An understanding of the nature of Enrons questionable transactions is fundamental to understanding why Enron failed. What

Question:

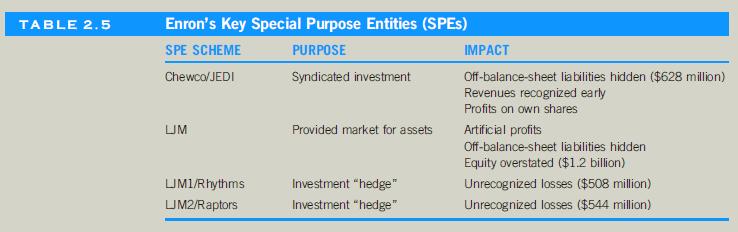

An understanding of the nature of Enron’s questionable transactions is fundamental to understanding why Enron failed. What follows is an abbreviated overview of the essence of the major important transactions with the SPEs, including Chewco, LJM1, LJM2, and the Raptors. A much more detailed but still abbreviated summary of these transactions is included in the Enron’s Questionable Transactions Detailed Case in the digital archive for this book at www.cengagebrain.com.

Enron had been using specially created companies called SPEs for joint ventures, partnerships, and the syndication of assets for some time. But a series of happenstance events led to the realization by Enron personnel that SPEs could be used unethically and illegally to do the following:

• Overstate revenue and profits

• Raise cash and hide the related debt or obligations to repay

• Offset losses in Enron’s stock investments in other companies

• Circumvent accounting rules for valuation of Enron’s Treasury shares

• Improperly enrich several participating executives

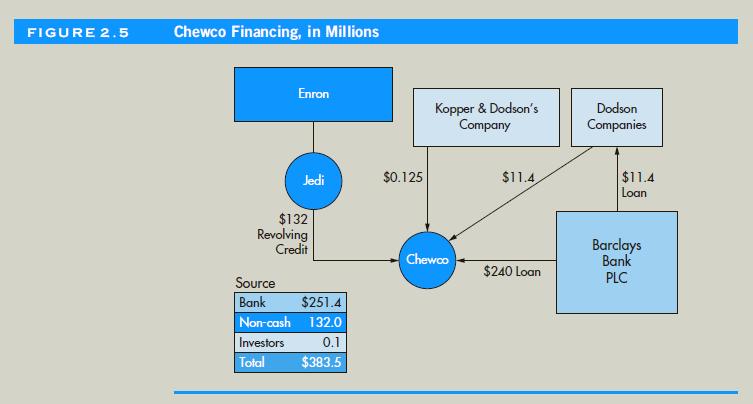

• Manipulate Enron’s stock price, thus misleading investors and enriching Enron executives who held stock options In November 1997, Enron created an SPE called Chewco to raise funds or attract an investor to take over the interest of Enron’s joint venture investment partner, CalPERS,1 in an SPE called Joint Energy Development Investment Partnership (JEDI). Using Chewco, Enron had bought out CalPERS interest in JEDI with Enron-guaranteed bridge financing and tried to find another investor.

Enron’s objective was to find another investor, called a counterparty, which would do the following:

• Be independent of Enron

• Invest at least 3% of the assets at risk

• Serve as the controlling shareholder in making decisions for Chewco Enron wanted a 3%, independent, controlling investor because U.S. accounting rules would allow Chewco to be considered an independent company, and any transactions between Enron and Chewco would be considered at arm’s length. This would allow “profit” made on asset sales from Enron to Chewco to be included in Enron’s profit even though Enron would own up to 97% of Chewco.

Unfortunately, Enron was unable to find an independent investor willing to invest the required 3% before its December 31, 1997, year end. Because there was no outside investor in the JEDI-Chewco chain, Enron was considered to be dealing with itself, and U.S. accounting rules required that Enron’s financial statements be restated to remove any profits made on transactions between Enron and JEDI. Otherwise, Enron would be able to report profit on deals with itself, which, of course, would undermine the integrity of Enron’s audited financial statements because there would be no external, independent validation of transfer prices. Enron could set the prices to make whatever profit it desired and manipulate its financial statements at will.

That, in fact, was exactly what happened.

When no outside investor was found, Enron’s CFO, Andrew Fastow, proposed that he be appointed to serve as Chewco’s outside investor. Enron’s lawyers pointed out that such involvement by a high-ranking Enron officer would need to be disclosed publicly, and one of Fastow’s financial staff—a fact not shared with the board—Michael Kopper, who continued to be an Enron employee, was appointed as Chewco’s 3%, independent, controlling investor, and the chicanery began.

Enron was able to “sell” (transfer really)

assets to Chewco at a manipulatively high profit. This allowed Enron to show profits on these asset sales and draw cash into Enron accounts without showing in Enron’s financial statements that the cash stemmed from Chewco borrowings and would have to be repaid. Enron’s obligations were understated—they were “hidden” and not disclosed to investors........

Questions:-

1. Enron’s directors realized that Enron’s conflict of interests policy would be violated by Fastow’s proposed SPE management and operating arrangements, and they instructed the CFO, Andrew Fastow, as an alternative oversight measure, endure that he kept the company out of trouble. What was wrong with their alternatives?

2. Ken Lay was the chair of the board and the CEO for much of the time. How did this probably contribute to the lack of proper governance?

3. What aspects of the Enron governance system failed to work properly, and why?

4. Why didn’t more whistle-blowers come forward, and why did some not make a significant difference? How could whistle-blowers have been encouraged?

5. What should the internal auditors have done that might have assisted the directors?

6. What conflict-of-interest situations can you identify in the following?

• SPE activities • Executive activities 7. Why do you think that Arthur Andersen, Enron’s auditors, did not identify the misuse of SPEs earlier and make the board of directors aware of the dilemma?

8. How would you characterize Enron’s corporate culture? How did it contribute to the disaster?

Step by Step Answer:

Business And Professional Ethics

ISBN: 9781337514460

8th Edition

Authors: Leonard J Brooks, Paul Dunn