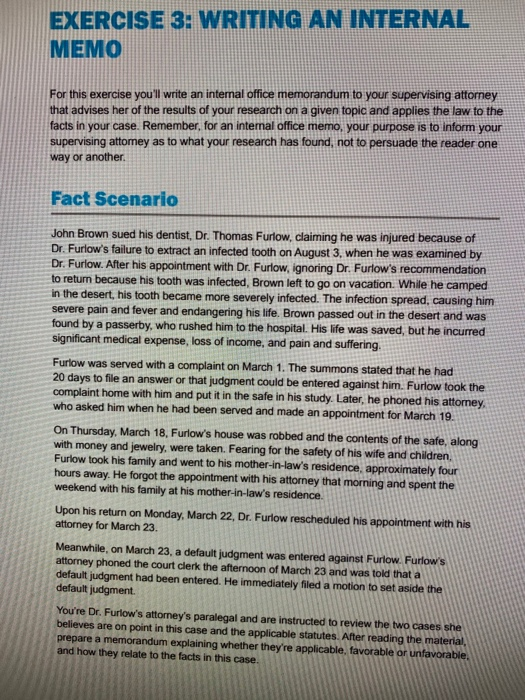

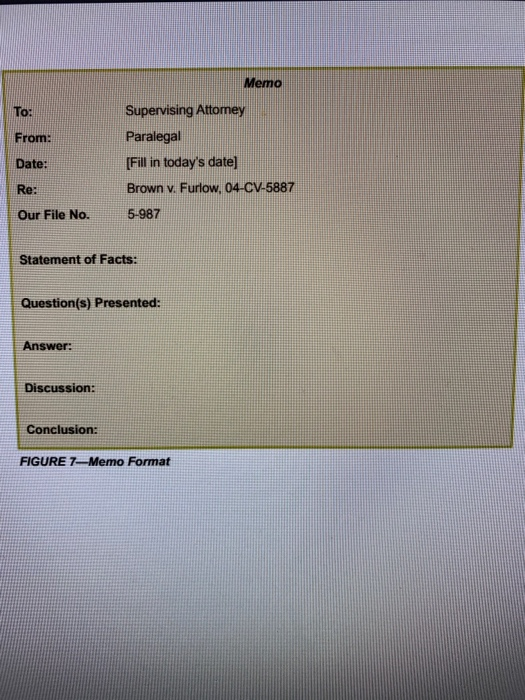

Question: The Question is the first image where it says For this Exercise. The last picture gives the Memo Template. EXERCISE 3. WRITING AN INTERNAL MEMO

The Question is the first image where it says For this Exercise. The last picture gives the Memo Template.

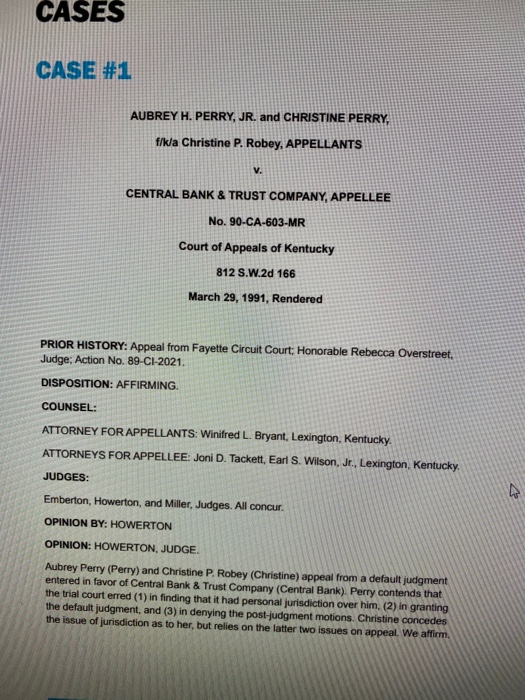

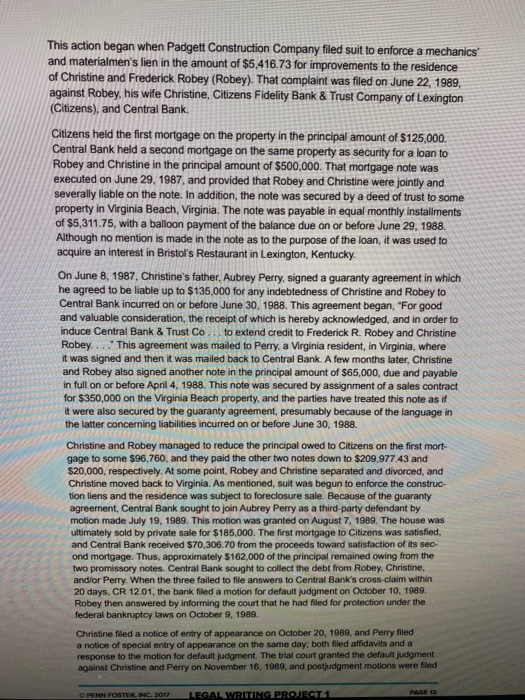

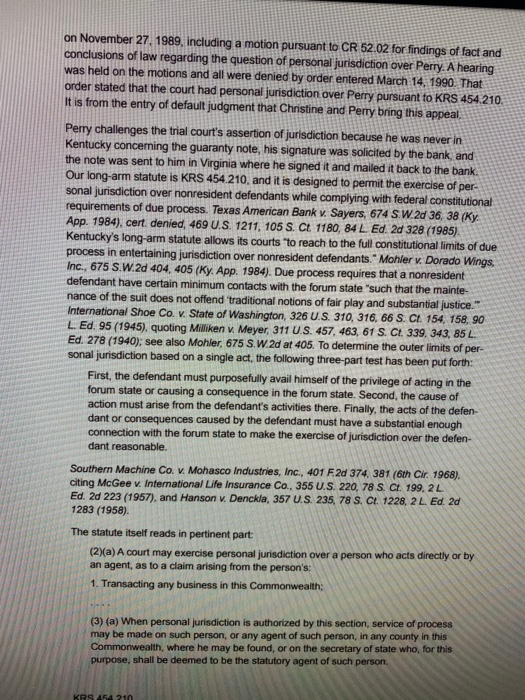

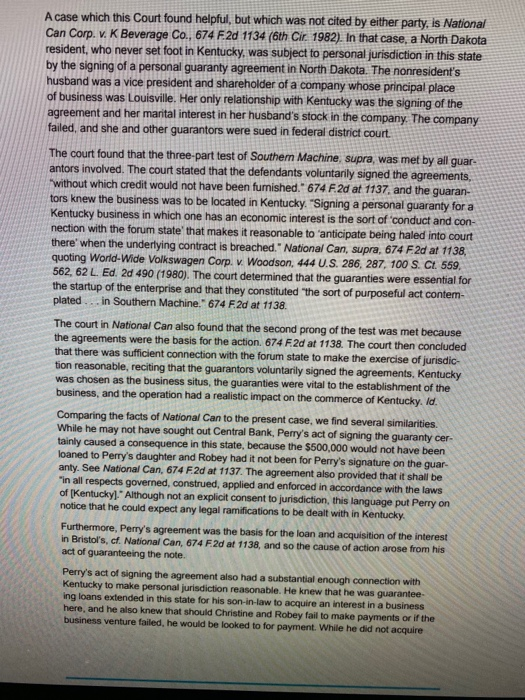

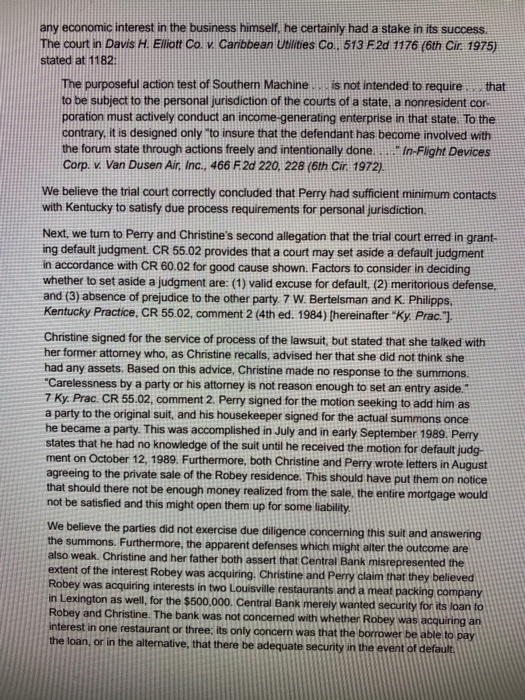

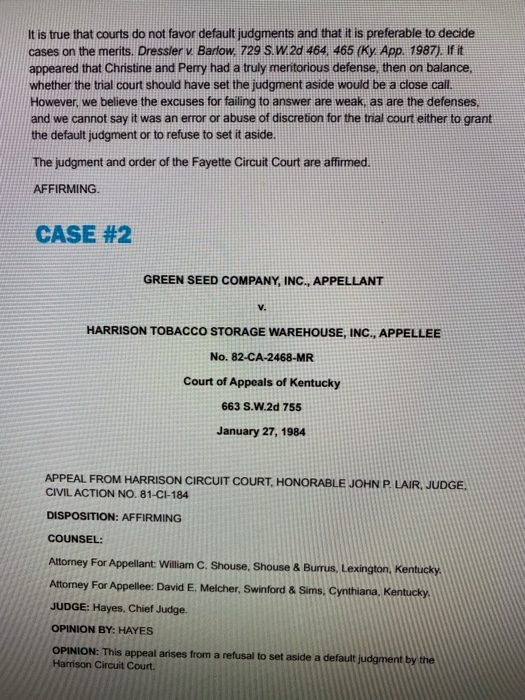

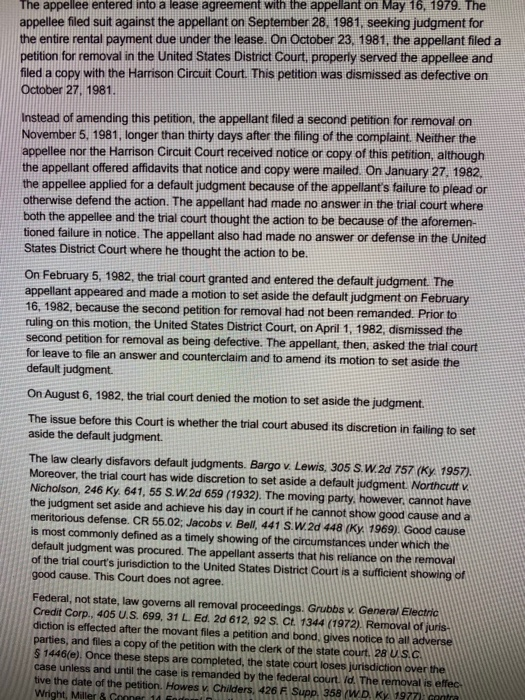

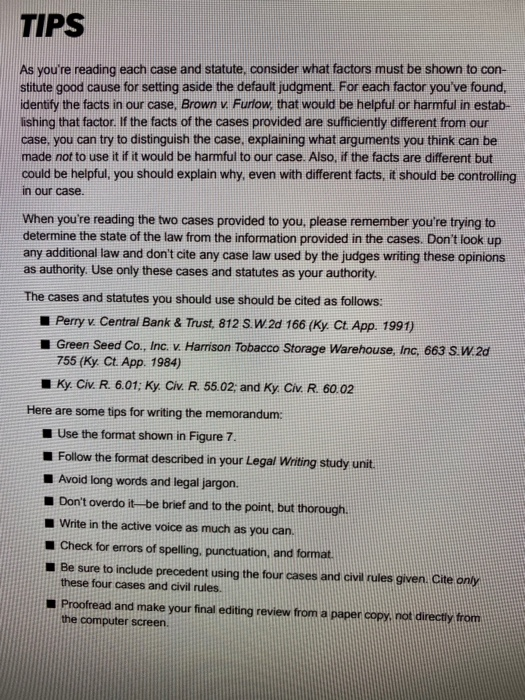

EXERCISE 3. WRITING AN INTERNAL MEMO For this exercise you'll write an internal office memorandum to your supervising attorney that advises her of the results of your research on a given topic and applies the law to the facts in your case. Remember, for an internal office memo, your purpose is to inform your supervising attorney as to what your research has found, not to persuade the reader one way or another Fact Scenario John Brown sued his dentist, Dr. Thomas Furlow, claiming he was injured because of Dr. Furlow's failure to extract an infected tooth on August 3, when he was examined by Dr. Furlow. After his appointment with Dr. Furlow, ignoring Dr. Furlow's recommendation to return because his tooth was infected, Brown left to go on vacation. While he camped in the desert, his tooth became more severely infected. The infection spread, causing him severe pain and fever and endangering his life. Brown passed out in the desert and was found by a passerby, who rushed him to the hospital. His life was saved, but he incurred significant medical expense, loss of income, and pain and suffering. Furlow was served with a complaint on March 1. The summons stated that he had 20 days to file an answer or that judgment could be entered against him. Furlow took the complaint home with him and put it in the safe in his study. Later, he phoned his attorney, who asked him when he had been served and made an appointment for March 19. On Thursday, March 18, Furlow's house was robbed and the contents of the safe, along with money and jewelry, were taken. Fearing for the safety of his wife and children, Furlow took his family and went to his mother-in-law's residence, approximately four hours away. He forgot the appointment with his attorney that morning and spent the weekend with his family at his mother-in-law's residence Upon his return on Monday, March 22, Dr. Furlow rescheduled his appointment with his attorney for March 23. Meanwhile, on March 23, a default judgment was entered against Furlow. Furlow's attorney phoned the court clerk the afternoon of March 23 and was told that a default judgment had been entered. He immediately filed a motion to set aside the default judgment. You're Dr. Furlow's attorney's paralegal and are instructed to review the two cases she believes are on point in this case and the applicable statutes. After reading the material, prepare a memorandum explaining whether they're applicable, favorable or unfavorable, and how they relate to the facts in this case. CASES CASE #1 AUBREY H. PERRY, JR. and CHRISTINE PERRY, f/k/a Christine P. Robey, APPELLANTS V. CENTRAL BANK & TRUST COMPANY, APPELLEE No. 90-CA-603-MR Court of Appeals of Kentucky 812 S.W.2d 166 March 29, 1991, Rendered PRIOR HISTORY: Appeal from Fayette Circuit Court: Honorable Rebecca Overstreet. Judge: Action No. 89-CI-2021. DISPOSITION: AFFIRMING. COUNSEL: ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANTS: Winifred L. Bryant, Lexington, Kentucky ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE: Joni D. Tackett, Earl S. Wilson, Jr., Lexington, Kentucky. JUDGES: Emberton, Howerton, and Miller, Judges. All concur. OPINION BY: HOWERTON OPINION: HOWERTON, JUDGE. Aubrey Perry (Perry) and Christine P. Robey (Christine) appeal from a default judgment entered in favor of Central Bank & Trust Company (Central Bank). Perry contends that the trial court erred (1) in finding that it had personal jurisdiction over him, (2) in granting the default judgment, and (3) in denying the post-judgment motions. Christine concedes the issue of jurisdiction as to her, but relies on the latter two issues on appeal. We affirm, This action began when Padgett Construction Company filed suit to enforce a mechanics' and materialmen's lien in the amount of $5,416.73 for improvements to the residence of Christine and Frederick Robey (Robey). That complaint was filed on June 22, 1989, against Robey, his wife Christine, Citizens Fidelity Bank & Trust Company of Lexington (Citizens), and Central Bank Citizens held the first mortgage on the property in the principal amount of $125,000. Central Bank held a second mortgage on the same property as security for a loan to Robey and Christine in the principal amount of $500,000. That mortgage note was executed on June 29, 1987, and provided that Robey and Christine were jointly and severally liable on the note. In addition, the note was secured by a deed of trust to some property in Virginia Beach, Virginia. The note was payable in equal monthly installments of $5,311.75, with a balloon payment of the balance due on or before June 29, 1988. Although no mention is made in the note as to the purpose of the loan, it was used to acquire an interest in Bristol's Restaurant in Lexington, Kentucky. On June 8, 1987, Christine's father, Aubrey Perry, signed a guaranty agreement in which he agreed to be liable up to $135,000 for any indebtedness of Christine and Robey to Central Bank incurred on or before June 30, 1988. This agreement began, "For good and valuable consideration, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, and in order to induce Central Bank & Trust Co to extend credit to Frederick R. Robey and Christine Robey.... This agreement was mailed to Perry, a Virginia resident, in Virginia, where it was signed and then it was mailed back to Central Bank. A few months later, Christine and Robey also signed another note in the principal amount of $65,000, due and payable in full on or before April 4, 1988. This note was secured by assignment of a sales contract for $350,000 on the Virginia Beach property, and the parties have treated this note as if it were also secured by the guaranty agreement, presumably because of the language in the latter concerning liabilities incurred on or before June 30, 1988. Christine and Robey managed to reduce the principal owed to Citizens on the first mort- gage to some $96,760, and they paid the other two notes down to $209,977.43 and $20,000, respectively. At some point, Robey and Christine separated and divorced, and Christine moved back to Virginia. As mentioned, suit was begun to enforce the construc- tion liens and the residence was subject to foreclosure sale. Because of the guaranty agreement, Central Bank sought to join Aubrey Perry as a third-party defendant by motion made July 19, 1989. This motion was granted on August 7, 1989. The house was ultimately sold by private sale for $185,000. The first mortgage to Citizens was satisfied, and Central Bank received $70,306.70 from the proceeds toward satisfaction of its sec- ond mortgage. Thus, approximately $162,000 of the principal remained owing from the two promissory notes. Central Bank sought to collect the debt from Robey, Christine, and/or Perry. When the three failed to file answers to Central Bank's cross-claim within 20 days. CR 12.01, the bank filed a motion for default judgment on October 10, 1989. Robey then answered by informing the court that he had filed for protection under the federal bankruptcy laws on October 9, 1989. Christine filed a notice of entry of appearance on October 20, 1980, and Perry filed a notice of special entry of appearance on the same day, both filed affidavits and a response to the motion for default judgment. The trial court granted the default judgment against Christine and Perry on November 16, 1989, and postjudgment motions were filed PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 LEGAL WRITING PROJECT 1 PAGE 2 on November 27, 1989, including a motion pursuant to CR 52.02 for findings of fact and conclusions of law regarding the question of personal jurisdiction over Perry. A hearing was held on the motions and all were denied by order entered March 14, 1990. That order stated that the court had personal jurisdiction over Perry pursuant to KRS 454.210. It is from the entry of default judgment that Christine and Perry bring this appeal Perry challenges the trial court's assertion of jurisdiction because he was never in Kentucky concerning the guaranty note, his signature was solicited by the bank, and the note was sent to him in Virginia where he signed it and mailed it back to the bank. Our long-arm statute is KRS 454.210, and it is designed to permit the exercise of per- sonal jurisdiction over nonresident defendants while complying with federal constitutional requirements of due process. Texas American Bank v. Sayers, 674 S. W. 2d 36, 38 (Ky. App. 1984), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1211, 105 S. Ct 1180, 84 L. Ed.2d 328 (1985). Kentucky's long-arm statute allows its courts to reach to the full constitutional limits of due process in entertaining jurisdiction over nonresident defendants. Mohler v. Dorado Wings Inc., 675 S.W.2d 404 405 (Ky. App. 1984). Due process requires that a nonresident defendant have certain minimum contacts with the forum state "such that the mainte- nance of the suit does not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice." International Shoe Co. v. State of Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316,66 S. Ct. 154, 158, 90 L. Ed. 95 (1945), quoting Milliken v. Meyer, 311 U.S. 457, 463, 61 S. Ct. 339, 343, 85 L Ed. 278 (1940): see also Mohler, 675 S.W.2d at 405. To determine the outer limits of per- sonal jurisdiction based on a single act, the following three-part test has been put forth: First, the defendant must purposefully avail himself of the privilege of acting in the forum state or causing a consequence in the forum state. Second, the cause of action must arise from the defendant's activities there. Finally, the acts of the defen- dant or consequences caused by the defendant must have a substantial enough connection with the forum state to make the exercise of jurisdiction over the defen- dant reasonable. Southern Machine Co. v. Mohasco Industries, Inc., 401 F 2d 374 381 (6th Cir. 1968). citing McGee v. International Life Insurance Co., 355 U.S. 220,78 S. Ct. 199, 2L Ed.2d 223 (1957), and Hanson v Denckla, 357 U.S. 235, 78 S. Ct. 1228, 22. Ed. 2d 1283 (1958). The statute itself reads in pertinent part: (2)(a) A court may exercise personal jurisdiction over a person who acts directly or by an agent, as to a claim arising from the person's: 1. Transacting any business in this Commonwealth: (3) (a) When personal jurisdiction is authorized by this section, service of process may be made on such person, or any agent of such person, in any county in this Commonwealth, where he may be found, or on the secretary of state who, for this purpose, shall be deemed to be the statutory agent of such person KRS 454 210 A case which this Court found helpful, but which was not cited by either party is National Can Corp. v. K Beverage Co., 674 F.2d 1134 (6th Cir. 1982). In that case, a North Dakota resident, who never set foot in Kentucky, was subject to personal jurisdiction in this state by the signing of a personal guaranty agreement in North Dakota. The nonresident's husband was a vice president and shareholder of a company whose principal place of business was Louisville. Her only relationship with Kentucky was the signing of the agreement and her marital interest in her husband's stock in the company. The company failed, and she and other guarantors were sued in federal district court. The court found that the three-part test of Southern Machine, supra, was met by all guar- antors involved. The court stated that the defendants voluntarily signed the agreements, without which credit would not have been furnished.- 674 F.2d at 1137, and the guaran- tors knew the business was to be located in Kentucky. "Signing a personal guaranty for a Kentucky business in which one has an economic interest is the sort of conduct and con- nection with the forum state that makes it reasonable to anticipate being haled into court there when the underlying contract is breached." National Can, supra, 674 F2d at 1138, quoting World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286, 287, 100 S. Ct. 569. 562, 62 L. Ed. 2d 490 (1980). The court determined that the guaranties were essential for the startup of the enterprise and that they constituted "the sort of purposeful act contem- plated in Southern Machine." 674 F.2d at 1138 The court in National Can also found that the second prong of the test was met because the agreements were the basis for the action. 674 F.2d at 1138. The court then concluded that there was sufficient connection with the forum state to make the exercise of jurisdic- tion reasonable, reciting that the guarantors voluntarily signed the agreements, Kentucky was chosen as the business situs, the guaranties were vital to the establishment of the business, and the operation had a realistic impact on the commerce of Kentucky. Id. Comparing the facts of National Can to the present case, we find several similarities. While he may not have sought out Central Bank, Perry's act of signing the guaranty cer- tainly caused a consequence in this state, because the $500,000 would not have been loaned to Perry's daughter and Robey had it not been for Perry's signature on the guar- anty. See National Can, 674 F2d at 1137. The agreement also provided that it shall be "in all respects governed, construed, applied and enforced in accordance with the laws of (Kentuckyl. Although not an explicit consent to jurisdiction, this language put Perry on notice that he could expect any legal ramifications to be dealt with in Kentucky Furthermore, Perry's agreement was the basis for the loan and acquisition of the interest in Bristol's, cf. National Can, 674 F.2d at 1138, and so the cause of action arose from his act of guaranteeing the note. Perry's act of signing the agreement also had a substantial enough connection with Kentucky to make personal jurisdiction reasonable. He knew that he was guarantee ing loans extended in this state for his son-in-law to acquire an interest in a business here, and he also knew that should Christine and Robey fail to make payments or if the business venture failed, he would be looked to for payment. While he did not acquire any economic interest in the business himself, he certainly had a stake in its success. The court in Davis H. Elliott Co. v. Caribbean Utilities Co., 513 E2d 1176 (6th Cir. 1975) stated at 1182: The purposeful action test of Southern Machine. is not intended to require that to be subject to the personal jurisdiction of the courts of a state, a nonresident cor- poration must actively conduct an income generating enterprise in that state. To the contrary, it is designed only to insure that the defendant has become involved with the forum state through actions freely and intentionally done. in-Flight Devices Corp. v. Van Dusen Air, Inc., 466 F 20 220, 228 (6th Cir. 1972), We believe the trial court correctly concluded that Perry had sufficient minimum contacts with Kentucky to satisfy due process requirements for personal jurisdiction. Next, we turn to Perry and Christine's second allegation that the trial court erred in grant- ing default judgment. CR 55.02 provides that a court may set aside a default judgment in accordance with CR 60.02 for good cause shown. Factors to consider in deciding whether to set aside a judgment are: (1) valid excuse for default, (2) meritorious defense, and (3) absence of prejudice to the other party. 7 W. Bertelsman and K. Philipps. Kentucky Practice, CR 55.02, comment 2 (4th ed. 1984) (hereinafter "Ky. Prac."). Christine signed for the service of process of the lawsuit, but stated that she talked with her former attomey who, as Christine recalls, advised her that she did not think she had any assets. Based on this advice, Christine made no response to the summons. "Carelessness by a party or his attorney is not reason enough to set an entry aside." 7 Ky. Prac. CR 55.02, comment 2. Perry signed for the motion seeking to add him as a party to the original suit, and his housekeeper signed for the actual summons once he became a party. This was accomplished in July and in early September 1989. Perry states that he had no knowledge of the suit until he received the motion for default judg- ment on October 12, 1989. Furthermore, both Christine and Perry wrote letters in August agreeing to the private sale of the Robey residence. This should have put them on notice that should there not be enough money realized from the sale, the entire mortgage would not be satisfied and this might open them up for some liability. We believe the parties did not exercise due diligence concerning this suit and answering the summons. Furthermore, the apparent defenses which might alter the outcome are also weak. Christine and her father both assert that Central Bank misrepresented the extent of the interest Robey was acquiring. Christine and Perry claim that they believed Robey was acquiring interests in two Louisville restaurants and a meat packing company in Lexington as well, for the $500,000. Central Bank merely wanted security for its loan to Robey and Christine. The bank was not concerned with whether Robey was acquiring an interest in one restaurant or three: its only concern was that the borrower be able to pay the loan, or in the alternative, that there be adequate security in the event of default. It is true that courts do not favor default judgments and that it is preferable to decide cases on the merits. Dressler v Barlow, 729 S.W.2d 464, 465 (Ky. App. 1987). If it appeared that Christine and Perry had a truly mentorious defense, then on balance, whether the trial court should have set the judgment aside would be a close call. However, we believe the excuses for failing to answer are weak, as are the defenses. and we cannot say it was an error or abuse of discretion for the trial court either to grant the default judgment or to refuse to set it aside. The judgment and order of the Fayette Circuit Court are affirmed. AFFIRMING CASE #2 GREEN SEED COMPANY, INC., APPELLANT V. HARRISON TOBACCO STORAGE WAREHOUSE, INC., APPELLEE No. 82-CA-2468-MR Court of Appeals of Kentucky 663 S.W.2d 755 January 27, 1984 APPEAL FROM HARRISON CIRCUIT COURT, HONORABLE JOHN P. LAIR, JUDGE. CIVIL ACTION NO. 81-Cl-184 DISPOSITION: AFFIRMING COUNSEL: Attorney For Appellant: William C. Shouse, Shouse & Burrus, Lexington, Kentucky Attorney For Appellee: David E. Melcher, Swinford & Sims, Cynthiana, Kentucky. JUDGE: Hayes, Chief Judge. OPINION BY: HAYES OPINION: This appeal arises from a refusal to set aside a default judgment by the Harrison Circuit Court. The appellee entered into a lease agreement with the appellant on May 16, 1979. The appellee filed suit against the appellant on September 28, 1981. seeking judgment for the entire rental payment due under the lease. On October 23. 1981, the appellant filed a petition for removal in the United States District Court, properly served the appellee and filed a copy with the Harrison Circuit Court. This petition was dismissed as defective on October 27, 1981. Instead of amending this petition, the appellant filed a second petition for removal on November 5, 1981, longer than thirty days after the filing of the complaint. Neither the appellee nor the Harrison Circuit Court received notice or copy of this petition, although the appellant offered affidavits that notice and copy were mailed. On January 27. 1982, the appellee applied for a default judgment because of the appellant's failure to plead or otherwise defend the action. The appellant had made no answer in the trial court where both the appellee and the trial court thought the action to be because of the aforemen- tioned failure in notice. The appellant also had made no answer or defense in the United States District Court where he thought the action to be. On February 5, 1982, the trial court granted and entered the default judgment. The appellant appeared and made a motion to set aside the default judgment on February 16, 1982, because the second petition for removal had not been remanded. Prior to ruling on this motion, the United States District Court, on April 1, 1982, dismissed the second petition for removal as being defective. The appellant, then asked the trial court for leave to file an answer and counterclaim and to amend its motion to set aside the default judgment. On August 6, 1982, the trial court denied the motion to set aside the judgment. The issue before this Court is whether the trial court abused its discretion in failing to set aside the default judgment. The law clearly disfavors default judgments. Bargo v. Lewis, 305 S.W.2d 757 (Ky 1957). Moreover, the trial court has wide discretion to set aside a default judgment. Northcutt v. Nicholson, 246 Ky. 641, 55 S.W.2d 659 (1932). The moving party, however, cannot have the judgment set aside and achieve his day in court if he cannot show good cause and a meritorious defense. CR 55.02. Jacobs v. Bell, 441 S.W.2d 448 (Ky, 1969). Good cause is most commonly defined as a timely showing of the circumstances under which the default judgment was procured. The appellant asserts that his reliance on the removal of the trial court's jurisdiction to the United States District Court is a sufficient showing of good cause. This Court does not agree. Federal, not state, law governs all removal proceedings. Grubbs v. General Electric Credit Corp., 405 U.S. 699, 31 L. Ed.2d 612, 92 S. Ct. 1344 (1972). Removal of juris diction is effected after the movant files a petition and bond, gives notice to all adverse parties, and files a copy of the petition with the clerk of the state court. 28 U.S.C. $ 1446(e). Once these steps are completed, the state court loses jurisdiction over the case unless and until the case is remanded by the federal court. Id. The removal is effec tive the date of the petition. Howes v. Childers, 426 F Supp. 358 (WD. Ky 1977 Wright, Miller & court retains its jurisdiction until it is notified of the removal petition, this procedure allows an interim period between the filing of the petition and the notice to the parties and the state court where the federal and state courts both have jurisdiction. Berberian v. Gibney, 514 F.2d 790 (1st Cir. 1975). Howes, supra. Dual jurisdiction remained in the instant case at least until February 16, 1982, when the appellant's motion to set aside the default judgment first notified the appellee and the trial court of the second petition for removal. See Medrano v. State of Texas, 580 F.2d 803 (5th Cir. 1978). Where no notice, actual or constructive, is given to the state court, the trial court's actions are not void. ld. Obviously. conflicting actions can occur. Most courts find concurrent jurisdiction means nothing more than that once the state court is notified of the removal, federal jurisdiction predominates in any conflicting actions during this interim period. 1A Moore's Federal Practice 0.168 [-3-8) (1983). Howes, supra; contra; Wright 3737. In effect, then, the federal court can overturn any default judgment that had been granted during the period of dual jurisdiction. Id. Where, as in the case at bar, the federal court dismisses the petition, the removing party's only recourse is a motion to set aside the judgment, and reliance on his petition for removal as good cause may fail. When the removing party fails to answer in compliance with either CR 12.01 or Fed. R. Civ. P. 81, the trial court does not abuse its discretion in finding such reliance inadequate as good cause. CR 12.01 requires a defendant to serve his answer within twenty (20) days after service of the summons upon him. The appellant waited almost seven (7) months before he served the appellee with his answer. The default judgment was not granted until over three (3) months had elapsed after the time the appellant was required to tender his answer. The appellant's failure to file a timely answer is sufficient basis for a default judg- ment, and the appellant is not entitled to have the judgment set aside unless he can show reasonable excuse for the delay in answering and establish that he is not guilty of unrea- sonable delay. CR 55.01; Terrafirma, Inc. v. Krogdahl, 380 S.W.2d 86 (ky. 1964). The appellant's assertion that he believed the case had been removed is an unreason- able excuse when he has not complied with Fed. R. Civ. P. 81. This rule attempts to resolve the potential conflicts between the thirty (30) days allowed for removal under 28 U.S.C.S 1446, the twenty days allowed for an answer under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12, and the various times allowed for answers under state rules by providing. In a removed action in which the defendant has not answered, he shall answer or present the other defenses or objections available to him under these rules within 20 days after the receipt through service or otherwise of a copy of the initial plead- ing setting forth the claim for relief upon which the action or proceeding is based, or within 20 days after service of summons upon such initial pleading, then filed, or within 5 days after the filing of the petition for removal, whichever period is longer Fed. R. Civ. P. 81(c). The removing party, then, can wait until the longer of twenty (20) days after service or summons or five (5) days after the removal petition to answer the complaint and need not comply with state rules. The party, however, must answer. The appellant's failure to answer pursuant to this rule belies his reliance on the removal pro- ceedings and precludes his using this reliance as an excuse for delay. The appellant's reply brief suggests that good cause is further established because notice of the February 5. 1982 hearing was required by CR 55.01 and he received no notice. The record presents conflicting evidence as to whether the appellant received notice of the hearing. CR 55.01, however, requires noti only when the party has made an appearance before the court. Pound Mill Coal Co. v. Pennington, 309 S.W.2d 772 (Ky. 1958). While appellant argues the filing of the first petition for removal is an appearance, he has not appeared. The general rule of law holds that in the federal or state courts a petition for the removal of a cause to a federal court and the proceedings thereon do not constitute an appearance which waives jurisdictional objections or prevents defendant from being in default for want of appearance." 6 CJ.S. Appearances $ 32 (1975). The word "appeared in CR 55.01 means the defendant has so participated in the action as to indicate an intention to defend. Smith v. Gadd, 280 S.W.2d 495 (Ky. 1955). The appellant's failure to answer in any court for seven months contradicts any intention to defend and makes unnecessary the resolution of whether the appellant received notice. The trial court did not abuse its discretion in finding the appellant failed to show good cause. His failure to show good cause obviates any need for this court to determine whether the appellant presented a meritorious defense. The judgment is affirmed. ALL CONCUR. STATUTES Kentucky Civil Rule 6.01. Computation In computing any period of time prescribed or allowed by these rules, by order of court or by any applicable statute, the day of the act, event or default after which the designated period of time begins to run is not to be included. The last day of the period so computed is to be included, unless it is a Saturday, a Sunday or a legal holiday, in which event the period runs until the end of the next day which is not a Saturday, a Sunday or a legal holiday. When the period of time prescribed or allowed is less than seven days, intermediate Saturdays, Sundays and legal holidays shall be excluded in the computation. Kentucky Civil Rule 55.02. Setting Aside Default For good cause shown the court may set aside a judgment by default in accordance with Rule 60.02. Kentucky Civil Rule 60.02. Mistake; inadvertence; excusable neglect; newly discov. ered evidence; fraud; etc. On motion a court may, upon such terms as are just, relieve a party or his legal rep- resentative from its final judgment, order, or proceeding upon the following grounds: (a) mistake, inadvertence, surprise or excusable neglect; (b) newly discovered evi- dence which by due diligence could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial under Rule 59.02: (c) perjury or falsified evidence; (d) fraud affecting the proceedings, other than perjury or falsified evidence; (e) the judgment is vold, or has been satisfied, released, or discharged, or a prior judgment upon which it is based has been reversed or otherwise vacated, or it is no longer equitable that the judg- ment should have prospective application; or (1) any other reason of an extraordinary nature justifying relief. The motion shall be made within a reasonable time, and on grounds (a), (b), and (c) not more than one year after the judgment, order, or pro- ceeding was entered or taken. A motion under this rule does not affect the finality of a judgment or suspend its operation. TIPS As you're reading each case and statute, consider what factors must be shown to con- stitute good cause for setting aside the default judgment. For each factor you've found, identify the facts in our case, Brown v. Furlow, that would be helpful or harmful in estab- lishing that factor. If the facts of the cases provided are sufficiently different from our case, you can try to distinguish the case, explaining what arguments you think can be made not to use it if it would be harmful to our case. Also, if the facts are different but could be helpful, you should explain why, even with different facts, it should be controlling in our case. When you're reading the two cases provided to you, please remember you're trying to determine the state of the law from the information provided in the cases. Don't look up any additional law and don't cite any case law used by the judges writing these opinions as authority. Use only these cases and statutes as your authority The cases and statutes you should use should be cited as follows: Perry v. Central Bank & Trust, 812 S.W.2d 166 (Ky. Ct. App. 1991) Green Seed Co., Inc. v. Harrison Tobacco Storage Warehouse, Inc. 663 S.W.2d 755 (Ky. Ct. App. 1984) ky. Civ. R. 6.01; Ky. Civ. R. 55.02, and Ky. Civ. R. 60.02 Here are some tips for writing the memorandum: Use the format shown in Figure 7. Follow the format described in your Legal Writing study unit. Avoid long words and legal jargon. Don't overdo it-be brief and to the point, but thorough. Write in the active voice as much as you can. Check for errors of spelling, punctuation, and format Be sure to include precedent using the four cases and civil rules given. Cite only these four cases and civil rules Proofread and make your final editing review from a paper copy, not directly from the computer screen. Memo To: From: Supervising Attorey Paralegal [Fill in today's date] Brown v. Furlow, 04-CV-5887 Date: Re: Our File No. 5-987 Statement of Facts: Question(s) Presented: Answer: Discussion: Conclusion: FIGURE 7-Memo Format TAX ASSESSORS' OFFICE HEARING NOTICE Office of the Tax Assessors of Lackawanna County County Office Building 211 Ace Road 5th Floor Clark, Pennsylvania 18111 Jane P. Smith 123 Rock Road, Clark, Pennsylvania 18118 Taxpayer: Property Location: Tax Map No.: Date of Hearing: Time of Hearing: 19-19-050-019-8 March 6, 2018 10:35 a.m. FIGURE 2Hearing Notice Law Offices of Eliza Smith and Associates 5678 Barrister Row Clark, Pennsylvania 18112 (771) 333-4444 Fax (771) 333-4445 (Date) (Client Name) (Client Address) RE: Dear Very truly yours, CC FIGURE 3Sample Letterhead EXERCISE 3. WRITING AN INTERNAL MEMO For this exercise you'll write an internal office memorandum to your supervising attorney that advises her of the results of your research on a given topic and applies the law to the facts in your case. Remember, for an internal office memo, your purpose is to inform your supervising attorney as to what your research has found, not to persuade the reader one way or another Fact Scenario John Brown sued his dentist, Dr. Thomas Furlow, claiming he was injured because of Dr. Furlow's failure to extract an infected tooth on August 3, when he was examined by Dr. Furlow. After his appointment with Dr. Furlow, ignoring Dr. Furlow's recommendation to return because his tooth was infected, Brown left to go on vacation. While he camped in the desert, his tooth became more severely infected. The infection spread, causing him severe pain and fever and endangering his life. Brown passed out in the desert and was found by a passerby, who rushed him to the hospital. His life was saved, but he incurred significant medical expense, loss of income, and pain and suffering. Furlow was served with a complaint on March 1. The summons stated that he had 20 days to file an answer or that judgment could be entered against him. Furlow took the complaint home with him and put it in the safe in his study. Later, he phoned his attorney, who asked him when he had been served and made an appointment for March 19. On Thursday, March 18, Furlow's house was robbed and the contents of the safe, along with money and jewelry, were taken. Fearing for the safety of his wife and children, Furlow took his family and went to his mother-in-law's residence, approximately four hours away. He forgot the appointment with his attorney that morning and spent the weekend with his family at his mother-in-law's residence Upon his return on Monday, March 22, Dr. Furlow rescheduled his appointment with his attorney for March 23. Meanwhile, on March 23, a default judgment was entered against Furlow. Furlow's attorney phoned the court clerk the afternoon of March 23 and was told that a default judgment had been entered. He immediately filed a motion to set aside the default judgment. You're Dr. Furlow's attorney's paralegal and are instructed to review the two cases she believes are on point in this case and the applicable statutes. After reading the material, prepare a memorandum explaining whether they're applicable, favorable or unfavorable, and how they relate to the facts in this case. CASES CASE #1 AUBREY H. PERRY, JR. and CHRISTINE PERRY, f/k/a Christine P. Robey, APPELLANTS V. CENTRAL BANK & TRUST COMPANY, APPELLEE No. 90-CA-603-MR Court of Appeals of Kentucky 812 S.W.2d 166 March 29, 1991, Rendered PRIOR HISTORY: Appeal from Fayette Circuit Court: Honorable Rebecca Overstreet. Judge: Action No. 89-CI-2021. DISPOSITION: AFFIRMING. COUNSEL: ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANTS: Winifred L. Bryant, Lexington, Kentucky ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE: Joni D. Tackett, Earl S. Wilson, Jr., Lexington, Kentucky. JUDGES: Emberton, Howerton, and Miller, Judges. All concur. OPINION BY: HOWERTON OPINION: HOWERTON, JUDGE. Aubrey Perry (Perry) and Christine P. Robey (Christine) appeal from a default judgment entered in favor of Central Bank & Trust Company (Central Bank). Perry contends that the trial court erred (1) in finding that it had personal jurisdiction over him, (2) in granting the default judgment, and (3) in denying the post-judgment motions. Christine concedes the issue of jurisdiction as to her, but relies on the latter two issues on appeal. We affirm, This action began when Padgett Construction Company filed suit to enforce a mechanics' and materialmen's lien in the amount of $5,416.73 for improvements to the residence of Christine and Frederick Robey (Robey). That complaint was filed on June 22, 1989, against Robey, his wife Christine, Citizens Fidelity Bank & Trust Company of Lexington (Citizens), and Central Bank Citizens held the first mortgage on the property in the principal amount of $125,000. Central Bank held a second mortgage on the same property as security for a loan to Robey and Christine in the principal amount of $500,000. That mortgage note was executed on June 29, 1987, and provided that Robey and Christine were jointly and severally liable on the note. In addition, the note was secured by a deed of trust to some property in Virginia Beach, Virginia. The note was payable in equal monthly installments of $5,311.75, with a balloon payment of the balance due on or before June 29, 1988. Although no mention is made in the note as to the purpose of the loan, it was used to acquire an interest in Bristol's Restaurant in Lexington, Kentucky. On June 8, 1987, Christine's father, Aubrey Perry, signed a guaranty agreement in which he agreed to be liable up to $135,000 for any indebtedness of Christine and Robey to Central Bank incurred on or before June 30, 1988. This agreement began, "For good and valuable consideration, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, and in order to induce Central Bank & Trust Co to extend credit to Frederick R. Robey and Christine Robey.... This agreement was mailed to Perry, a Virginia resident, in Virginia, where it was signed and then it was mailed back to Central Bank. A few months later, Christine and Robey also signed another note in the principal amount of $65,000, due and payable in full on or before April 4, 1988. This note was secured by assignment of a sales contract for $350,000 on the Virginia Beach property, and the parties have treated this note as if it were also secured by the guaranty agreement, presumably because of the language in the latter concerning liabilities incurred on or before June 30, 1988. Christine and Robey managed to reduce the principal owed to Citizens on the first mort- gage to some $96,760, and they paid the other two notes down to $209,977.43 and $20,000, respectively. At some point, Robey and Christine separated and divorced, and Christine moved back to Virginia. As mentioned, suit was begun to enforce the construc- tion liens and the residence was subject to foreclosure sale. Because of the guaranty agreement, Central Bank sought to join Aubrey Perry as a third-party defendant by motion made July 19, 1989. This motion was granted on August 7, 1989. The house was ultimately sold by private sale for $185,000. The first mortgage to Citizens was satisfied, and Central Bank received $70,306.70 from the proceeds toward satisfaction of its sec- ond mortgage. Thus, approximately $162,000 of the principal remained owing from the two promissory notes. Central Bank sought to collect the debt from Robey, Christine, and/or Perry. When the three failed to file answers to Central Bank's cross-claim within 20 days. CR 12.01, the bank filed a motion for default judgment on October 10, 1989. Robey then answered by informing the court that he had filed for protection under the federal bankruptcy laws on October 9, 1989. Christine filed a notice of entry of appearance on October 20, 1980, and Perry filed a notice of special entry of appearance on the same day, both filed affidavits and a response to the motion for default judgment. The trial court granted the default judgment against Christine and Perry on November 16, 1989, and postjudgment motions were filed PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 LEGAL WRITING PROJECT 1 PAGE 2 on November 27, 1989, including a motion pursuant to CR 52.02 for findings of fact and conclusions of law regarding the question of personal jurisdiction over Perry. A hearing was held on the motions and all were denied by order entered March 14, 1990. That order stated that the court had personal jurisdiction over Perry pursuant to KRS 454.210. It is from the entry of default judgment that Christine and Perry bring this appeal Perry challenges the trial court's assertion of jurisdiction because he was never in Kentucky concerning the guaranty note, his signature was solicited by the bank, and the note was sent to him in Virginia where he signed it and mailed it back to the bank. Our long-arm statute is KRS 454.210, and it is designed to permit the exercise of per- sonal jurisdiction over nonresident defendants while complying with federal constitutional requirements of due process. Texas American Bank v. Sayers, 674 S. W. 2d 36, 38 (Ky. App. 1984), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1211, 105 S. Ct 1180, 84 L. Ed.2d 328 (1985). Kentucky's long-arm statute allows its courts to reach to the full constitutional limits of due process in entertaining jurisdiction over nonresident defendants. Mohler v. Dorado Wings Inc., 675 S.W.2d 404 405 (Ky. App. 1984). Due process requires that a nonresident defendant have certain minimum contacts with the forum state "such that the mainte- nance of the suit does not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice." International Shoe Co. v. State of Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316,66 S. Ct. 154, 158, 90 L. Ed. 95 (1945), quoting Milliken v. Meyer, 311 U.S. 457, 463, 61 S. Ct. 339, 343, 85 L Ed. 278 (1940): see also Mohler, 675 S.W.2d at 405. To determine the outer limits of per- sonal jurisdiction based on a single act, the following three-part test has been put forth: First, the defendant must purposefully avail himself of the privilege of acting in the forum state or causing a consequence in the forum state. Second, the cause of action must arise from the defendant's activities there. Finally, the acts of the defen- dant or consequences caused by the defendant must have a substantial enough connection with the forum state to make the exercise of jurisdiction over the defen- dant reasonable. Southern Machine Co. v. Mohasco Industries, Inc., 401 F 2d 374 381 (6th Cir. 1968). citing McGee v. International Life Insurance Co., 355 U.S. 220,78 S. Ct. 199, 2L Ed.2d 223 (1957), and Hanson v Denckla, 357 U.S. 235, 78 S. Ct. 1228, 22. Ed. 2d 1283 (1958). The statute itself reads in pertinent part: (2)(a) A court may exercise personal jurisdiction over a person who acts directly or by an agent, as to a claim arising from the person's: 1. Transacting any business in this Commonwealth: (3) (a) When personal jurisdiction is authorized by this section, service of process may be made on such person, or any agent of such person, in any county in this Commonwealth, where he may be found, or on the secretary of state who, for this purpose, shall be deemed to be the statutory agent of such person KRS 454 210 A case which this Court found helpful, but which was not cited by either party is National Can Corp. v. K Beverage Co., 674 F.2d 1134 (6th Cir. 1982). In that case, a North Dakota resident, who never set foot in Kentucky, was subject to personal jurisdiction in this state by the signing of a personal guaranty agreement in North Dakota. The nonresident's husband was a vice president and shareholder of a company whose principal place of business was Louisville. Her only relationship with Kentucky was the signing of the agreement and her marital interest in her husband's stock in the company. The company failed, and she and other guarantors were sued in federal district court. The court found that the three-part test of Southern Machine, supra, was met by all guar- antors involved. The court stated that the defendants voluntarily signed the agreements, without which credit would not have been furnished.- 674 F.2d at 1137, and the guaran- tors knew the business was to be located in Kentucky. "Signing a personal guaranty for a Kentucky business in which one has an economic interest is the sort of conduct and con- nection with the forum state that makes it reasonable to anticipate being haled into court there when the underlying contract is breached." National Can, supra, 674 F2d at 1138, quoting World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286, 287, 100 S. Ct. 569. 562, 62 L. Ed. 2d 490 (1980). The court determined that the guaranties were essential for the startup of the enterprise and that they constituted "the sort of purposeful act contem- plated in Southern Machine." 674 F.2d at 1138 The court in National Can also found that the second prong of the test was met because the agreements were the basis for the action. 674 F.2d at 1138. The court then concluded that there was sufficient connection with the forum state to make the exercise of jurisdic- tion reasonable, reciting that the guarantors voluntarily signed the agreements, Kentucky was chosen as the business situs, the guaranties were vital to the establishment of the business, and the operation had a realistic impact on the commerce of Kentucky. Id. Comparing the facts of National Can to the present case, we find several similarities. While he may not have sought out Central Bank, Perry's act of signing the guaranty cer- tainly caused a consequence in this state, because the $500,000 would not have been loaned to Perry's daughter and Robey had it not been for Perry's signature on the guar- anty. See National Can, 674 F2d at 1137. The agreement also provided that it shall be "in all respects governed, construed, applied and enforced in accordance with the laws of (Kentuckyl. Although not an explicit consent to jurisdiction, this language put Perry on notice that he could expect any legal ramifications to be dealt with in Kentucky Furthermore, Perry's agreement was the basis for the loan and acquisition of the interest in Bristol's, cf. National Can, 674 F.2d at 1138, and so the cause of action arose from his act of guaranteeing the note. Perry's act of signing the agreement also had a substantial enough connection with Kentucky to make personal jurisdiction reasonable. He knew that he was guarantee ing loans extended in this state for his son-in-law to acquire an interest in a business here, and he also knew that should Christine and Robey fail to make payments or if the business venture failed, he would be looked to for payment. While he did not acquire any economic interest in the business himself, he certainly had a stake in its success. The court in Davis H. Elliott Co. v. Caribbean Utilities Co., 513 E2d 1176 (6th Cir. 1975) stated at 1182: The purposeful action test of Southern Machine. is not intended to require that to be subject to the personal jurisdiction of the courts of a state, a nonresident cor- poration must actively conduct an income generating enterprise in that state. To the contrary, it is designed only to insure that the defendant has become involved with the forum state through actions freely and intentionally done. in-Flight Devices Corp. v. Van Dusen Air, Inc., 466 F 20 220, 228 (6th Cir. 1972), We believe the trial court correctly concluded that Perry had sufficient minimum contacts with Kentucky to satisfy due process requirements for personal jurisdiction. Next, we turn to Perry and Christine's second allegation that the trial court erred in grant- ing default judgment. CR 55.02 provides that a court may set aside a default judgment in accordance with CR 60.02 for good cause shown. Factors to consider in deciding whether to set aside a judgment are: (1) valid excuse for default, (2) meritorious defense, and (3) absence of prejudice to the other party. 7 W. Bertelsman and K. Philipps. Kentucky Practice, CR 55.02, comment 2 (4th ed. 1984) (hereinafter "Ky. Prac."). Christine signed for the service of process of the lawsuit, but stated that she talked with her former attomey who, as Christine recalls, advised her that she did not think she had any assets. Based on this advice, Christine made no response to the summons. "Carelessness by a party or his attorney is not reason enough to set an entry aside." 7 Ky. Prac. CR 55.02, comment 2. Perry signed for the motion seeking to add him as a party to the original suit, and his housekeeper signed for the actual summons once he became a party. This was accomplished in July and in early September 1989. Perry states that he had no knowledge of the suit until he received the motion for default judg- ment on October 12, 1989. Furthermore, both Christine and Perry wrote letters in August agreeing to the private sale of the Robey residence. This should have put them on notice that should there not be enough money realized from the sale, the entire mortgage would not be satisfied and this might open them up for some liability. We believe the parties did not exercise due diligence concerning this suit and answering the summons. Furthermore, the apparent defenses which might alter the outcome are also weak. Christine and her father both assert that Central Bank misrepresented the extent of the interest Robey was acquiring. Christine and Perry claim that they believed Robey was acquiring interests in two Louisville restaurants and a meat packing company in Lexington as well, for the $500,000. Central Bank merely wanted security for its loan to Robey and Christine. The bank was not concerned with whether Robey was acquiring an interest in one restaurant or three: its only concern was that the borrower be able to pay the loan, or in the alternative, that there be adequate security in the event of default. It is true that courts do not favor default judgments and that it is preferable to decide cases on the merits. Dressler v Barlow, 729 S.W.2d 464, 465 (Ky. App. 1987). If it appeared that Christine and Perry had a truly mentorious defense, then on balance, whether the trial court should have set the judgment aside would be a close call. However, we believe the excuses for failing to answer are weak, as are the defenses. and we cannot say it was an error or abuse of discretion for the trial court either to grant the default judgment or to refuse to set it aside. The judgment and order of the Fayette Circuit Court are affirmed. AFFIRMING CASE #2 GREEN SEED COMPANY, INC., APPELLANT V. HARRISON TOBACCO STORAGE WAREHOUSE, INC., APPELLEE No. 82-CA-2468-MR Court of Appeals of Kentucky 663 S.W.2d 755 January 27, 1984 APPEAL FROM HARRISON CIRCUIT COURT, HONORABLE JOHN P. LAIR, JUDGE. CIVIL ACTION NO. 81-Cl-184 DISPOSITION: AFFIRMING COUNSEL: Attorney For Appellant: William C. Shouse, Shouse & Burrus, Lexington, Kentucky Attorney For Appellee: David E. Melcher, Swinford & Sims, Cynthiana, Kentucky. JUDGE: Hayes, Chief Judge. OPINION BY: HAYES OPINION: This appeal arises from a refusal to set aside a default judgment by the Harrison Circuit Court. The appellee entered into a lease agreement with the appellant on May 16, 1979. The appellee filed suit against the appellant on September 28, 1981. seeking judgment for the entire rental payment due under the lease. On October 23. 1981, the appellant filed a petition for removal in the United States District Court, properly served the appellee and filed a copy with the Harrison Circuit Court. This petition was dismissed as defective on October 27, 1981. Instead of amending this petition, the appellant filed a second petition for removal on November 5, 1981, longer than thirty days after the filing of the complaint. Neither the appellee nor the Harrison Circuit Court received notice or copy of this petition, although the appellant offered affidavits that notice and copy were mailed. On January 27. 1982, the appellee applied for a default judgment because of the appellant's failure to plead or otherwise defend the action. The appellant had made no answer in the trial court where both the appellee and the trial court thought the action to be because of the aforemen- tioned failure in notice. The appellant also had made no answer or defense in the United States District Court where he thought the action to be. On February 5, 1982, the trial court granted and entered the default judgment. The appellant appeared and made a motion to set aside the default judgment on February 16, 1982, because the second petition for removal had not been remanded. Prior to ruling on this motion, the United States District Court, on April 1, 1982, dismissed the second petition for removal as being defective. The appellant, then asked the trial court for leave to file an answer and counterclaim and to amend its motion to set aside the default judgment. On August 6, 1982, the trial court denied the motion to set aside the judgment. The issue before this Court is whether the trial court abused its discretion in failing to set aside the default judgment. The law clearly disfavors default judgments. Bargo v. Lewis, 305 S.W.2d 757 (Ky 1957). Moreover, the trial court has wide discretion to set aside a default judgment. Northcutt v. Nicholson, 246 Ky. 641, 55 S.W.2d 659 (1932). The moving party, however, cannot have the judgment set aside and achieve his day in court if he cannot show good cause and a meritorious defense. CR 55.02. Jacobs v. Bell, 441 S.W.2d 448 (Ky, 1969). Good cause is most commonly defined as a timely showing of the circumstances under which the default judgment was procured. The appellant asserts that his reliance on the removal of the trial court's jurisdiction to the United States District Court is a sufficient showing of good cause. This Court does not agree. Federal, not state, law governs all removal proceedings. Grubbs v. General Electric Credit Corp., 405 U.S. 699, 31 L. Ed.2d 612, 92 S. Ct. 1344 (1972). Removal of juris diction is effected after the movant files a petition and bond, gives notice to all adverse parties, and files a copy of the petition with the clerk of the state court. 28 U.S.C. $ 1446(e). Once these steps are completed, the state court loses jurisdiction over the case unless and until the case is remanded by the federal court. Id. The removal is effec tive the date of the petition. Howes v. Childers, 426 F Supp. 358 (WD. Ky 1977 Wright, Miller & court retains its jurisdiction until it is notified of the removal petition, this procedure allows an interim period between the filing of the petition and the notice to the parties and the state court where the federal and state courts both have jurisdiction. Berberian v. Gibney, 514 F.2d 790 (1st Cir. 1975). Howes, supra. Dual jurisdiction remained in the instant case at least until February 16, 1982, when the appellant's motion to set aside the default judgment first notified the appellee and the trial court of the second petition for removal. See Medrano v. State of Texas, 580 F.2d 803 (5th Cir. 1978). Where no notice, actual or constructive, is given to the state court, the trial court's actions are not void. ld. Obviously. conflicting actions can occur. Most courts find concurrent jurisdiction means nothing more than that once the state court is notified of the removal, federal jurisdiction predominates in any conflicting actions during this interim period. 1A Moore's Federal Practice 0.168 [-3-8) (1983). Howes, supra; contra; Wright 3737. In effect, then, the federal court can overturn any default judgment that had been granted during the period of dual jurisdiction. Id. Where, as in the case at bar, the federal court dismisses the petition, the removing party's only recourse is a motion to set aside the judgment, and reliance on his petition for removal as good cause may fail. When the removing party fails to answer in compliance with either CR 12.01 or Fed. R. Civ. P. 81, the trial court does not abuse its discretion in finding such reliance inadequate as good cause. CR 12.01 requires a defendant to serve his answer within twenty (20) days after service of the summons upon him. The appellant waited almost seven (7) months before he served the appellee with his answer. The default judgment was not granted until over three (3) months had elapsed after the time the appellant was required to tender his answer. The appellant's failure to file a timely answer is sufficient basis for a default judg- ment, and the appellant is not entitled to have the judgment set aside unless he can show reasonable excuse for the delay in answering and establish that he is not guilty of unrea- sonable delay. CR 55.01; Terrafirma, Inc. v. Krogdahl, 380 S.W.2d 86 (ky. 1964). The appellant's assertion that he believed the case had been removed is an unreason- able excuse when he has not complied with Fed. R. Civ. P. 81. This rule attempts to resolve the potential conflicts between the thirty (30) days allowed for removal under 28 U.S.C.S 1446, the twenty days allowed for an answer under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12, and the various times allowed for answers under state rules by providing. In a removed action in which the defendant has not answered, he shall answer or present the other defenses or objections available to him under these rules within 20 days after the receipt through service or otherwise of a copy of the initial plead- ing setting forth the claim for relief upon which the action or proceeding is based, or within 20 days after service of summons upon such initial pleading, then filed, or within 5 days after the filing of the petition for removal, whichever period is longer Fed. R. Civ. P. 81(c). The removing party, then, can wait until the longer of twenty (20) days after service or summons or five (5) days after the removal petition to answer the complaint and need not comply with state rules. The party, however, must answer. The appellant's failure to answer pursuant to this rule belies his reliance on the removal pro- ceedings and precludes his using this reliance as an excuse for delay. The appellant's reply brief suggests that good cause is further established because notice of the February 5. 1982 hearing was required by CR 55.01 and he received no notice. The record presents conflicting evidence as to whether the appellant received notice of the hearing. CR 55.01, however, requires noti only when the party has made an appearance before the court. Pound Mill Coal Co. v. Pennington, 309 S.W.2d 772 (Ky. 1958). While appellant argues the filing of the first petition for removal is an appearance, he has not appeared. The general rule of law holds that in the federal or state courts a petition for the removal of a cause to a federal court and the proceedings thereon do not constitute an appearance which waives jurisdictional objections or prevents defendant from being in default for want of appearance." 6 CJ.S. Appearances $ 32 (1975). The word "appeared in CR 55.01 means the defendant has so participated in the action as to indicate an intention to defend. Smith v. Gadd, 280 S.W.2d 495 (Ky. 1955). The appellant's failure to answer in any court for seven months contradicts any intention to defend and makes unnecessary the resolution of whether the appellant received notice. The trial court did not abuse its discretion in finding the appellant failed to show good cause. His failure to show good cause obviates any need for this court to determine whether the appellant presented a meritorious defense. The judgment is affirmed. ALL CONCUR. STATUTES Kentucky Civil Rule 6.01. Computation In computing any period of time prescribed or allowed by these rules, by order of court or by any applicable statute, the day of the act, event or default after which the designated period of time begins to run is not to be included. The last day of the period so computed is to be included, unless it is a Saturday, a Sunday or a legal holiday, in which event the period runs until the end of the next day which is not a Saturday, a Sunday or a legal holiday. When the period of time prescribed or allowed is less than seven days, intermediate Saturdays, Sundays and legal holidays shall be excluded in the computation. Kentucky Civil Rule 55.02. Setting Aside Default For good cause shown the court may set aside a judgment by default in accordance with Rule 60.02. Kentucky Civil Rule 60.02. Mistake; inadvertence; excusable neglect; newly discov. ered evidence; fraud; etc. On motion a court may, upon such terms as are just, relieve a party or his legal rep- resentative from its final judgment, order, or proceeding upon the following grounds: (a) mistake, inadvertence, surprise or excusable neglect; (b) newly discovered evi- dence which by due diligence could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial under Rule 59.02: (c) perjury or falsified evidence; (d) fraud affecting the proceedings, other than perjury or falsified evidence; (e) the judgment is vold, or has been satisfied, released, or discharged, or a prior judgment upon which it is based has been reversed or otherwise vacated, or it is no longer equitable that the judg- ment should have prospective application; or (1) any other reason of an extraordinary nature justifying relief. The motion shall be made within a reasonable time, and on grounds (a), (b), and (c) not more than one year after the judgment, order, or pro- ceeding was entered or taken. A motion under this rule does not affect the finality of a judgment or suspend its operation. TIPS As you're reading each case and statute, consider what factors must be shown to con- stitute good cause for setting aside the default judgment. For each factor you've found, identify the facts in our case, Brown v. Furlow, that would be helpful or harmful in estab- lishing that factor. If the facts of the cases provided are sufficiently different from our case, you can try to distinguish the case, explaining what arguments you think can be made not to use it if it would be harmful to our case. Also, if the facts are different but could be helpful, you should explain why, even with different facts, it should be controlling in our case. When you're reading the two cases provided to you, please remember you're trying to determine the state of the law from the information provided in the cases. Don't look up any additional law and don't cite any case law used by the judges writing these opinions as authority. Use only these cases and statutes as your authority The cases and statutes you should use should be cited as follows: Perry v. Central Bank & Trust, 812 S.W.2d 166 (Ky. Ct. App. 1991) Green Seed Co., Inc. v. Harrison Tobacco Storage Warehouse, Inc. 663 S.W.2d 755 (Ky. Ct. App. 1984) ky. Civ. R. 6.01; Ky. Civ. R. 55.02, and Ky. Civ. R. 60.02 Here are some tips for writing the memorandum: Use the format shown in Figure 7. Follow the format described in your Legal Writing study unit. Avoid long words and legal jargon. Don't overdo it-be brief and to the point, but thorough. Write in the active voice as much as you can. Check for errors of spelling, punctuation, and format Be sure to include precedent using the four cases and civil rules given. Cite only these four cases and civil rules Proofread and make your final editing review from a paper copy, not directly from the computer screen. Memo To: From: Supervising Attorey Paralegal [Fill in today's date] Brown v. Furlow, 04-CV-5887 Date: Re: Our File No. 5-987 Statement of Facts: Question(s) Presented: Answer: Discussion: Conclusion: FIGURE 7-Memo Format TAX ASSESSORS' OFFICE HEARING NOTICE Office of the Tax Assessors of Lackawanna County County Office Building 211 Ace Road 5th Floor Clark, Pennsylvania 18111 Jane P. Smith 123 Rock Road, Clark, Pennsylvania 18118 Taxpayer: Property Location: Tax Map No.: Date of Hearing: Time of Hearing: 19-19-050-019-8 March 6, 2018 10:35 a.m. FIGURE 2Hearing Notice Law Offices of Eliza Smith and Associates 5678 Barrister Row Clark, Pennsylvania 18112 (771) 333-4444 Fax (771) 333-4445 (Date) (Client Name) (Client Address) RE: Dear Very truly yours, CC FIGURE 3Sample Letterhead

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts