Question: prepare graphs showing : (a) the daily output compared to design and effective capacity (b) cumulative output compared to cumulative design and effective capacity what

prepare graphs showing : (a) the daily output compared to design and effective capacity (b) cumulative output compared to cumulative design and effective capacity what do these tell us about the operation ?

prepare graphs showing : (a) the daily output compared to design and effective capacity (b) cumulative output compared to cumulative design and effective capacity what do these tell us about the operation ?

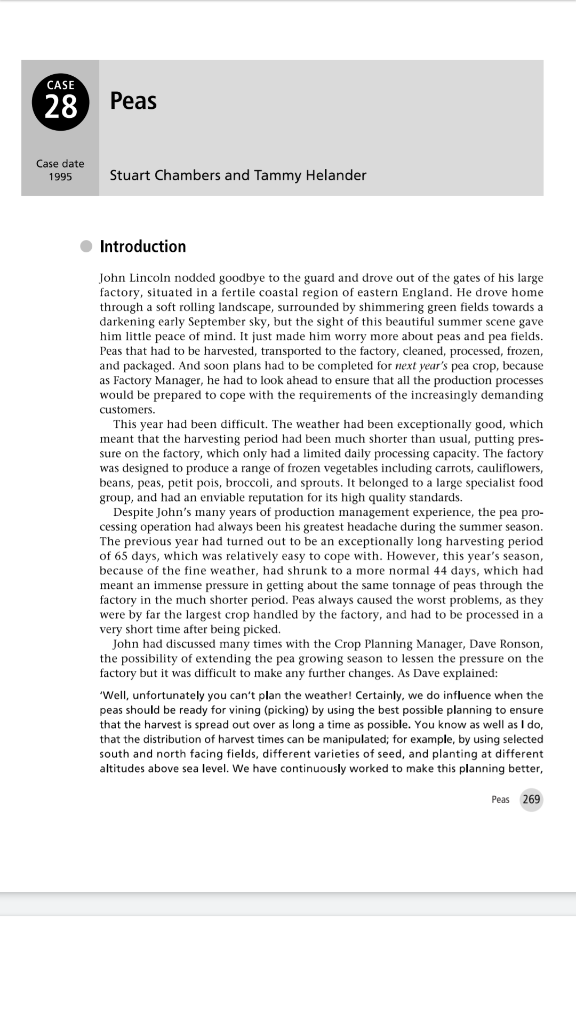

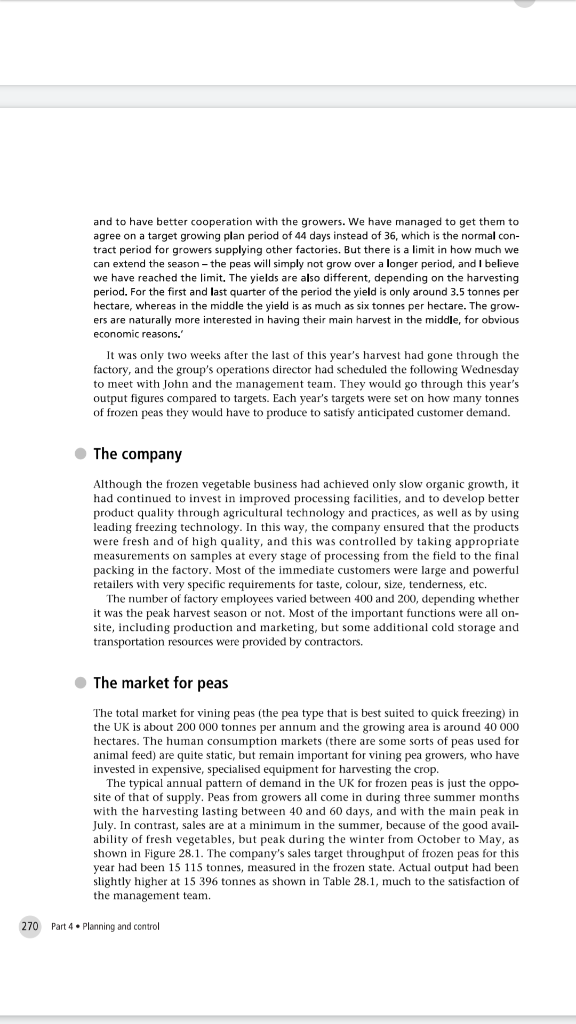

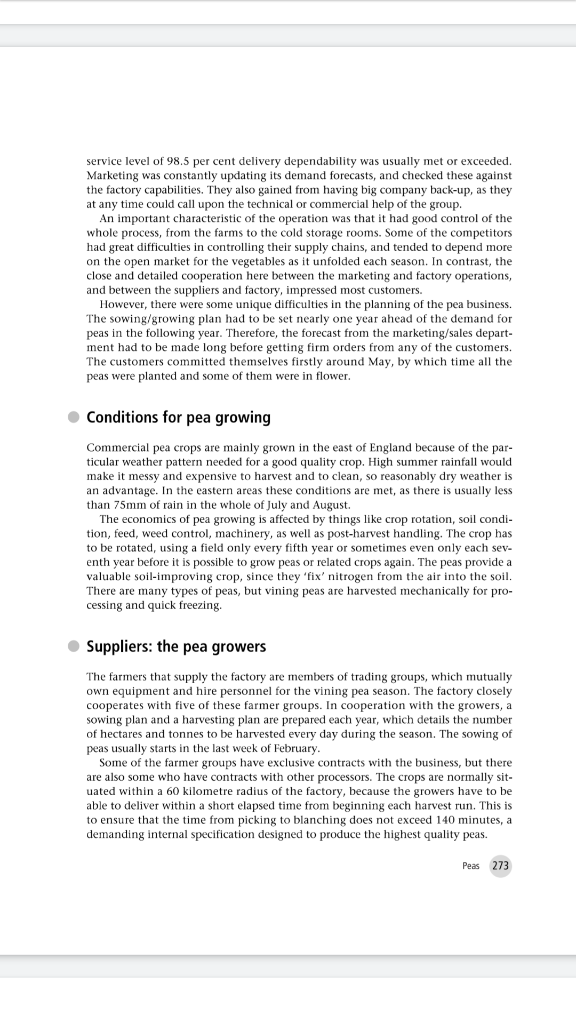

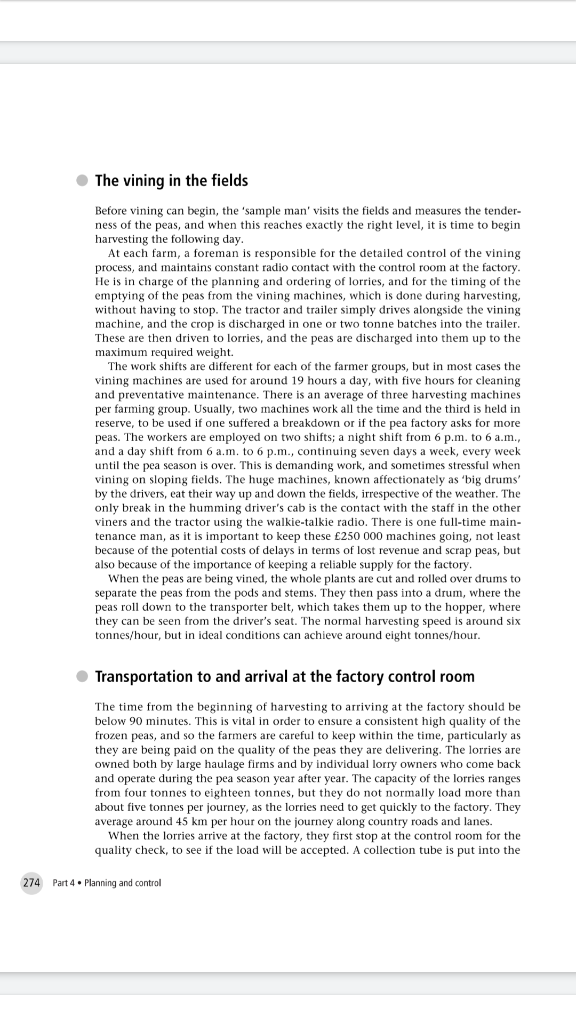

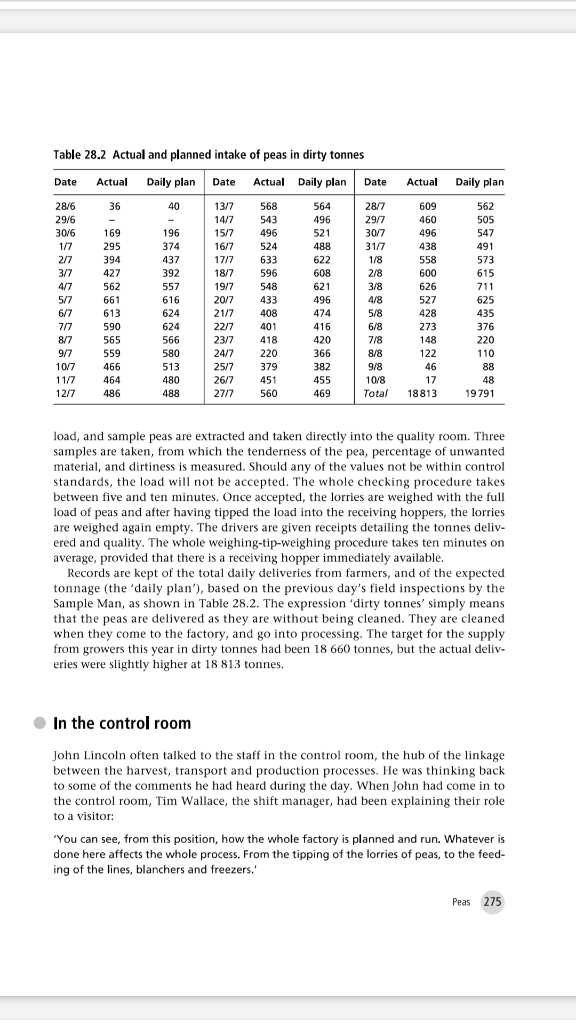

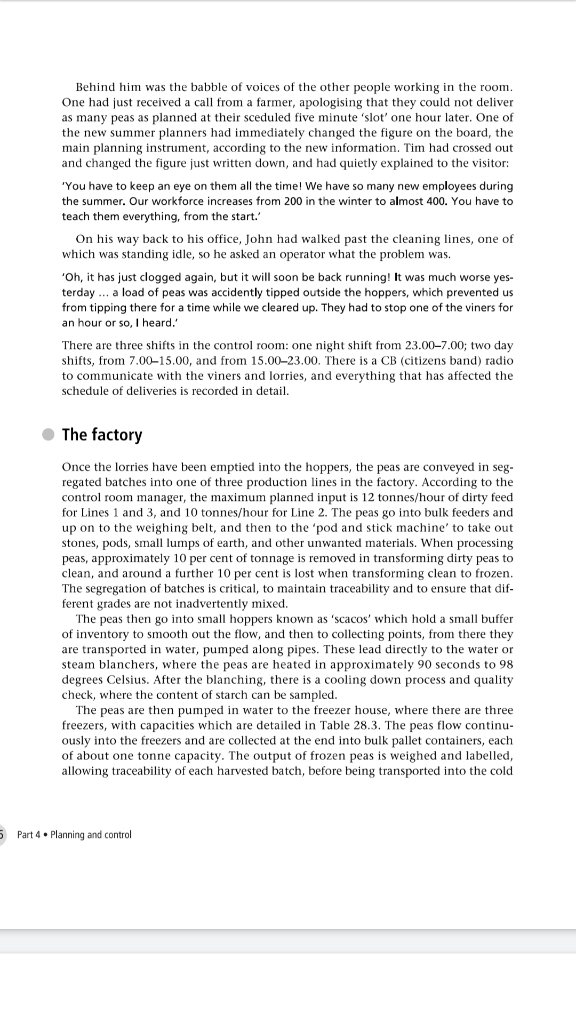

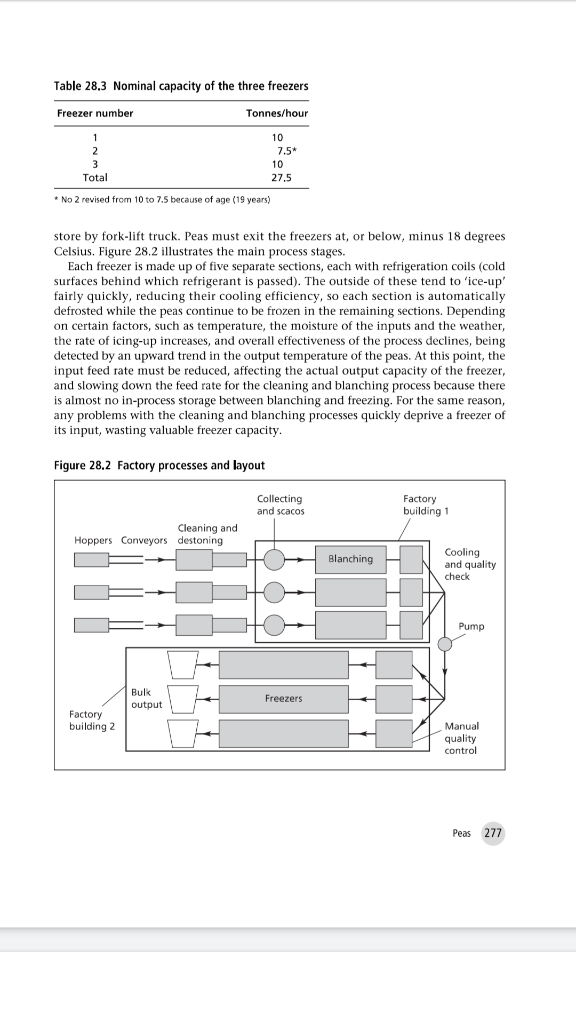

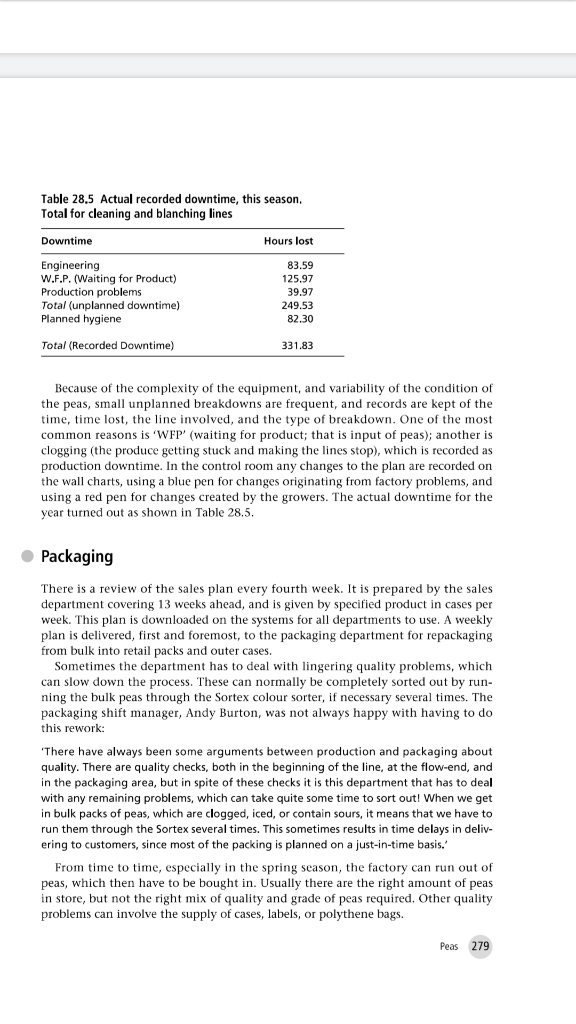

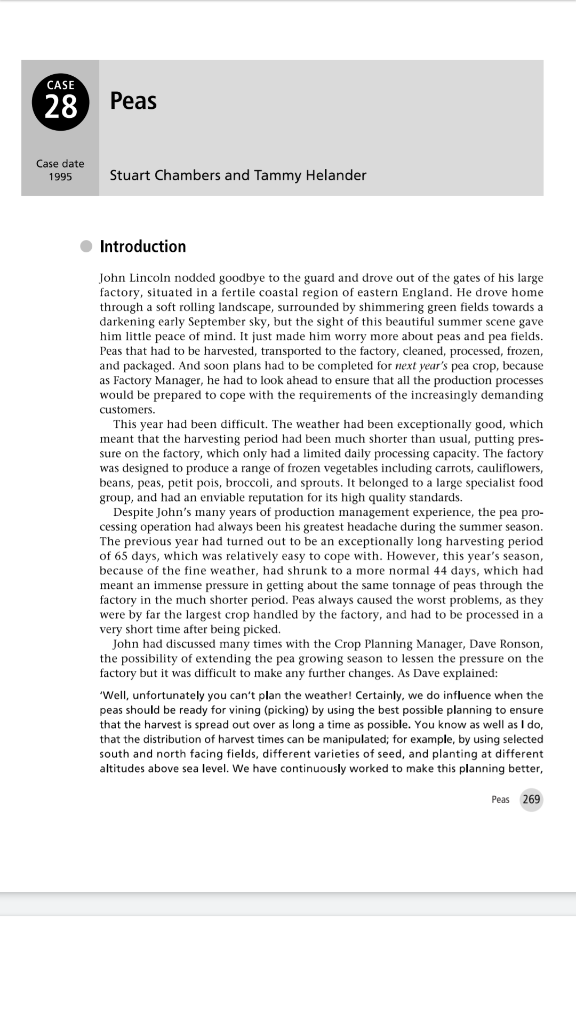

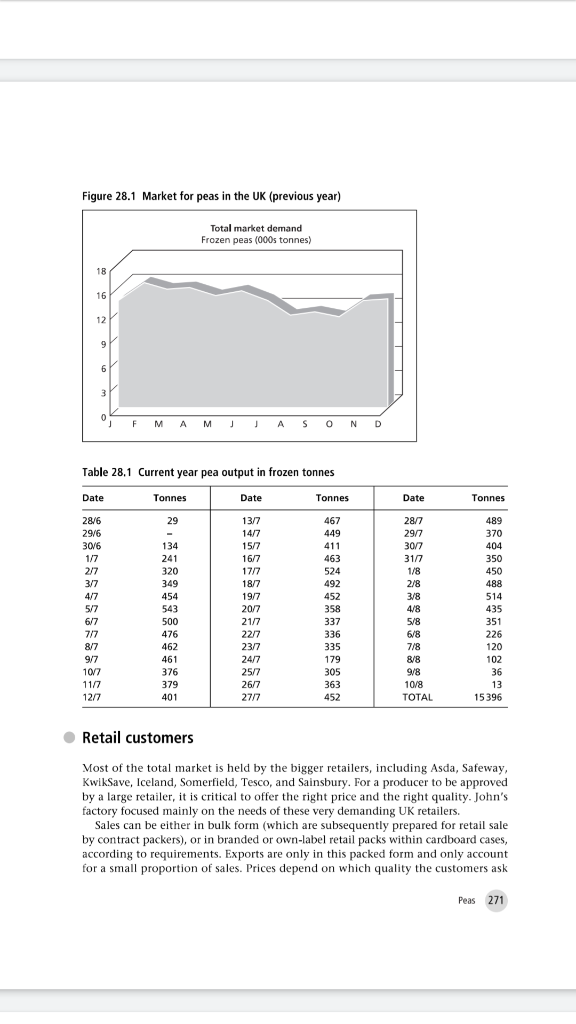

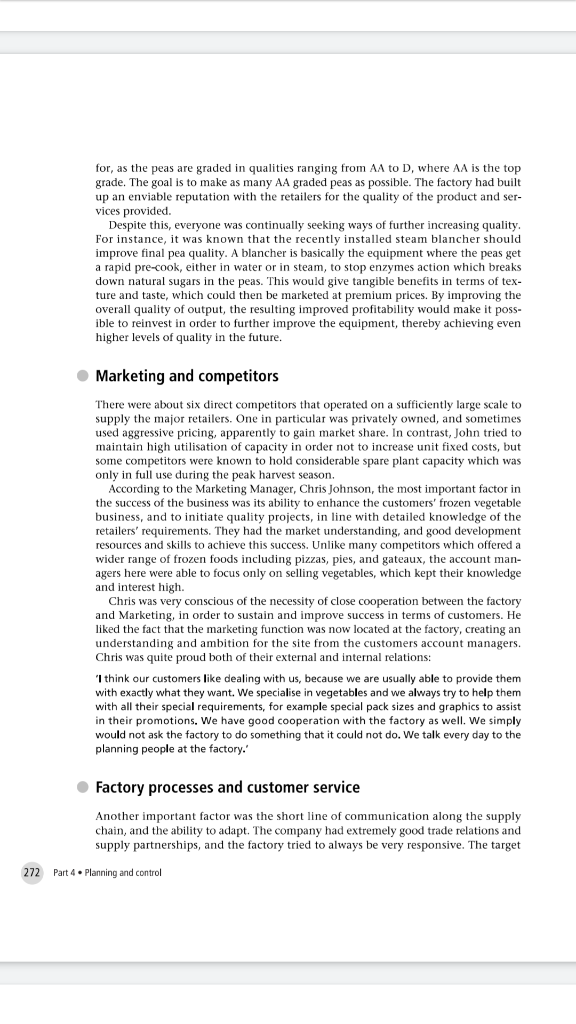

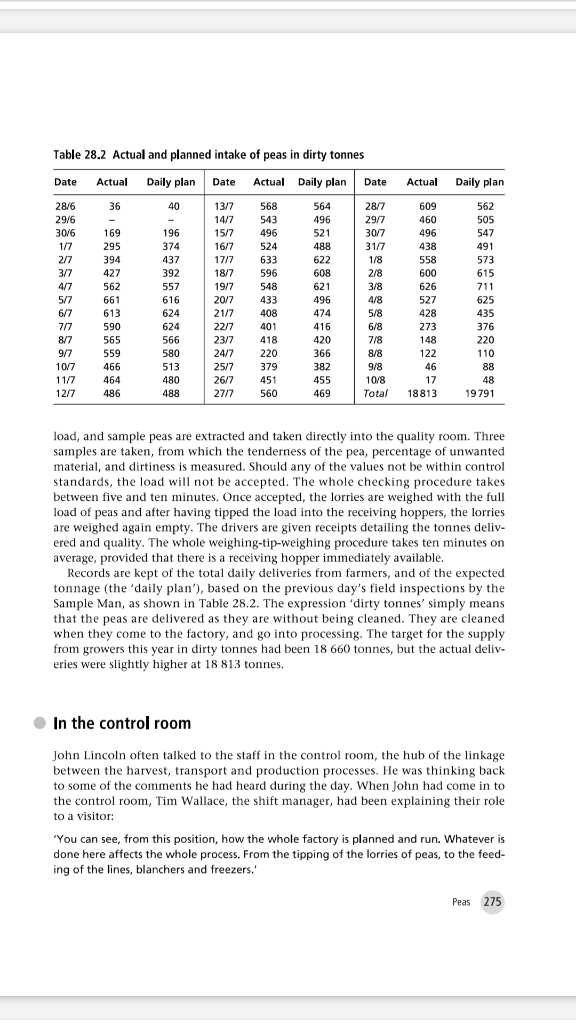

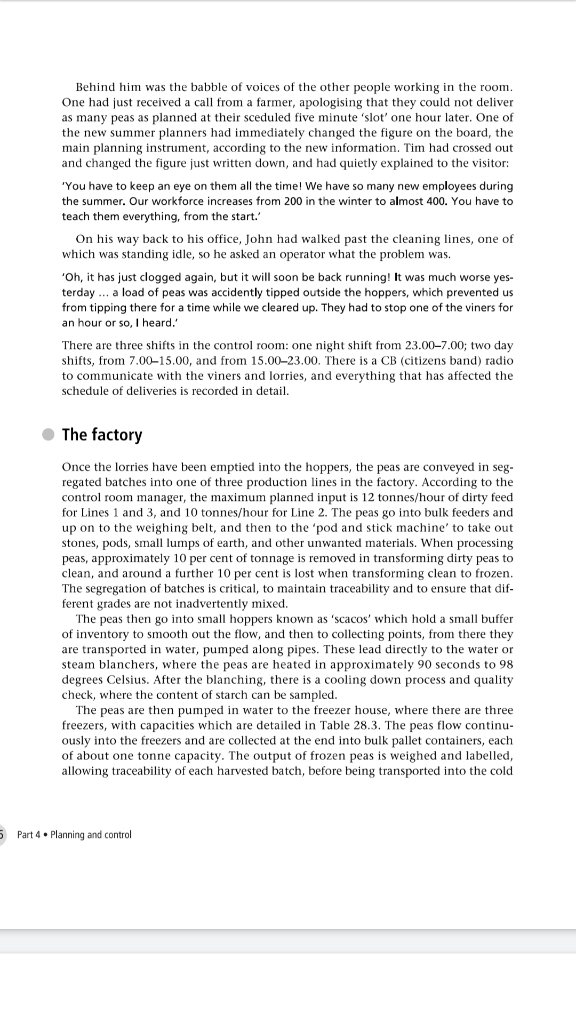

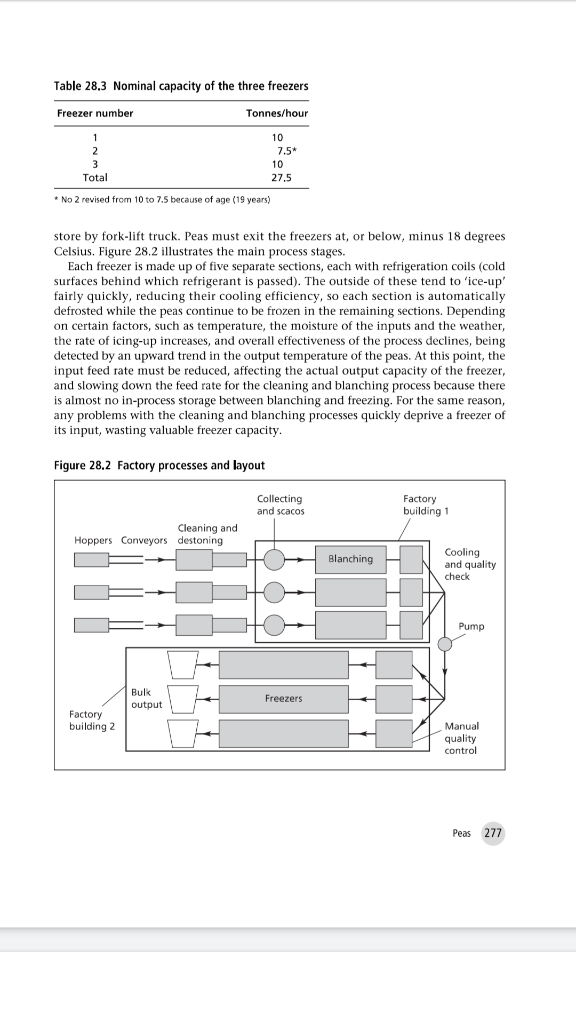

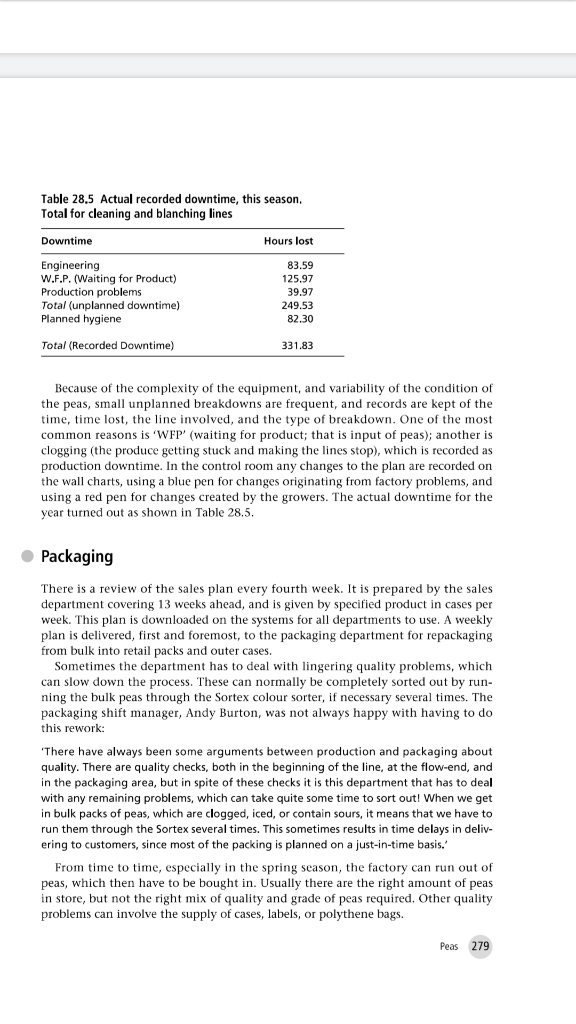

CASE 28 Peas Case date 1995 Stuart Chambers and Tammy Helander Introduction John Lincoln nodded goodbye to the guard and drove out of the gates of his large factory, situated in a fertile coastal region of eastern England. He drove home through a soft rolling landscape, surrounded by shimmering green fields towards a darkening early September sky, but the sight of this beautiful summer scene gave him little peace of mind. It just made him worry more about peas and pea fields. Peas that had to be harvested, transported to the factory, cleaned, processed, frozen, and packaged. And soon plans had to be completed for next year's pea crop, because as Factory Manager, he had to look ahead to ensure that all the production processes would be prepared to cope with the requirements of the increasingly demanding customers. This year had been difficult. The weather had been exceptionally good, which meant that the harvesting period had been much shorter than usual, putting pres- sure on the factory, which only had a limited daily processing capacity. The factory was designed to produce a range of frozen vegetables including carrots, cauliflowers, beans, peas, petit pois, broccoli, and sprouts. It belonged to a large specialist food group, and had an enviable reputation for its high quality standards. Despite John's many years of production management experience, the pea pro- cessing operation had always been his greatest headache during the summer season. The previous year had turned out to be an exceptionally long harvesting period of 65 days, which was relatively easy to cope with. However, this year's season, because of the fine weather, had shrunk to a more normal 44 days, which had meant an immense pressure in getting about the same tonnage of peas through the factory in the much shorter period. Peas always caused the worst problems, as they were by far the largest crop handled by the factory, and had to be processed in a very short time after being picked. John had discussed many times with the Crop Planning Manager, Dave Ronson, the possibility of extending the pea growing season to lessen the pressure on the factory but it was difficult to make any further changes. As Dave explained: 'Well, unfortunately you can't plan the weather! Certainly, we do influence when the peas should be ready for vining (picking) by using the best possible planning to ensure that the harvest is spread out over as long a time as possible. You know as well as I do, that the distribution of harvest times can be manipulated; for example, by using selected south and north facing fields, different varieties of seed, and planting at different altitudes above sea level. We have continuously worked to make this planning better, Peas 269 and to have better cooperation with the growers. We have managed to get them to agree on a target growing plan period of 44 days instead of 36, which is the normal con- tract period for growers supplying other factories. But there is a limit in how much we can extend the season - the peas will simply not grow over a longer period, and I believe we have reached the limit. The yields are also different, depending on the harvesting period. For the first and last quarter of the period the yield is only around 3.5 tonnes per hectare, whereas in the middle the yield is as much as six tonnes per hectare. The grow- ers are naturally more interested in having their main harvest in the middle, for obvious economic reasons.' It was only two weeks after the last of this year's harvest had gone through the factory, and the group's operations director had scheduled the following Wednesday to meet with John and the management team. They would go through this year's output figures compared to targets. Each year's targets were set on how many tonnes of frozen peas they would have to produce to satisfy anticipated customer demand. The company Although the frozen vegetable business had achieved only slow organic growth, it had continued to invest in improved processing facilities, and to develop better product quality through agricultural technology and practices, as well as by using leading freezing technology. In this way, the company ensured that the products were fresh and of high quality, and this was controlled by taking appropriate measurements on samples at every stage of processing from the field to the final packing in the factory. Most of the immediate customers were large and powerful retailers with very specific requirements for taste, colour, size, tenderness, etc. The number of factory employees varied between 400 and 200, depending whether it was the peak harvest season or not. Most of the important functions were all on- site, including production and marketing, but some additional cold storage and transportation resources were provided by contractors. The market for peas The total market for vining peas (the pea type that is best suited to quick freezing) in the UK is about 200 000 tonnes per annum and the growing area is around 40 000 hectares. The human consumption markets (there are some sorts of peas used for animal feed) are quite static, but remain important for vining pea growers, who have invested in expensive, specialised equipment for harvesting the crop. The typical annual pattern of demand in the UK for frozen peas is just the oppo- site of that of supply. Peas from growers all come in during three summer months with the harvesting lasting between 40 and 60 days, and with the main peak in July. In contrast, sales are at a minimum in the summer, because of the good avail- ability of fresh vegetables, but peak during the winter from October to May, as shown in Figure 28.1. The company's sales target throughput of frozen peas for this year had been 15 115 tonnes, measured in the frozen state. Actual output had been slightly higher at 15 396 tonnes as shown in Table 28.1, much to the satisfaction of the management team. 270 Part 4. Planning and control Figure 28.1 Market for peas in the UK (previous year) Total market demand Frozen peas (000s tonnes) 18 16 12 9 6 3 0 F M A M - J A s 0 0 0 Table 28.1 Current year pea output in frozen tonnes Date Tonnes Date Tonnes Date Tonnes 29 13/7 14/7 15/7 16/7 17/7 18/7 28/6 29/6 30/6 1/7 217 3/7 4/7 5/7 6/7 7/7 8/7 9/7 1007 11/7 12/7 134 241 320 349 454 543 500 476 462 461 376 379 401 19/7 20/7 21/7 22/7 23/7 24/7 25/7 26/7 27/7 467 449 411 463 524 492 452 358 337 336 335 179 305 363 452 28/7 29/7 30/7 31/7 1/8 2/8 3/8 4/8 5/8 6/8 7/8 8/8 9/8 10/8 TOTAL 489 370 404 350 450 488 514 435 351 226 120 102 36 13 15 396 Retail customers Most of the total market is held by the bigger retailers, including Asda, Safeway, KwikSave, Iceland, Somerfield, Tesco, and Sainsbury. For a producer to be approved by a large retailer, it is critical to offer the right price and the right quality. John's factory focused mainly on the needs of these very demanding UK retailers. Sales can be either in bulk form (which are subsequently prepared for retail sale by contract packers), or in branded or own-label retail packs within cardboard cases, according to requirements. Exports are only in this packed form and only account for a small proportion of sales. Prices depend on which quality the customers ask Peas 271 for, as the peas are graded in qualities ranging from AA to D, where AA is the top grade. The goal is to make as many AA graded peas as possible. The factory had built up an enviable reputation with the retailers for the quality of the product and ser- vices provided. Despite this, everyone was continually seeking ways of further increasing quality. For instance, it was known that the recently installed steam blancher should improve final pea quality. A blancher is basically the equipment where the peas get a rapid pre-cook, either in water or in steam, to stop enzymes action which breaks down natural sugars in the peas. This would give tangible benefits in terms of tex- ture and taste, which could then be marketed at premium prices. By improving the overall quality of output, the resulting improved profitability would make it poss- ible to reinvest in order to further improve the equipment, thereby achieving even higher levels of quality in the future. Marketing and competitors There were about six direct competitors that operated on a sufficiently large scale to supply the major retailers. One in particular was privately owned, and sometimes used aggressive pricing, apparently to gain market share. In contrast, John tried to maintain high utilisation of capacity in order not to increase unit fixed costs, but some competitors were known to hold considerable spare plant capacity which was only in full use during the peak harvest season, According to the Marketing Manager, Chris Johnson, the most important factor in the success of the business was its ability to enhance the customers' frozen vegetable business, and to initiate quality projects, in line with detailed knowledge of the retailers' requirements. They had the market understanding, and good development resources and skills to achieve this success. Unlike many competitors which offered a wider range of frozen foods including pizzas, pies, and gateaux, the account man- agers here were able to focus only on selling vegetables, which kept their knowledge and interest high Chris was very conscious of the necessity of close cooperation between the factory and Marketing, in order to sustain and improve success in terms of customers. He liked the fact that the marketing function was now located at the factory, creating an understanding and ambition for the site from the customers account managers. Chris was quite proud both of their external and internal relations: I think our customers like dealing with us, because we are usually able to provide them with exactly what they want. We specialise in vegetables and we always try to help them with all their special requirements, for example special pack sizes and graphics to assist in their promotions. We have good cooperation with the factory as well. We simply would not ask the factory to do something that it could not do. We talk every day to the planning people at the factory.' Factory processes and customer service Another important factor was the short line of communication along the supply chain, and the ability to adapt. The company had extremely good trade relations and supply partnerships, and the factory tried to always be very responsive. The target 272 Part 4. Planning and control service level of 98.5 per cent delivery dependability was usually met or exceeded. Marketing was constantly updating its demand forecasts, and checked these against the factory capabilities. They also gained from having big company back-up, as they at any time could call upon the technical or commercial help of the group. An important characteristic of the operation was that it had good control of the whole process, from the farms to the cold storage rooms. Some of the competitors had great difficulties in controlling their supply chains, and tended to depend more on the open market for the vegetables as it unfolded each season. In contrast, the close and detailed cooperation here between the marketing and factory operations, and between the suppliers and factory, impressed most customers. However, there were some unique difficulties in the planning of the pea business. The sowing/growing plan had to be set nearly one year ahead of the demand for peas in the following year. Therefore, the forecast from the marketing/sales depart- ment had to be made long before getting firm orders from any of the customers. The customers committed themselves firstly around May, by which time all the peas were planted and some of them were in flower, Conditions for pea growing Commercial pea crops are mainly grown in the east of England because of the par- ticular we needed for a quality . summ rainfall would make it messy and expensive to harvest and to clean, so reasonably dry weather is an advantage. In the eastern areas these conditions are met, as there is usually less than 75mm of rain in the whole of July and August. The economics of pea growing is affected by things like crop rotation, soil condi- tion, feed, weed control, machinery, as well as post-harvest handling. The crop has to be rotated, using a field only every fifth year or sometimes even only each sev- enth year before it is possible to grow peas or related crops again. The peas provide a valuable soil-improving crop, since they 'fix' nitrogen from the air into the soil. There are many types of peas, but vining peas are harvested mechanically for pro- cessing and quick freezing. Suppliers: the pea growers The farmers that supply the factory are members of trading groups, which mutually own equipment and hire personnel for the vining pea season. The factory closely cooperates with five of these farmer groups. In cooperation with the growers, a sowing plan and a harvesting plan are prepared each year, which details the number of hectares and tonnes to be harvested every day during the season. The sowing of peas usually starts in the last week of February Some of the farmer groups have exclusive contracts with the business, but there are also some who have contracts with other processors. The crops are normally sit- uated within a 60 kilometre radius of the factory, because the growers have to be able to deliver within a short elapsed time from beginning each harvest run. This is to ensure that the time from picking to blanching does not exceed 140 minutes, a demanding internal specification designed to produce the highest quality peas. Peas 273 The vining in the fields Before vining can begin, the 'sample man' visits the fields and measures the tender- ness of the peas, and when this reaches exactly the right level, it is time to begin harvesting the following day. At each farm, a foreman is responsible for the detailed control of the vining process, and maintains constant radio contact with the control room at the factory. He is in charge of the planning and ordering of lorries, and for the timing of the emptying of the peas from the vining machines, which is done during harvesting, without having to stop. The tractor and trailer simply drives alongside the vining machine, and the crop is discharged in one or two tonne batches into the trailer. These are then driven to lorries, and the peas are discharged into them up to the maximum required weight. The work shifts are different for each of the farmer groups, but in most cases the vining machines are used for around 19 hours a day, with five hours for cleaning and preventative maintenance. There is an average of three harvesting machines per farming group. Usually, two machines work all the time and the third is held in reserve, to be used if one suffered a breakdown or if the pea factory asks for more peas. The workers are employed on two shifts; a night shift from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., and a day shift from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., continuing seven days a week, every week until the pea season is over. This is demanding work, and sometimes stressful when vining on sloping fields. The huge machines, known affectionately as 'big drums' by the drivers, eat their way up and down the fields, irrespective of the weather. The only break in the humming driver's cab is the contact with the staff in the other viners and the tractor using the walkie-talkie radio. There is one full-time main- tenance man, as it is important to keep these 250 000 machines going, not least because of the potential costs of delays in terms of lost revenue and scrap peas, but also because of the importance of keeping a reliable supply for the factory, When the peas are being vined, the whole plants are cut and rolled over drums to separate the peas from the pods and stems. They then pass into a drum, where the peas roll down to the transporter belt, which takes them up to the hopper, where they can be seen from the driver's seat. The normal harvesting speed is around six tonnes/hour, but in ideal conditions can achieve around eight tonnes/hour. Transportation to and arrival at the factory control room The time from the beginning of harvesting to arriving at the factory should be below 90 minutes. This is vital in order to ensure a consistent high quality of the frozen peas, and so the farmers are careful to keep within the time, particularly as they are being paid on the quality of the peas they are delivering. The lorries are owned both by large haulage firms and by individual lorry owners who come back and operate during the pea season year after year. The capacity of the lorries ranges from four tonnes to eighteen tonnes, but they do not normally load more than about five tonnes per journey, as the lorries need to get quickly to the factory. They average around 45 km per hour on the journey along country roads and lanes. When the lorries arrive at the factory, they first stop at the control room for the quality check, to see if the load will be accepted. A collection tube is put into the 274 Part 4. Planning and control Table 28.2 Actual and planned intake of peas in dirty tonnes Date Actual Daily plan Date Actual Daily plan Date Actual Daily plan 36 40 28/6 29/6 30/6 1/7 2/7 3/7 4/7 5/7 6/7 777 8/7 9/7 10/7 11/7 12/7 169 295 394 427 562 661 613 590 565 559 466 464 486 196 374 437 392 557 616 624 624 566 580 513 480 488 13/7 14/7 15/7 16/7 17/7 18/7 19/7 20/7 21/7 22/7 23/7 24/7 25/7 26/7 27/7 568 543 496 524 633 596 548 433 408 401 418 220 379 451 560 564 496 521 488 622 608 621 496 474 416 420 366 382 455 469 28/7 29/7 30/7 31/7 1/8 2/8 3/8 4/8 5/8 6/8 7/8 8/8 9/8 10/8 Total 609 460 496 438 558 600 626 527 428 273 148 122 46 17 18813 562 505 547 491 573 615 711 625 435 376 220 110 88 48 19791 load, and sample peas are extracted and taken directly into the quality room. Three samples are taken, from which the tenderness of the pea, percentage of unwanted material, and dirtiness is measured. Should any of the values not be within control standards, the load will not be accepted. The whole checking procedure takes between five and ten minutes. Once accepted, the lorries are weighed with the full load of peas and after having tipped the load into the receiving hoppers, the lorries are weighed again empty. The drivers are given receipts detailing the tonnes deliv- ered and quality. The whole weighing-tip-weighing procedure takes ten minutes on average, provided that there is a receiving hopper immediately available. Records are kept of the total daily deliveries from farmers, and of the expected tonnage (the daily plan'), based on the previous day's field inspections by the Sample Man, as shown in Table 28.2. The expression 'dirty tonnes' simply means that the peas are delivered as they are without being cleaned. They are cleaned when they come to the factory, and go into processing. The target for the supply from growers this year in dirty tonnes had been 18 660 tonnes, but the actual deliv- eries were slightly higher at 18 813 tonnes. In the control room John Lincoln often talked to the staff in the control room, the hub of the linkage between the harvest, transport and production processes. He was thinking back to some of the comments he had heard during the day. When John had come in to the control room, Tim Wallace, the shift manager, had been explaining their role to a visitor: 'You can see, from this position, how the whole factory is planned and run. Whatever is done here affects the whole process. From the tipping of the lorries of peas, to the feed- ing of the lines, blanchers and freezers.' Peas 275 Behind him was the babble of voices of the other people working in the room. One had just received a call from a farmer, apologising that they could not deliver as many peas as planned at their sceduled five minute 'slot' one hour later. One of the new summer planners had immediately changed the figure on the board, the main planning instrument, according to the new information. Tim had crossed out and changed the figure just written down, and had quietly explained to the visitor: "You have to keep an eye on them all the time! We have so many new employees during the summer. Our workforce increases from 200 in the winter to almost 400. You have to teach them everything, from the start. On his way back to his office, John had walked past the cleaning lines, one of which was standing idle, so he asked an operator what the problem was. 'Oh, it has just clogged again, but it will soon be back running! It was much worse yes- terday ... a load of peas was accidently tipped outside the hoppers, which prevented us from tipping there for a time while we cleared up. They had to stop one of the viners for an hour or so, I heard.' There are three shifts in the control room: one night shift from 23.007.00; two day shifts, from 7.00-15.00, and from 15.0023.00. There is a CB (citizens band) radio to communicate with the viners and lorries, and everything that has affected the schedule of deliveries is recorded in detail. The factory Once the lorries have been emptied into the hoppers, the peas are conveyed in seg- regated batches into one of three production lines in the factory. According to the control room manager, the maximum planned input is 12 tonnes/hour of dirty feed for Lines 1 and 3, and 10 tonnes/hour for Line 2. The peas go into bulk feeders and up on to the weighing belt, and then to the 'pod and stick machine' to take out stones, pods, small lumps of earth, and other unwanted materials. When processing peas, approximately 10 per cent of tonnage is removed in transforming dirty peas to clean, and around a further 10 per cent is lost when transforming clean to frozen. The segregation of batches is critical, to maintain traceability and ensure that dif- ferent grades are not inadvertently mixed. The peas then go into small hoppers known as 'scacos' which hold a small buffer of inventory to smooth out the flow, and then to collecting points, from there they are transported in water, pumped along pipes. These lead directly to the water or steam blanchers, where the peas are heated in approximately 90 seconds to 98 degrees Celsius. After the blanching, there is a cooling down process and quality check, where the content of starch can be sampled. The peas are then pumped in water to the freezer house, where there are three freezers, with capacities which are detailed in Table 28.3. The peas flow continu- ously into the freezers and are collected at the end into bulk pallet containers, each of about one tonne capacity. The output of frozen peas is weighed and labelled, allowing traceability of each harvested batch, before being transported into the cold 5 Part 4. Planning and control Table 28.3 Nominal capacity of the three freezers Freezer number Tonnes/hour 1 2 3 Total 10 7.5* 10 27.5 * No 2 revised from 10 to 7.5 because of age (19 years) store by fork-lift truck. Peas must exit the freezers at, or below, minus 18 degrees Celsius. Figure 28.2 illustrates the main process stages. Each freezer is made up of five separate sections, each with refrigeration coils (cold surfaces behind which refrigerant is passed). The outside of these tend to 'ice-up' fairly quickly, reducing their cooling efficiency, so each section is automatically defrosted while the peas continue to be frozen in the remaining sections. Depending on certain factors, such as temperature, the moisture of the inputs and the weather, the rate of icing-up increases, and overall effectiveness of the process declines, being detected by an upward trend in the output temperature of the peas. At this point, the input feed rate must be reduced, affecting the actual output capacity of the freezer, and slowing down the feed rate for the cleaning and blanching process because there is almost no in-process storage between blanching and freezing. For the same reason, any problems with the cleaning and blanching processes quickly deprive a freezer of its input, wasting valuable freezer capacity. Figure 28.2 Factory processes and layout Collecting and scacos Factory building 1 Cleaning and Hoppers Conveyors destoning Blanching Cooling and quality check Pump Bulk output Freezers Factory building 2 Manual quality control Peas 277 Quality and hygiene requirements Through the whole process there are stringent quality checks, and if batches of peas are not immediately accepted, they are quarantined and labelled accordingly. There are three standard places for quality checks: one in-process quality check; one check at the freezer output, and one when the peas are repackaged later for retail sale. Whenever capacity is a constraint, the bulk pallet containers of quarantined peas are taken into cold storage and dealt with later. Up to 30 per cent of the peas may be quarantined, but this does not seem to be a problem, as they can be dealt with later. The frozen peas can be fed through the automated 'Sortex' colour sorter, where any that are discoloured (and may therefore have a sour taste) or are other- wise bad are extracted. In n order to operate under hygienic conditions and to operate the freezers at as near to maximum capacity as possible, they are scheduled (see Table 28.4) to be reg- ularly defrosted, completely cleaned out and sterilised. It takes eight hours for each freezer to be defrosted. Visiting the inside of a working freezer, one can see why defrosting is so essential: they are very big, with a length of about 15 metres and a width of about six metres. Before entry, it is necessary to wear insulating clothes, since the air temperature is around minus 35 degrees, and a wind is blowing, making it quite a frightening and breathtaking experience! A series of conveyor belts go through the whole freezer, and cold air is blown up from underneath making the peas jump and circulate some centimetres above the conveyor while they freeze. Snow can build up on the floor to more than ten cen- timetres deep, and icicles hang from everywhere in the roof. The walls are covered with snow and ice. Table 28.4 Typical 'hygiene' cycle schedule Day Freezers defrosted 1 2 3 and 2 Nil 1 and 2 4 5 6 3 2 1 Breakdowns and mechanical downtime Problems in form of breakdowns are dealt with by the Process Manager, who has a team of full-time skilled employees, plus contractors if required. Unplanned en- gineering downtime can arise because of mechanical, electrical, refrigeration, or other technical problems. Time is planned for preventative maintenance, in order to keep the equipment in optimal condition to cope with the pressures of the har- vest. This planned downtime reduces operating utilisation on each of the cleaning/blanching lines to 95 per cent of operating time. Planned maintenance of the freezers is carried out during the hygiene downtime described above. 3 Part 4. Planning and control CASE 28 Peas Case date 1995 Stuart Chambers and Tammy Helander Introduction John Lincoln nodded goodbye to the guard and drove out of the gates of his large factory, situated in a fertile coastal region of eastern England. He drove home through a soft rolling landscape, surrounded by shimmering green fields towards a darkening early September sky, but the sight of this beautiful summer scene gave him little peace of mind. It just made him worry more about peas and pea fields. Peas that had to be harvested, transported to the factory, cleaned, processed, frozen, and packaged. And soon plans had to be completed for next year's pea crop, because as Factory Manager, he had to look ahead to ensure that all the production processes would be prepared to cope with the requirements of the increasingly demanding customers. This year had been difficult. The weather had been exceptionally good, which meant that the harvesting period had been much shorter than usual, putting pres- sure on the factory, which only had a limited daily processing capacity. The factory was designed to produce a range of frozen vegetables including carrots, cauliflowers, beans, peas, petit pois, broccoli, and sprouts. It belonged to a large specialist food group, and had an enviable reputation for its high quality standards. Despite John's many years of production management experience, the pea pro- cessing operation had always been his greatest headache during the summer season. The previous year had turned out to be an exceptionally long harvesting period of 65 days, which was relatively easy to cope with. However, this year's season, because of the fine weather, had shrunk to a more normal 44 days, which had meant an immense pressure in getting about the same tonnage of peas through the factory in the much shorter period. Peas always caused the worst problems, as they were by far the largest crop handled by the factory, and had to be processed in a very short time after being picked. John had discussed many times with the Crop Planning Manager, Dave Ronson, the possibility of extending the pea growing season to lessen the pressure on the factory but it was difficult to make any further changes. As Dave explained: 'Well, unfortunately you can't plan the weather! Certainly, we do influence when the peas should be ready for vining (picking) by using the best possible planning to ensure that the harvest is spread out over as long a time as possible. You know as well as I do, that the distribution of harvest times can be manipulated; for example, by using selected south and north facing fields, different varieties of seed, and planting at different altitudes above sea level. We have continuously worked to make this planning better, Peas 269 and to have better cooperation with the growers. We have managed to get them to agree on a target growing plan period of 44 days instead of 36, which is the normal con- tract period for growers supplying other factories. But there is a limit in how much we can extend the season - the peas will simply not grow over a longer period, and I believe we have reached the limit. The yields are also different, depending on the harvesting period. For the first and last quarter of the period the yield is only around 3.5 tonnes per hectare, whereas in the middle the yield is as much as six tonnes per hectare. The grow- ers are naturally more interested in having their main harvest in the middle, for obvious economic reasons.' It was only two weeks after the last of this year's harvest had gone through the factory, and the group's operations director had scheduled the following Wednesday to meet with John and the management team. They would go through this year's output figures compared to targets. Each year's targets were set on how many tonnes of frozen peas they would have to produce to satisfy anticipated customer demand. The company Although the frozen vegetable business had achieved only slow organic growth, it had continued to invest in improved processing facilities, and to develop better product quality through agricultural technology and practices, as well as by using leading freezing technology. In this way, the company ensured that the products were fresh and of high quality, and this was controlled by taking appropriate measurements on samples at every stage of processing from the field to the final packing in the factory. Most of the immediate customers were large and powerful retailers with very specific requirements for taste, colour, size, tenderness, etc. The number of factory employees varied between 400 and 200, depending whether it was the peak harvest season or not. Most of the important functions were all on- site, including production and marketing, but some additional cold storage and transportation resources were provided by contractors. The market for peas The total market for vining peas (the pea type that is best suited to quick freezing) in the UK is about 200 000 tonnes per annum and the growing area is around 40 000 hectares. The human consumption markets (there are some sorts of peas used for animal feed) are quite static, but remain important for vining pea growers, who have invested in expensive, specialised equipment for harvesting the crop. The typical annual pattern of demand in the UK for frozen peas is just the oppo- site of that of supply. Peas from growers all come in during three summer months with the harvesting lasting between 40 and 60 days, and with the main peak in July. In contrast, sales are at a minimum in the summer, because of the good avail- ability of fresh vegetables, but peak during the winter from October to May, as shown in Figure 28.1. The company's sales target throughput of frozen peas for this year had been 15 115 tonnes, measured in the frozen state. Actual output had been slightly higher at 15 396 tonnes as shown in Table 28.1, much to the satisfaction of the management team. 270 Part 4. Planning and control Figure 28.1 Market for peas in the UK (previous year) Total market demand Frozen peas (000s tonnes) 18 16 12 9 6 3 0 F M A M - J A s 0 0 0 Table 28.1 Current year pea output in frozen tonnes Date Tonnes Date Tonnes Date Tonnes 29 13/7 14/7 15/7 16/7 17/7 18/7 28/6 29/6 30/6 1/7 217 3/7 4/7 5/7 6/7 7/7 8/7 9/7 1007 11/7 12/7 134 241 320 349 454 543 500 476 462 461 376 379 401 19/7 20/7 21/7 22/7 23/7 24/7 25/7 26/7 27/7 467 449 411 463 524 492 452 358 337 336 335 179 305 363 452 28/7 29/7 30/7 31/7 1/8 2/8 3/8 4/8 5/8 6/8 7/8 8/8 9/8 10/8 TOTAL 489 370 404 350 450 488 514 435 351 226 120 102 36 13 15 396 Retail customers Most of the total market is held by the bigger retailers, including Asda, Safeway, KwikSave, Iceland, Somerfield, Tesco, and Sainsbury. For a producer to be approved by a large retailer, it is critical to offer the right price and the right quality. John's factory focused mainly on the needs of these very demanding UK retailers. Sales can be either in bulk form (which are subsequently prepared for retail sale by contract packers), or in branded or own-label retail packs within cardboard cases, according to requirements. Exports are only in this packed form and only account for a small proportion of sales. Prices depend on which quality the customers ask Peas 271 for, as the peas are graded in qualities ranging from AA to D, where AA is the top grade. The goal is to make as many AA graded peas as possible. The factory had built up an enviable reputation with the retailers for the quality of the product and ser- vices provided. Despite this, everyone was continually seeking ways of further increasing quality. For instance, it was known that the recently installed steam blancher should improve final pea quality. A blancher is basically the equipment where the peas get a rapid pre-cook, either in water or in steam, to stop enzymes action which breaks down natural sugars in the peas. This would give tangible benefits in terms of tex- ture and taste, which could then be marketed at premium prices. By improving the overall quality of output, the resulting improved profitability would make it poss- ible to reinvest in order to further improve the equipment, thereby achieving even higher levels of quality in the future. Marketing and competitors There were about six direct competitors that operated on a sufficiently large scale to supply the major retailers. One in particular was privately owned, and sometimes used aggressive pricing, apparently to gain market share. In contrast, John tried to maintain high utilisation of capacity in order not to increase unit fixed costs, but some competitors were known to hold considerable spare plant capacity which was only in full use during the peak harvest season, According to the Marketing Manager, Chris Johnson, the most important factor in the success of the business was its ability to enhance the customers' frozen vegetable business, and to initiate quality projects, in line with detailed knowledge of the retailers' requirements. They had the market understanding, and good development resources and skills to achieve this success. Unlike many competitors which offered a wider range of frozen foods including pizzas, pies, and gateaux, the account man- agers here were able to focus only on selling vegetables, which kept their knowledge and interest high Chris was very conscious of the necessity of close cooperation between the factory and Marketing, in order to sustain and improve success in terms of customers. He liked the fact that the marketing function was now located at the factory, creating an understanding and ambition for the site from the customers account managers. Chris was quite proud both of their external and internal relations: I think our customers like dealing with us, because we are usually able to provide them with exactly what they want. We specialise in vegetables and we always try to help them with all their special requirements, for example special pack sizes and graphics to assist in their promotions. We have good cooperation with the factory as well. We simply would not ask the factory to do something that it could not do. We talk every day to the planning people at the factory.' Factory processes and customer service Another important factor was the short line of communication along the supply chain, and the ability to adapt. The company had extremely good trade relations and supply partnerships, and the factory tried to always be very responsive. The target 272 Part 4. Planning and control service level of 98.5 per cent delivery dependability was usually met or exceeded. Marketing was constantly updating its demand forecasts, and checked these against the factory capabilities. They also gained from having big company back-up, as they at any time could call upon the technical or commercial help of the group. An important characteristic of the operation was that it had good control of the whole process, from the farms to the cold storage rooms. Some of the competitors had great difficulties in controlling their supply chains, and tended to depend more on the open market for the vegetables as it unfolded each season. In contrast, the close and detailed cooperation here between the marketing and factory operations, and between the suppliers and factory, impressed most customers. However, there were some unique difficulties in the planning of the pea business. The sowing/growing plan had to be set nearly one year ahead of the demand for peas in the following year. Therefore, the forecast from the marketing/sales depart- ment had to be made long before getting firm orders from any of the customers. The customers committed themselves firstly around May, by which time all the peas were planted and some of them were in flower, Conditions for pea growing Commercial pea crops are mainly grown in the east of England because of the par- ticular we needed for a quality . summ rainfall would make it messy and expensive to harvest and to clean, so reasonably dry weather is an advantage. In the eastern areas these conditions are met, as there is usually less than 75mm of rain in the whole of July and August. The economics of pea growing is affected by things like crop rotation, soil condi- tion, feed, weed control, machinery, as well as post-harvest handling. The crop has to be rotated, using a field only every fifth year or sometimes even only each sev- enth year before it is possible to grow peas or related crops again. The peas provide a valuable soil-improving crop, since they 'fix' nitrogen from the air into the soil. There are many types of peas, but vining peas are harvested mechanically for pro- cessing and quick freezing. Suppliers: the pea growers The farmers that supply the factory are members of trading groups, which mutually own equipment and hire personnel for the vining pea season. The factory closely cooperates with five of these farmer groups. In cooperation with the growers, a sowing plan and a harvesting plan are prepared each year, which details the number of hectares and tonnes to be harvested every day during the season. The sowing of peas usually starts in the last week of February Some of the farmer groups have exclusive contracts with the business, but there are also some who have contracts with other processors. The crops are normally sit- uated within a 60 kilometre radius of the factory, because the growers have to be able to deliver within a short elapsed time from beginning each harvest run. This is to ensure that the time from picking to blanching does not exceed 140 minutes, a demanding internal specification designed to produce the highest quality peas. Peas 273 The vining in the fields Before vining can begin, the 'sample man' visits the fields and measures the tender- ness of the peas, and when this reaches exactly the right level, it is time to begin harvesting the following day. At each farm, a foreman is responsible for the detailed control of the vining process, and maintains constant radio contact with the control room at the factory. He is in charge of the planning and ordering of lorries, and for the timing of the emptying of the peas from the vining machines, which is done during harvesting, without having to stop. The tractor and trailer simply drives alongside the vining machine, and the crop is discharged in one or two tonne batches into the trailer. These are then driven to lorries, and the peas are discharged into them up to the maximum required weight. The work shifts are different for each of the farmer groups, but in most cases the vining machines are used for around 19 hours a day, with five hours for cleaning and preventative maintenance. There is an average of three harvesting machines per farming group. Usually, two machines work all the time and the third is held in reserve, to be used if one suffered a breakdown or if the pea factory asks for more peas. The workers are employed on two shifts; a night shift from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., and a day shift from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., continuing seven days a week, every week until the pea season is over. This is demanding work, and sometimes stressful when vining on sloping fields. The huge machines, known affectionately as 'big drums' by the drivers, eat their way up and down the fields, irrespective of the weather. The only break in the humming driver's cab is the contact with the staff in the other viners and the tractor using the walkie-talkie radio. There is one full-time main- tenance man, as it is important to keep these 250 000 machines going, not least because of the potential costs of delays in terms of lost revenue and scrap peas, but also because of the importance of keeping a reliable supply for the factory, When the peas are being vined, the whole plants are cut and rolled over drums to separate the peas from the pods and stems. They then pass into a drum, where the peas roll down to the transporter belt, which takes them up to the hopper, where they can be seen from the driver's seat. The normal harvesting speed is around six tonnes/hour, but in ideal conditions can achieve around eight tonnes/hour. Transportation to and arrival at the factory control room The time from the beginning of harvesting to arriving at the factory should be below 90 minutes. This is vital in order to ensure a consistent high quality of the frozen peas, and so the farmers are careful to keep within the time, particularly as they are being paid on the quality of the peas they are delivering. The lorries are owned both by large haulage firms and by individual lorry owners who come back and operate during the pea season year after year. The capacity of the lorries ranges from four tonnes to eighteen tonnes, but they do not normally load more than about five tonnes per journey, as the lorries need to get quickly to the factory. They average around 45 km per hour on the journey along country roads and lanes. When the lorries arrive at the factory, they first stop at the control room for the quality check, to see if the load will be accepted. A collection tube is put into the 274 Part 4. Planning and control Table 28.2 Actual and planned intake of peas in dirty tonnes Date Actual Daily plan Date Actual Daily plan Date Actual Daily plan 36 40 28/6 29/6 30/6 1/7 2/7 3/7 4/7 5/7 6/7 777 8/7 9/7 10/7 11/7 12/7 169 295 394 427 562 661 613 590 565 559 466 464 486 196 374 437 392 557 616 624 624 566 580 513 480 488 13/7 14/7 15/7 16/7 17/7 18/7 19/7 20/7 21/7 22/7 23/7 24/7 25/7 26/7 27/7 568 543 496 524 633 596 548 433 408 401 418 220 379 451 560 564 496 521 488 622 608 621 496 474 416 420 366 382 455 469 28/7 29/7 30/7 31/7 1/8 2/8 3/8 4/8 5/8 6/8 7/8 8/8 9/8 10/8 Total 609 460 496 438 558 600 626 527 428 273 148 122 46 17 18813 562 505 547 491 573 615 711 625 435 376 220 110 88 48 19791 load, and sample peas are extracted and taken directly into the quality room. Three samples are taken, from which the tenderness of the pea, percentage of unwanted material, and dirtiness is measured. Should any of the values not be within control standards, the load will not be accepted. The whole checking procedure takes between five and ten minutes. Once accepted, the lorries are weighed with the full load of peas and after having tipped the load into the receiving hoppers, the lorries are weighed again empty. The drivers are given receipts detailing the tonnes deliv- ered and quality. The whole weighing-tip-weighing procedure takes ten minutes on average, provided that there is a receiving hopper immediately available. Records are kept of the total daily deliveries from farmers, and of the expected tonnage (the daily plan'), based on the previous day's field inspections by the Sample Man, as shown in Table 28.2. The expression 'dirty tonnes' simply means that the peas are delivered as they are without being cleaned. They are cleaned when they come to the factory, and go into processing. The target for the supply from growers this year in dirty tonnes had been 18 660 tonnes, but the actual deliv- eries were slightly higher at 18 813 tonnes. In the control room John Lincoln often talked to the staff in the control room, the hub of the linkage between the harvest, transport and production processes. He was thinking back to some of the comments he had heard during the day. When John had come in to the control room, Tim Wallace, the shift manager, had been explaining their role to a visitor: 'You can see, from this position, how the whole factory is planned and run. Whatever is done here affects the whole process. From the tipping of the lorries of peas, to the feed- ing of the lines, blanchers and freezers.' Peas 275 Behind him was the babble of voices of the other people working in the room. One had just received a call from a farmer, apologising that they could not deliver as many peas as planned at their sceduled five minute 'slot' one hour later. One of the new summer planners had immediately changed the figure on the board, the main planning instrument, according to the new information. Tim had crossed out and changed the figure just written down, and had quietly explained to the visitor: "You have to keep an eye on them all the time! We have so many new employees during the summer. Our workforce increases from 200 in the winter to almost 400. You have to teach them everything, from the start. On his way back to his office, John had walked past the cleaning lines, one of which was standing idle, so he asked an operator what the problem was. 'Oh, it has just clogged again, but it will soon be back running! It was much worse yes- terday ... a load of peas was accidently tipped outside the hoppers, which prevented us from tipping there for a time while we cleared up. They had to stop one of the viners for an hour or so, I heard.' There are three shifts in the control room: one night shift from 23.007.00; two day shifts, from 7.00-15.00, and from 15.0023.00. There is a CB (citizens band) radio to communicate with the viners and lorries, and everything that has affected the schedule of deliveries is recorded in detail. The factory Once the lorries have been emptied into the hoppers, the peas are conveyed in seg- regated batches into one of three production lines in the factory. According to the control room manager, the maximum planned input is 12 tonnes/hour of dirty feed for Lines 1 and 3, and 10 tonnes/hour for Line 2. The peas go into bulk feeders and up on to the weighing belt, and then to the 'pod and stick machine' to take out stones, pods, small lumps of earth, and other unwanted materials. When processing peas, approximately 10 per cent of tonnage is removed in transforming dirty peas to clean, and around a further 10 per cent is lost when transforming clean to frozen. The segregation of batches is critical, to maintain traceability and ensure that dif- ferent grades are not inadvertently mixed. The peas then go into small hoppers known as 'scacos' which hold a small buffer of inventory to smooth out the flow, and then to collecting points, from there they are transported in water, pumped along pipes. These lead directly to the water or steam blanchers, where the peas are heated in approximately 90 seconds to 98 degrees Celsius. After the blanching, there is a cooling down process and quality check, where the content of starch can be sampled. The peas are then pumped in water to the freezer house, where there are three freezers, with capacities which are detailed in Table 28.3. The peas flow continu- ously into the freezers and are collected at the end into bulk pallet containers, each of about one tonne capacity. The output of frozen peas is weighed and labelled, allowing traceability of each harvested batch, before being transported into the cold 5 Part 4. Planning and control Table 28.3 Nominal capacity of the three freezers Freezer number Tonnes/hour 1 2 3 Total 10 7.5* 10 27.5 * No 2 revised from 10 to 7.5 because of age (19 years) store by fork-lift truck. Peas must exit the freezers at, or below, minus 18 degrees Celsius. Figure 28.2 illustrates the main process stages. Each freezer is made up of five separate sections, each with refrigeration coils (cold surfaces behind which refrigerant is passed). The outside of these tend to 'ice-up' fairly quickly, reducing their cooling efficiency, so each section is automatically defrosted while the peas continue to be frozen in the remaining sections. Depending on certain factors, such as temperature, the moisture of the inputs and the weather, the rate of icing-up increases, and overall effectiveness of the process declines, being detected by an upward trend in the output temperature of the peas. At this point, the input feed rate must be reduced, affecting the actual output capacity of the freezer, and slowing down the feed rate for the cleaning and blanching process because there is almost no in-process storage between blanching and freezing. For the same reason, any problems with the cleaning and blanching processes quickly deprive a freezer of its input, wasting valuable freezer capacity. Figure 28.2 Factory processes and layout Collecting and scacos Factory building 1 Cleaning and Hoppers Conveyors destoning Blanching Cooling and quality check Pump Bulk output Freezers Factory building 2 Manual quality control Peas 277 Quality and hygiene requirements Through the whole process there are stringent quality checks, and if batches of peas are not immediately accepted, they are quarantined and labelled accordingly. There are three standard places for quality checks: one in-process quality check; one check at the freezer output, and one when the peas are repackaged later for retail sale. Whenever capacity is a constraint, the bulk pallet containers of quarantined peas are taken into cold storage and dealt with later. Up to 30 per cent of the peas may be quarantined, but this does not seem to be a problem, as they can be dealt with later. The frozen peas can be fed through the automated 'Sortex' colour sorter, where any that are discoloured (and may therefore have a sour taste) or are other- wise bad are extracted. In n order to operate under hygienic conditions and to operate the freezers at as near to maximum capacity as possible, they are scheduled (see Table 28.4) to be reg- ularly defrosted, completely cleaned out and sterilised. It takes eight hours for each freezer to be defrosted. Visiting the inside of a working freezer, one can see why defrosting is so essential: they are very big, with a length of about 15 metres and a width of about six metres. Before entry, it is necessary to wear insulating clothes, since the air temperature is around minus 35 degrees, and a wind is blowing, making it quite a frightening and breathtaking experience! A series of conveyor belts go through the whole freezer, and cold air is blown up from underneath making the peas jump and circulate some centimetres above the conveyor while they freeze. Snow can build up on the floor to more than ten cen- timetres deep, and icicles hang from everywhere in the roof. The walls are covered with snow and ice. Table 28.4 Typical 'hygiene' cycle schedule Day Freezers defrosted 1 2 3 and 2 Nil 1 and 2 4 5 6 3 2 1 Breakdowns and mechanical downtime Problems in form of breakdowns are dealt with by the Process Manager, who has a team of full-time skilled employees, plus contractors if required. Unplanned en- gineering downtime can arise because of mechanical, electrical, refrigeration, or other technical problems. Time is planned for preventative maintenance, in order to keep the equipment in optimal condition to cope with the pressures of the har- vest. This planned downtime reduces operating utilisation on each of the cleaning/blanching lines to 95 per cent of operating time. Planned maintenance of the freezers is carried out during the hygiene downtime described above. 3 Part 4. Planning and control

prepare graphs showing : (a) the daily output compared to design and effective capacity (b) cumulative output compared to cumulative design and effective capacity what do these tell us about the operation ?

prepare graphs showing : (a) the daily output compared to design and effective capacity (b) cumulative output compared to cumulative design and effective capacity what do these tell us about the operation ?