story was all about. M: It was about a lizard named Whiplash that the per ... that got lost. He ... when he was put on to the table to run around and get some exercise and the telephone rang and his master went to answer that and he got up on top of the clock. Him and his sister searched all over the place for it. And then they ... the mother called them for supper and as they were eating supper his sister saw a green ... a tip of a green tail and he said it was Whiplash's lizard... Ummmm ... They put him down ... they brought him down from there ... from the clock and put him down .... They brought him down from there... from the clock and put him back into his aquarium. And took... and they wondered why he was up there. T : What reasons did they give? M: They thought... well, he thought he was up there to tell time and his sister thought it might of ... he might have thought it was a tree. And his baby brother thought he must have been a mouse ... thought he was a mouse. DISCUSSION Perhaps the most significant observation is that all these examples are different. Matt's transcript underscores the two common characteristics of global readers: lack of fluency and strong orientation toward meaning. Instructional Strategies for Teaching Phonological and Phonemic Awareness Grab the Odd One Out Age Range: 4 years to 6 years CCSS. ELA-Literacy.RF.K.2d: Isolate and pronounce the initial, medial vowel, and final sounds (phonemes) in three-phoneme (-consonant-vowel-consonant, or CVC) words. (This does not include CVCs ending with /1/,/r/, or /x/.) PURPOSE The purpose of this game is to help children develop phonemic awareness through a playful oddity task activity. The ability to determine which spoken word does not fit among three choices relates to the oddity task described in the assessment section of this chapter. This game may focus children's attention on beginning, ending, or middle sounds in words. Once a list of beginning syllable words is created, a list of ending sounds and then medial sounds should be composed for this game as well. MATERIALS - One paper sack - A list of 10 sets of three words (e.g., hen, hammer, and pencil) - Objects for the odd word out PROCEDURE 1. Start by comfortably seating a group of children on the floor or at a table. 2. Begin by saying that you have a grab bag filled with objects while showing children the bag. 3. Next, tell the children you will be saying three words and that they are to listen carefully for the word that does not fit. If they know the word, they are to raise their hand but not call it out. 4. A child is selected to reach into the "grab bag" without looking and feel around to find the object. 5. After finding it, the child can say the word and show the object to the group. 6. When an object has been used, it is returned to the grab bag for use with the next set of words. 7. This process continues until all the objects in the grab bag have been used. Instructional Strategies for Teaching Letter Name Knowledge The Sounds Rhythm Band Age Range: 5-7 Standards: ELA-Literacy.RF.K.2d: Isolate and pronounce the initial, medial vowel, a final sounds (phonemes) in three-phoneme (-consonant-vowel-consonant, or CV words. (This does not include CVCs ending with /1///r/, or /x/.) CCSS.-ELA-Literacy.RF.1.2d: Segment spoken single-syllable words into their cos plete sequence of individual sounds (phonemes). PURPOSE The tapping task developed by Liberman and colleagues (1974) is the ba for the sounds rhythm band activity. Using this activity, children learn to hear soun in words in sequence. This is a critical prerequisite for blending sounds together make words in reading and for segmenting words into sounds for writing and spe ing words. MATERIALS - A list of 5 to 10 words containing two, three, or four sounds PROCEDURE 1. This activity uses different rhythm band instruments to tap out the number of sounds in spoken words. Rhythm band instruments include sticks, bells, tambourines, metal triangles, and so on that can be used to make a noise for each sound heard in a word. Begin by modeling a word very slowly while striking the rhythm band instrument for each letter or sound, progressing sound by sound (cat). 2. After an initial demonstration, encourage the children to join in the activity by saying the next word with the teacher while striking their instruments for each sound they hear. 3. The teacher gradually releases responsibility to the children by exchanging roles. For example, the teacher can pronounce the word and the children strike the number of sounds they hear on their instruments. Or conversely, the children say the word slowly and the teacher strikes the number of sounds she hears on her instrument. 4. Finally, the children both say the word slowly and strike their instruments for each sound they hear in the word. We suggest this activity begin as a choral activity with all the children participating together. Individual children are then asked to perform solo, saying a word and striking the sounds he or she hears in a word. Eventually, children should be able to count the number of sounds in a word and be able to answer questions about the order of sounds in words (Griffith \& Olson, 1992). Instructional Strategies for Helping Students Learn Concepts about Print After a thorough assessment of a student's knowledge of the concepts about print, one or more of the following instructional strategies may be appropriately applied in subsequent teaching. Perhaps the most important thing for teachers to remember is that students with poorly developed print concepts benefit greatly from being immersed in a multitude of print-related activities in print-rich classroom environments (Venn \& Jahn, 2004). Authentic reading and writing experiences coupled with the informed guidance of a caring teacher or other literate individuals (e.g., parents, peers, and volunteers) can do much to help students learn necessary print concepts. Reutzel, Oda, and Moore (1989) found that implicit teaching of concepts about print is as effective or more effective than explicit instruction. This means that the concepts about print instructional strategies we are about to describe are best employed when they are embedded in the actual act of reading a text. For example, pointing to print in a left to right direction while reading aloud from an enlarged print displayed on computer screen is an implicit instruction strategy for demonstrating the concept of print known as print directionality. Verbal Punctuation Age Range: 5 years to 6 years ELA Standards: ELA-Literacy.RF.K.1 and CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RF.1.1: Demonstrate understanding of the organization and basic features of print. PURPOSE Drawing students' attention to punctuation is often difficult for both students and teachers. Nonetheless, taking note of punctuation is important for students to achieve reading fluency and comprehension. Students who ignore punctuation often read without proper phrasing, rate, or intonation, which in turn interrupts comprehension. Students who skip or miss punctuation marks often run sentences together, resulting in confused or broken comprehension. The purpose of the verbal punctuation strategy is to help students notice punctuation in a playful and engaging fashion, a strategy first made famous by the comedian Victor Borge. MATERIALS - An enlarged text that has been previously read and shared by the students and teacher together during a read aloud PROCEDURE 1. The verbal punctuation concepts about print instruction strategy is a process in which each punctuation mark in a piece of text is given a sound when encountered in a read aloud. For example, making the raspberry sound may represent a period. When a question mark comes up, a rising "uh" sound can be made. 2. This process continues, giving a sound to each punctuation mark found in a text. 3. Once all punctuation marks have been assigned a sound, the teacher may read aloud the first few sentences, modeling for students how to make the sounds for each punctuation mark as a part of the oral rereading. 4. Having modeled the process, students join in the rereading of the text, making the sounds for each punctuation mark in the text. Children find this strategy highly engaging and will continue its use spontaneously on later occasions; fortunately, the effect wanes over time, and this strategy has by this time served its eye-attracting, humorous, and engaging purpose. A lesson plan for teaching concepts about print using verbal punctuation is found in the sample lesson below. Sample Lesson: Teaching Print Concepts Using Verbal Punctuation - Teach this lesson to a K or 1st grade student or small group of students. Note two things: 1) the level of motivation the strategy engenders, and 2) the attention students pay to punctuation marks in print as a result. Lesson Objective Students will represent the punctuation marks in the text, The Gingerbread Man, with various verbal sounds and hand gestures to draw attention to punctuation marks as found in an enlarged text during a shared reading experience. Supplies - Enlarged text in a big book or a traditional book enlarged with a document camera or an online or audio version of the book projected onto a screen or smart board for shared reading. - Simple pointer for tracking print as an enlarged text is read by the group, - Highlighter tape or erasable markers for highlighting punctuation as an enlarged text is read by the group Explanation When we read, authors provide marks on the page to help us know when to take breaks, read certain words or parts of the text louder, change the pitch in our voice from low to high or high to low, and stop. These marks are called punctuation marks. I will show you a page of print from a familiar story we have read before - The Gingerbread Man. In this story, on the first page we see several punctuation marks. Highlight using highlighter tape or circle using an erasable marker on the enlarged print page the punctuations marks. Today, we are going to read this story again together. But when we see two types of punctuation marks we are going to do two things. First we are going to make a sound for that punctuation mark and second we are going to make a sign with our hands for that punctuation mark. The two punctuation marks we are looking for today are a period and a comma. A period is a black dot (point to one in the print, then write a period on the board). The second punctuation mark we are looking for today is the common. A comma is a black dot with a little tail (point to one in the print, then write a comma on the board). When we see a period in the story today as we read, we are going to make a "raspberry" sound like this (demonstrate) and take our finger and poke it out once like this (demonstrate). When we see a comma in the story today as we read, we are going to make a "growling" sound like this (demonstrate) and take our finger and poke it out once and make a little tail like this (demonstrate). Let me show you how this will sound and look. Read the first two pages of the book The Gingerbread Man making sounds and hand gestures for periods and commas. Participation After demonstrating, invite children to join in with you in a unison shared reading of the remaining pages of The Gingerbread Man. Use a pointer to help children track the enlarged print as a group and stop at each period and comma circling the punctuation marks of periods and commas with the pointer and inviting students to make the appropriate sound(s) and the hand gesture(s). Connecting Assessment Findings to Teaching Strategies Before discussing phonics and decoding teaching strategies, we provide an If-Then Chart connecting assessment findings to intervention and strategy choices (see Figure 5.19). It is our intention to help you select the most appropriate instructional interventions and strategies to meet your students' needs based on assessment data. In the next part of this chapter, we offer instruction strategies for interventions based on the foregoing assessments. Teaching Strategies: Helping Students Increase Decoding and Word Recognition Decoding is the translation of written language (letters) into speech sounds (phonemes) and then blending these sounds to read words or the opposite where hearing a word segmenting the sounds in a spoken word to spell the word. If students know the meaning or meanings for a decoded word, then comprehension can occur. For emergent learners, decoding begins with learning to map or match individual speech sounds (phonemes) onto the alphabet letters (graphemes) that most often represent those sounds. Research by Byrne (2013) suggests that explicit instruction in phonics and applying phonics knowledge is preferred when teaching young children to decode. As we have already learned, there are five types of phonics instruction. Although there is some suggestion in research that synthetic phonics instruction provides the best results, this is not yet thoroughly supported with sufficient evidence. Consequently we believe that teachers would be well paid to use a combination of the five approaches previously described in this chapter for teaching phonics. In this section, we share several strategies we have found helpful in teaching students to successfully decode and recognize words. Adapting Decoding and Word Recognition Instruction for English Learners Age Range: 5-8 Standard: No Specific Standard Offered The Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language Minority Children and Youth (August \& Shanahan, 2006) shed considerable light on the reading instruction needs of English learners (ELs). First, it was found that evidence-based reading research confirms that focusing instruction on key reading components, such as phonemic awareness, decoding, oral reading fluency, reading comprehension, vocabulary, and writing, has clear benefits. The researchers went on to say that differences due to children's second-language proficiency make it important to adjust instruction to meet the needs of -second-language learners. This important study makes it clear that phonics instruction is critical to ELs and must be delivered by a knowledgeable teacher. Adaptations and Modification of Decoding and Word Recognition Instruction for English Learners (Spanish) Native Spanish speakers are the most rapidly growing population of ELs in many states. There are some basic similarities and differences between English and Spanish languages that may cause problems in the learning of phonics. In table 5.6 we present the most essential decoding skills for ELs whose first language is Spanish; these should be learned in both English and Spanish. A Framework for Phonics Instruction Age Range: 5-7 Standard: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RF.K.3 Know and apply grade-level phonics and word analysis skills in decoding words. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RF.K.3.C Read common high-frequency words by sight (e.g., the, of, to, you, she, my, is, are, do, does). Appropriate as a framework for teaching all State Standards' reading fundamental skills. PURPOSE Glazer (1998) has developed a step-by-step procedure for teaching phonics skills. Try it as one way to provide explicit instruction for your students. MATERIALS - Tongue twisters, riddles, jokes, songs, poems, or stories specially selected for the phonics pattern you wish to teach PROCEDURE Following are several methods you can try in your classroom: - Bombard students with correct models. New phonics knowledge is heavily dependent on students having already internalized in their listening and speaking vocabularies correct pronunciations and usages of thousands of words. After deciding which phonics element you wish to teach, select reading materials that use the element. Read, retell, and organize simple plays or raps involving students, or use other means to build in many encounters with the words you want to emphasize. As you use the target words in your readings or retellings, write the words on your easel chart paper or highlight them when using a big book. Say, "Read these words with me as I say them." Then ask, "What is the same about these words we just read?" to guide them to the phonics element you want to emphasize. Always provide the correct answer if the students are in doubt. - Provide structured practice. With students gathered in a small group, write the letter(s) being emphasized at the top of your easel chart. If, for instance, we Table 5.4 Planning Phonics Instruction for English Learners kincergarten through eighth grade. Novato, CA: Arena Press. are emphasizing the consonant digraph ch, the following words can be written and said aloud slowly by the teacher: cheese, church, cherry. Then students are encouraged to contribute others having that same beginning sound (perhaps chain, change, charm, child). - Assess learning using a phonics game. The object of this game is to assess student learning by matching the letter or letter combination being emphasized with pictures representing words beginning with that sound. Cut a sheet of tagboard into several pieces about flash card size. Create cards for each student showing the letter or sound being studied. Collect several pictures of objects or creatures from magazines whose names begin with that letter or sound. Place students into pairs. Then demonstrate to students how to cut and paste pictures from magazines onto the tagboard cards showing the beginning sound you are emphasizing. Repeat the exercise, except this time students are doing the task with you in their groups of two (i.e., finding pictures of objects or creatures whose names begin with the specified sound). Check the products from each group with the students. Ask them to name the picture that begins with that sound. - Sharing what they have learned. Children love to share (and brag about) their accomplishments. Help them create word banks, pocket dictionaries, or word charts showing off how many words they can find containing the phonics element you have been studying together. These may include the names of animals, foods, toys, friends, family members, or objects from their environment having the target-letter-sound combination. Have students share their accomplishments in small groups or with the whole class in a kind of author's chair format. They will love showing off their new knowledge! Students can be helped to understand this strategy of sequential segmentation through the use of a graphic oroanizer swch se tho ons chavirn in D: D..... =20. Modeling: Today we are going to learn a strategy for spelling single syllable words and how to check to see if we spelled the words correctly. Listen to the word - stop. Now say the word scope aloud. Next say the word stop slowly and count the number of sounds you hear. Draw a line for each sound you hear - The first sound is /s/. The letter that represents the first sound /s/ is s. The second sound is /t/. The letter that represents the second sound /t/ is t. The third sound is /o/. The letter that represents the third sound /0/ is o. The fourth and final sound is /p/. The letter that represents the fourth or final sound /0/ is p. So we have spelled the word stop. Which of these look like the word stop. Guided Practice: "Let's practice together segmenting some sounds of letters in words to say words." I will model for you how to segment the sounds of letters in words. Here is a word, sled. I want to segment the sounds of the letters to say the word. To segment the letter sounds in this word I begin by stretching the word out and counting each sound I hear in the word s le d=4. I draw four lines on my paper for each sound I hear . . . . I think to myself, this is the sound /s/ and I know that the letter represents this sound /s/ is s. So, I write s in the first blank. Next, think to yourself, this is the sound /// and I know that the letter represents this sound I/ is I. So, I write I in the second blank. Next, I think to myself, this is the sound /e/ and I know that the letter represents this sound /e/ is e. So, I write e in the third blank. Finally, think to yourself, this is the sound /d/ and I know that the letter represents this sound / d/ is d. So, I write d in the fourth or final blank. So we have spelled the word sled. Which of these look like the word sled. slop sled stop Continue guided practice over several days using at least six words per day gradually sharing away the steps of segmenting with the group. Then move this process into small groups segmenting cvc and (cb)cvc words together for several more days before asking individual students to segment the letter sounds together to say words. Independent Practice Now, you will segment the letter sounds to spell words on your own. Here is a list of 10 initial consonant blend one-syllable words to show me how you can use the sequential segmenting process to pronounce these words. Let's begin with the first word on the list: Strap Slip Blank Flip Pray Trip Grape Skate Play Fry Developing Reading Fluency for Each Student After a careful assessment of a student's reading fluency as outlined previously, one or more of the following fluency development strategies or integrated fluency lesson frameworks may be appropriately applied. Perhaps the most important thing to remember is that children with poorly developed fluency must receive regular opportunities to read and reread for authentic and motivating reasons, such as to gather information, to present a dramatization, or simply to reread a favorite story. The strategies described in this section offer effective and varied means to help learners become more fluent readers in authentic, effective, and motivating ways. Fluency-Oriented Reading Instruction Age Range: 6 years 12 years Standard: ELA-Literacy.RF.1.4 through CCSS. ELA-Literacy.RF 5.4: Read with sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension. PURPOSE Fluency-oriented reading instruction (FORI), based on repeated reading research, is an integrated lesson framework for providing comprehensive instruction and practice in fluency in the elementary school (Stahl, Heubach, \& Cramond, 1997). FORI consists of three interlocking aspects, according to its authors: (1) a redesigned core reading program lesson, (2) a buddy-reading period at school, and (3) a home reading program. Recent research on the effects of FORI showed that children receiving FORI instruction significantly outperformed a control group comparison (Kuhn \& Schwanenflugel, 2008; Stahl \& Heubach, 2006; Stahl et al., 2003). MATERIALS - Core reading program text - Richly appointed classroom library for free reading at school and home - Extension activities drawn from the core reading program text - Teacher-prepared graphic organizer of the text in the core or basal program - Teacher-prepared audio for assisted reading practice PROCEDURE On the first day of a FORI lesson: 1. The teacher begins by reading the core reading program story or text aloud to the class. 2. Following the reading by the teacher, the students and teacher interactively discuss the text to place reading comprehension up front as an important goal to be achieved in reading any text. 3. Following this discussion, the teacher teaches vocabulary words and uses graphic organizers and other comprehension activities focused around the story or text the teacher has read aloud. On the second day of a FORI lesson: 1. Teachers can choose to have children echo read the core reading program text with the teacher or have children read only a part of the story repeatedly for practice with a partner or with the teacher. 2. Following this practice session, the story or text is sent home for the child to read with parents, older siblings, or other caregivers. On the third and fourth days of a FORI lesson: 1. Children receive additional practice. 2. Children then participate in vocabulary and comprehension exercises around the story. 3. Children are also given decoding instructions on difficult words in the core reading story or text. On the fifth and final day of the FORI lesson: 1. Children are asked to give a written response to the story to cement their comprehension of the text. In addition to the core reading program instruction to develop fluency found in the FORI framework, the teachers provide additional in-school free-reading practice with easy books that students read alone (if they are strong readers) or with partners (buddy reading) for between 15 and 30 minutes per day. At the beginning of the year, the time allocated to this portion of a FORI lesson is closer to 15 minutes; the time increases throughout the year to 30 minutes. As a part of their homework assignment in the FORI framework, children are expected to read at home 15 minutes a day at least 4 days per week. This outside reading is monitored through the use of reading logs. Explicit Fluency Instruction Age Range: 6 years 12 years Standard: ELA-Literacy.RF.1.4 through CCSS.-ELA- Literacy.RF 5.4: Read with sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension. PURPOSE The primary purposes of explicit fluency instruction are twofold: (1) to teach students to clearly understand what is meant by fluency, and (2) to teach students how to self-monitor, evaluate, self-regulate, and otherwise "fix up" their own fluency problems over time. "Some students struggle with reading because they lack information about what they are trying to do and how to do it. They look around at their fellow students who are learning to read [fluently and well] and say to themselves, 'How are they doing that?' In short they are mystified about how to do what other students seem to do with ease" (Duffy, 2004, p. 9). Age Range: 6 years 12 years Standard: ELA-Literacy.RF.2.4 through CCSS. ELA-Literacy.RF 5.4: Read with sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension. ELA-Literacy.RF.1.4 through CCSS. ELA-Literacy.RF 5.4: Read with sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension. PURPOSE Choral reading is one of the most commonly used research-based fluency development strategies (Paige, 2011). In many classrooms, students are asked to read aloud in a solo, barbershop, or round-robin fashion. However, note that roundrobin oral reading carries with it significant instructional, emotional, and psychological risks for all children, but most especially for struggling readers (Eldredge, Reutzel, \& Hollingsworth, 1996; Opitz \& Rasinski, 2008). Homan, Klesius, and Hite (1993) found that choral reading practice yields excellent gains in fluency and comprehension for all children. All choral reading strategies may be done in whole groups, small groups, and with students working in pairs. Echo reading can also be done between children and their parents at home. In the classroom, the same text may be used each time for four or five sessions in repeated reading, or you may decide to use a variety of texts. There are actually three choral reading strategies for teachers to choose from: unison, echo, and antiphonal. - Unison: The teacher and students read the same text passage together. - Echo: The teacher reads a passage aloud and then students repeat it. - Antiphonal: Derived from ancient monastic traditions, antiphonal reading involves two groups. The first reading group (or person, if they are reading in pairs) reads a section of a passage aloud (usually a sentence or two), and the second group reads the next section. The groups continue alternating passages in this way. MATERIALS - One copy of a passage from any text genre, including poetry, nonfiction (e.g., science, social studies), fiction, or even songs PROCEDURE For teachers who are new to using choral reading, Cooter (2009) has developed an implementation plan that may be used over the course of a week and only takes 5 to 10 minutes per day. This particular example is for use with core-content texts (e.g., science, social studies). This plan begins with unison reading and then expands into echo and antiphonal reading to provide variety. You will see that this plan uses explicit instruction elements as well as the gradual release of responsibility. PRETEACHING PREPARATIONS 1. Identify a unit of study (at least 1 to 2 weeks ahead in your curriculum). 2. Identify an important text selection of about 250 words you will use for whole-class choral reading. (Planning tip: Try using a chapter introduction or summary for this activity.) TEACHING STUDENTS HOW TO PARTICIPATE IN WHOLECLASS CHORAL READING STRATEGY STEPS: MONDAY 1. Introducing new words. Briefly review the correct pronunciations and meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to students. 2. Teacher modeling and first reading. Ask students to pay attention to how the teacher uses punctuation and phrasing (commas, question marks, etc.) for correct prosody or voice intonation while reading the selected passage aloud. Students are asked to read along silently from their copy of the text selection while the teacher is reading aloud. 3. Second reading. After completing Step 2 , inform students that they will begin reading aloud and in unison (the whole class together) and that they should start after the teacher counts down from 3. - Teacher then says "Begin reading in 3-2-1." - Teacher leads the students by reading aloud in a strong voice, being careful to read at a moderate speed so that everyone can keep up. - While reading aloud, the teacher should walk about the room to ensure that everyone is reading and should also listen for any words or phrases that students have difficulty with for possible reteaching (such as those reviewed in Step 1). 4. New word review. After the first whole-class reading, the teacher should review any ords or phrases with which students are having difficulty. 5. Third reading. The teacher explains to students that we will be reading the same text another time and that they should read a little louder this time because the teacher will be reading a little softer. The teacher begins the class reading with a 3-2-1 countdown and monitors class reading while walking the room. Strategy Steps: Tuesday through Friday - The same passage is to be read once each day by the whole class. - You may use echo or antiphonal reading on Wednesday through Friday, if desired. TEACHER EVALUATION: CHORAL READING Teachers, like students, go through stages of expertise development in the implementation of new teaching strategies. Cooter (2009) has developed a kind of rubric, or continuum, for implementing choral reading to help you monitor your own use of choral reading and discover ways to deepen its use in your classroom (see Figure 6.9). To add additional variety to choral reading, Karen Wood (1983) has suggested an approach for reading a story orally in a group. In four-way oral reading, the reading of a text should be varied by using four different types of oral reading: (1) unison choral reading, (2) echoic or imitative reading, (3) paired reading, and (4) mumble reading (Wood, 1983). All of these approaches to oral reading, except mumble reading, are described elsewhere in this chapter. Mumble reading, or reading quietly aloud, is typically heard among young readers as they are initially told to read silently. These young readers tend to "mumble" as they attempt to read silently. Teachers should model this approach to oral reading before asking students to mumble read (reading with a soft voice no one else can hear). Figure 6.9 Implementation Continuum for Whole-Class Choral Reading - Passages of about 250 worlds are selected from the adopted textbook. - The passage selected should be at least 1 to 3 weeks ahead of the teacher's curriculum. - The same passage is used each time for five consecutive days. Using Student Assessment Data to Guide Instruction: A Classroom Profile and an If-Then Teaching Strategy Guide After reviewing evidence-based research as well as the Common Core foundational skills for reading fluency, we constructed a classroom profile for your use to summarize vocabulary skill development for each student. In Table 7.3 we provide for your use our CLASSROOM PROFILE FORM: READING VOCABULARY LEARNING SKILLS Table 7.3 Classroom Profile Form: Reading Vocabulary Learning Skills \& Needs Connecting Assessment Findings to Teaching Strategies Before discussing fluency intervention strategies, we provide an If-Then Chart connecting assessment to intervention and strategy choices. It is our intention to help you select the most appropriate instructional interventions and strategies to meet your students' fluency development needs based on assessment data. Most fluency development activities tend to fall into differing types of practice strategies. In the If-Then Chart shown in Table 7.4 we have listed the teaching strategies that appear in the next section and link them to key areas of need that your fluency assessments have revealed. Teaching Strategies for Vocabulary Development There are four fundamental types of word learning around which vocabulary instruction is organized (Armbruster, Lehr, \& Osborn, 2008). First is helping students learn a new meaning for a known word. For example, students are well acquainted with the word "run" as a verb as in "moving about quickly" as opposed to walking. But the word run has some 645 different meanings depending on context and syntax. A few of these might include: Marvin had a run of bad luck; Mother did the school run today since it was her turn in the car pool; Jen had a run in her stocking; and Birch Avenue runs from the cobble stones down to the harbor. So, part of the teacher's job is to show how some words have multiple meanings. A second type of word learning involves learning the meaning of a new word for an already known concept. For example, students may understand that some things in life are relatively commonplace like McDonald's restaurants, soccer games, and schools. But they may not know that another word for things pervasive in everyday life is ubiquitous. The third type of vocabulary instruction has students learning the meaning of a new word or term for an unknown concept. As an example, a student may not know the term water cycle or the process it represents. This type of Tier 2 and Tier 3 vocabulary is common in the subject areas and is known as academic vocabulary (Picot, 2017). Academic vocabulary to be taught is typically identified in the adopted curriculum for each subject area (mathematics, science, social studies, English language arts). There are also resources you can tap online such as Coxhead's (2000) Academic Word List (AWL) available at vocabulary.com and other websites. Finally, clarifying and enriching the meaning of a known word is the fourth type of word learning. This often involves learning more subtle differences in words related to a similar concept. For example, a student may learn the differences between kayak, schooner, canoe, skiff, ferry, and outrigger when thinking about boats and their different purposes. The teaching strategies that follow may be used to satisfy one or more of these four types of word learning according to the needs of your students. There is no better place to start than with word walls because of their great flexibility of use and purpose. Age Range: 7-17 Standards: ELA-Literacy.L.1.4: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiplemeaning words and phrases based on grade 1 reading and content, choosing flexibly from an array of strategies. ELA-Literacy.L.2.5: Demonstrate understanding of word relationships and nuances in word meanings. ELA-Literacy.L.3.5: Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships and nuances in word meanings. ELA-Literacy.L.4.6: Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases, including those that signal precise actions, emotions, or states of being (e.g., quizzed, whined, stammered) and that are basic to a particular topic (e.g., wildlife, conservation, and endangered when discussing animal preservation). ELA-Literacy.L.5.6: Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases, including those that signal contrast, addition, and other logical relationships (e.g., however, although, nevertheless, similarly, moreover, in addition). PURPOSE The Frayer Model (Frayer, Frederick, \& Klausmeir, 1969) is a classic strategy that helps students understand new vocabulary and concepts in relation to what is already known. Frayer model activities present essential and nonessential information related to the term, as well as examples and nonexamples. We feel the Frayer model is appropriate for vocabulary tiers two and three words. MATERIALS - Blank Frayer Model form that can be projected - A classroom projection system for demonstration purposes - Paper and pencils for student note taking PROCEDURE The teacher uses the Frayer Model to help students determine essential and nonessential information along with examples and nonexamples of a concept. This also helps them identify coordinate and subordinate relationships of the concept. This classification procedure can be done as a group, in dyads, or individually. Figure 7.8 shows an example for the concept of mammals. Think-Pair-Share Age Range: 5-17 Standards: ELA-Literacy.RI.K.7-9 through ELA-Literacy.RI.5.7-9; Integration of Knowledge and Ideas. PURPOSE Lyman and McTighe's (1988) think-pair-share strategy (TPS) is a collaborative learning strategy that has students work together to solve a problem, answer a question, or explain a concept. TPS takes advantage of student conversations as a way of discovering word and passage meanings. It has students think about a posed question and possible answers, pair with a classmate to compare their answers and decide on a final response, and then share their conclusions in a group conversation about the question. This strategy may be used before, during, or after reading a text. MATERIALS - A poster that describes the expectations and processes of the think-pair-share strategy, as shown in Figure 7.11. PROCEDURE 1. The process begins with the teacher instructing students to listen to a question or problem that uses one or more important vocabulary Tier 2 or 3 words. Example: In a study of government in a fifth grade class, the teacher has introduced several Latin (L) and Greek (G) roots including -archy (G. meaning "leader, first"), -cracy (G. meaning "rule, ruler"), gyn (o)-(L. meaning "woman, female"), and ro(G. meaning "man") and dem (o)-(G. meaning "the people"). 2. The teacher poses this question: "Using what you know about word parts, what do you think is the meaning of the word gynecocracy? When you think you know the answer that question, please give an example of a gynecocracy. You have three minutes to think of your responses." 3. Think. Students are given time to think of a response. 4. Pair. Students are asked to share their responses with a peer (i.e., an "elbow partner"). 5. Share. Finally, students are encouraged to share their responses with the whole group. A time limit is typically set for each segment of the think-pair-share strategy. By the way, in this example the word gynecocracy, when broken down into its roots-gyne- (woman) and -ocracy (rule), yields a meaning along the lines of "government by women" or "political supremacy of women." The Amazons would be one ancient example of a gynecocracy. of test or procedure scores including reliability and/or validity evidence. Few classroom-based informational text comprehension assessments report evidence of reliability or validity. Connecting Assessment Findings to Informational Text: Comprehension Instructional Strategies After reviewing evidence-based research as well as the Common Core foundational skills for reading, we can now construct a concise list of benchmark skills that should be learned by typically developing learners. These are the skills teachers must assess and develop a classroom profile indicating which skills should be taught to which learners in small group "targeted" instruction. In Table 9.1 we provide our CLASSROOM PROFILE FORM: COMPREHENSION OF INFORMATIONAL TEXT. Table 9.1 New Classroom Profile Form: Comprehending Informational Text CLASSROOM PROFILE FORM: INFORMATIONAL TEXT COMPREHENSION SKILLS -PARTIAL 4TH GRADE EXAMPLE Directions: First, in the upper box for each student, indicate for each student their level of attainment for each skill area using the key below (E, D, P). Second, record specific observations in the lower box that support your decision as to the student's level of development. TIP: For identifying students needing the same level of instruction at a glance, you may choose to color code each level of development, if you choose (e.g., green for P, yellow for developing, pink for emergent). Below is an example. Connecting Assessment Findings to Teaching Strategies Before discussing comprehension strategies for informational texts, we provide an If-Then Chart connecting assessment findings to intervention and strategy choices (see Figure 9.19). It is our intention to help you select the most appropriate instructional interventions and strategies to meet your students' needs based on assessment data. In the next part of this chapter, we offer instruction strategies for interventions based on the foregoing assessments. Strategies for Teaching Comprehension of Informational Texts Focusing on the Reader In addition to the RAND Reading Study Group's (2002) report and the National Read Panel (2000), the Institute of Education Sciences/What Works Clearinghouse Practice Guides (Kamil et al., 2008; Shanahan et al., 2010) have also weighed in on comprehension strategies and instructional practices affecting the reader. In what follows, we discuss a variety of strategies and procedures teachers and students can use to promote increased student background knowledge, use of background knowledge in comprehending informational texts, and student engagement. We address strategies that build reader engagement, background knowledge, comprehension monitoring, and social collaboration. Multiple Strategy Instruction Reciprocal Teaching Age Range: 5-12 Standard: CCSS.-ELA-Literacy.RI.K.1-9 through CCSS.-ELA-Literacy.RI.51-9: Key Ideas and Details, Craft and Structure, Integration of Knowledge and Ideas PURPOSE Palincsar and Brown (1985) designed and evaluated an approach for improving the reading comprehension and comprehension monitoring of students with special needs who scored two years below grade level on standardized tests of reading comprehension. Their results suggested a teaching strategy called reciprocal teaching that is useful for helping students who have difficulties with comprehension and comprehension monitoring, as well as those who are learning English (Casanave, 1988; Johnson-Glenberg, 2000; Rosenshine \& Meister, 1994). Although reciprocal teaching was originally intended for use with expository text, we can see no reason why this intervention strategy cannot be used with narrative texts by focusing discussion and reading on the major elements of stories. MATERIALS - A trade book, basal reader, or textbook selection - A poster displaying the four comprehension strategies and what they mean: predicting, questioning, summarizing, and clarifying PROCEDURE Essentially, this multiple-strategy lesson requires that teachers and students exchange roles, which is intended to increase student involvement in the lesson. The reciprocal teaching lesson comprises four phases or steps (Meyers, 2005; Oczkus, 2004): 1. Prediction. Students predict from the title and pictures the possible content of the text. The teacher records the predictions. 2. Question generation. Students generate purpose questions after reading a predetermined segment of the text, such as a paragraph, page, or section. 3. Summarizing. Students write a brief summary (see previous section) for the text by starting with "This paragraph was about..." Summarizing helps students capture the gist of the text. 4. Clarifying. Students and teacher discuss various reasons a text may be hard or confusing, such as difficult vocabulary, poor text organization, unfamiliar content, or lack of cohesion. Students are then instructed in a variety of comprehension fix-up or repair strategies. When teachers have modeled this process with several segments of text, the teacher assigns one of the students (preferably a good student) to assume the role of teacher for the next segment of text. The teacher may also, while acting in the student role, provide appropriate prompts and feedback when necessary. When the next segment of text is completed, the "teacher" assigns another student to assume that role. Teachers who use reciprocal teaching to help students with comprehension difficulties should follow four simple guidelines suggested by Palincsar and Brown (1985). 1. Assess student difficulties and provide reading materials appropriate to students' decoding abilities. 2. Use reciprocal teaching for at least 30 minutes a day for 15 to 20 consecutive days. 3. Model frequently and provide corrective feedback. 4. Monitor student progress regularly and individually to determine whether the instruction is having the intended effect. Palincsar and Brown reported positive results for this intervention procedure by demonstrating dramatic changes in students' ineffective reading behaviors. Other research has demonstrated the effectiveness of reciprocal teaching with a variety of students (Casanave, 1988; Johnson-Glenberg, 2000; Kelly, Moore, \& Tuck, 1994; King \& Parent-Johnson, 1999; Pressley \& Wharton-McDonald, 1997; Rosenshine \& Meister, 1994). Figure 9.28 Concept Oriented Reading Instruction Part I: Observe and Personalize 1. Hands-on experiences 2. Relate hands-on experience to prior experiences 3. Teacher-led discussion 4. Form theories 5. Generate questions for further study Part II: Search and Retrieve Teacher introduces search strategies for finding answers to their questions... 1. Goal setting (what they want to learn) 2. Categorizing (learning how information is organized and presented in books and how to find information in the library or on the Internet) 3. Extracting (taking notes, summarizing, and paraphrasing information) 4. Abstracting (forming generalizations) Part III: Comprehend and Integrate Teacher modeling and students' discussions about... 1. Comprehension monitoring (metacognition) 2. Developing images or graphics 3. Rereading to clarify 4. Modifying reading rate to match purpose and varying text types 5. Identification of central ideas and supporting details Part IV: Communication Communication of new knowledge through such media as... Debates Discussions Written reports Technology (e.g., Microsoft PowerPoint presentations) Poetry Dramas Raps or songs Graphic illustrations Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction Age Range: 7-12 Standard: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.K.1-3,7-

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts