Henry Wells, William Fargo, and their partners decided the two business services most needed by San Franciscans

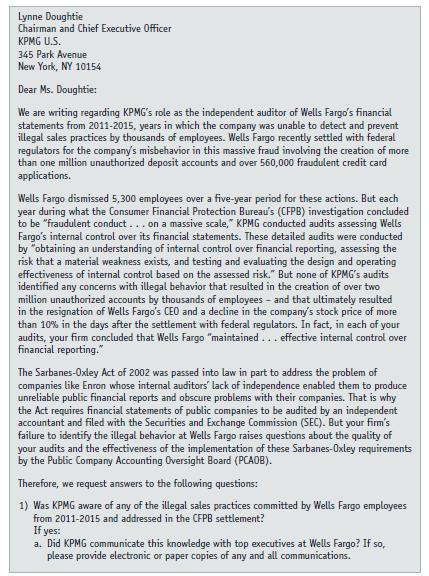

Question:

Henry Wells, William Fargo, and their partners decided the two business services most needed by San Franciscans were transportation and banking. After acquiring a building near the intersection of present-day California and Montgomery Streets, the new company plunged headfirst, if not blindly, into those lines of business. Despite the lack of considerable forethought-or a comprehensive business plan-hard work and ingenuity allowed Wells Fargo to thrive.Wells Fargo initially made a name for itself in the San Francisco Bay Area by providing rapid and reliable freight, courier, and mail delivery services. In the late 1850s, the company's founders helped organize the famous Butterfield Overland Mail Route that connected San Francisco with St. Louis. In a little more than three weeks, the company's stagecoaches could deliver mail, freight, and bone-weary travelers from the banks of the Mississippi River to the City by the Bay. Prior to the development of the first intercontinental railroad in 1869, Wells Fargo's fleet of six-horse stagecoaches served as the largest and most important transportation network west of the Mississippi River. (In 1862, the business assumed control of the iconic but short-lived Pony Express.) Wells Fargo's banking operations expanded more slowly than its transportation services. However, the federal government's decision to nationalize major interstate freight and transportation lines during World War I forced Wells Fargo to focus almost exclusively on the banking industry. An aggressive acquisition strategy and the success of other key strategic initiatives implemented by successive generations of opportunistic, if not freewheeling, senior executives made Wells Fargo the largest banking firm globally in terms of collective market value by 2015. At the time, the company operated nearly 9,000 retail branches in 35 countries and had over 70 million customers.In addition to its impressive size and unparalleled growth in the banking industry, Wells Fargo ranked, until recently, among the most admired and respected companies in both the United States and around the globe. In 2015, for example, Wells Fargo placed seventh in Barron's annual survey of the world's most respected multinational companies. Disaster struck in late 2016 when a federal agency revealed Wells Fargo had been fined $185 million for "unfair, deceptive, and abusive" banking practices. The resulting headline-grabbing scandal caused Wells Fargo to plummet to the bottom of Barron's annual survey.

Growth at All Costs During the early years of the twenty-first century, two strategic initiatives contributed heavily to Well Fargo's dramatic growth: a continually expanding product line of financial services and the "cross-selling" of those services to the company's existing customers. In fact, cross-selling eventually became the lynchpin of Wells Fargo's industry leading business model.

"Financial products per customer household" rates among the most important metrics in the retail banking industry. By 2013, Wells Fargo provided an average of 6.15 financial products to each of its customer households, four times greater than the industry average. A noted bank consultant reported that "Wells Fargo is the master of this . . . no other bank can touch them."1 The bank's long product line of services for retail consumers included checking and savings accounts, credit card accounts, automobile loans, student loans, retirement accounts, mortgage services, investment portfolio management services, among others.

Wells Fargo's cross-selling of its products was particularly successful from 2000 through 2013 when the company's financial-products-per-customer-household measure rose by approximately 50 percent. During this time frame, published reports in the Los Angeles Times and various business publications suggested that intense pressure imposed by Wells Fargo's branch managers on lower-level employees to reach unrealistic sales quotas accounted for the company's cross-selling success. The branch managers, themselves, also faced heavy pressure from Wells Fargo's regional managers and senior executives to reach or surpass the sales goals for their operating units each reporting period.

A 2013 Los Angeles Times article entitled "Wells Fargo's Pressure-cooker Sales Culture Comes at a Cost" prompted federal and local regulatory officials to begin investigating the company's marketing tactics. A former Wells Fargo entry-level employee quoted in the article recalled how superiors had belittled subordinates who failed to reach their assigned sales quotas. "We were constantly told we would end up working for McDonald's. If we did not make the sales quotas . . . we had to stay for what felt like after-school detention, or report to a call session [to telephone customers] on Saturdays."2 A former Wells Fargo branch manager reported that if his branch failed to reach its periodic sales goal, he was "severely chastised and embarrassed in front of 60-plus managers"3 from his sales region.

Questions

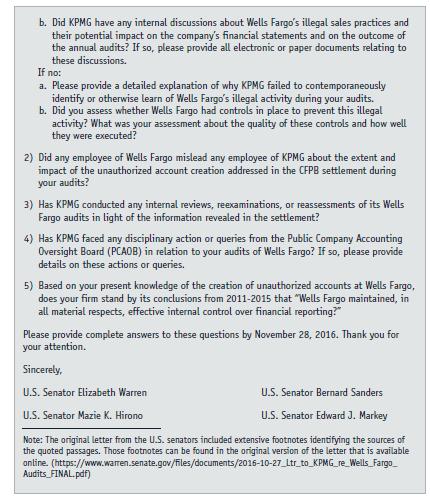

1. Identify the different types or classes of internal controls. How do internal controls over financial reporting (ICFR) differ from the other types or classes of internal controls?

2. Do you agree with KPMG's position that Wells Fargo's improper sales practices did not involve the company's ICFR? Defend your answer.

3. How does the AICPA's Auditing Standards Board define a material weakness in internal control? How does the PCAOB define a material weakness in ICFR? What factors should auditors consider in deciding whether an ICFR deficiency qualifies as a material weakness in ICFR?

4. Wells Fargo's independent board members concluded that the bank's "decentralized corporate structure" was "one root cause of the scandal." Do you believe the decentralized nature of Wells Fargo's corporate structure qualified as a "material weakness" in Wells Fargo's ICFR? Why or why not?

5. Does an audit firm of a public company have a responsibility to apply audit procedures intended to determine whether the client has committed illegal acts that don't directly impact its financial statements? Explain. What responsibility does an auditor of a public company have if the auditor discovers such illegal acts by the client?

6. While the Wells Fargo scandal was unfolding, several parties pointed out that KPMG had served as the company's audit firm since 1931. Explain how the length of an audit firm's tenure may influence its ICFR assessment for a public company client.

Step by Step Answer: