Question: Assembly language RaspberryPi This all the information which was provided and there is nothing else : Read the entire lab instruction before starting. This lab

Assembly language RaspberryPi

This all the information which was provided and there is nothing else :

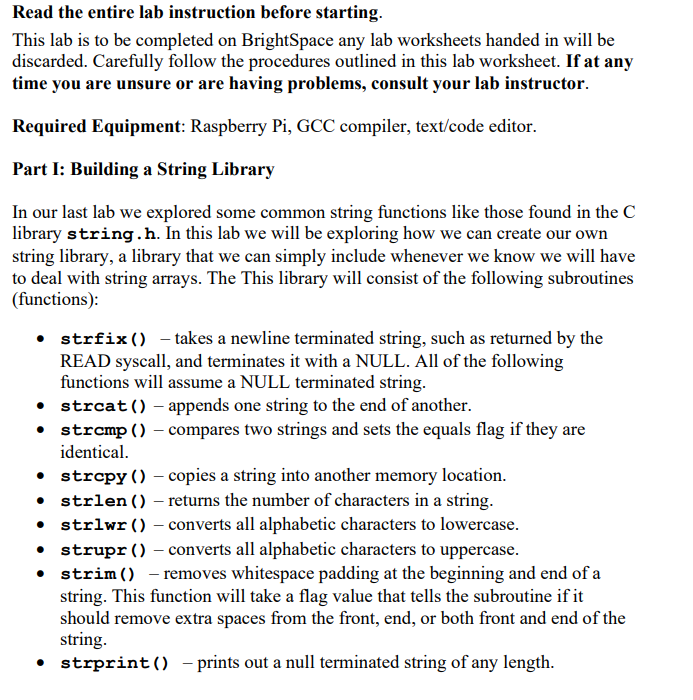

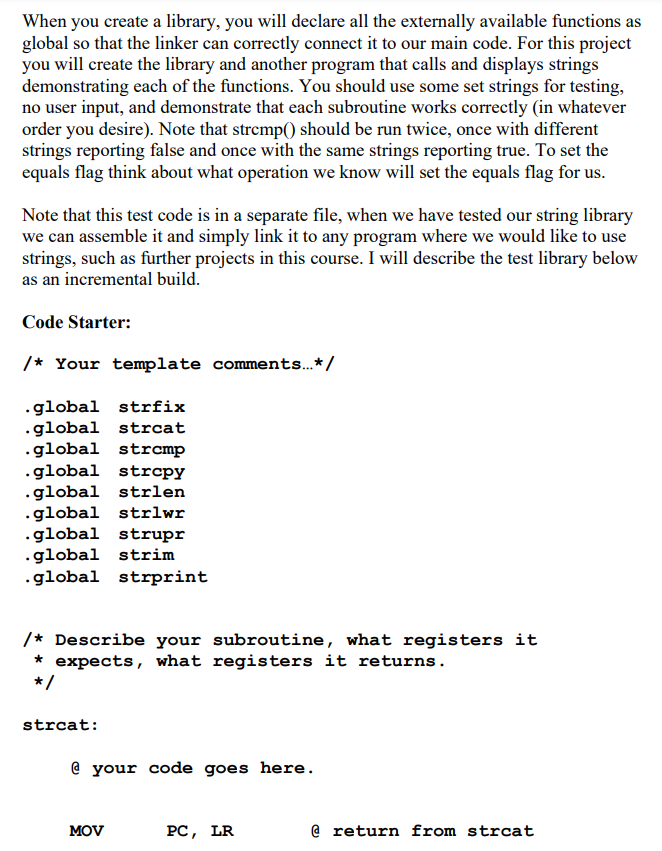

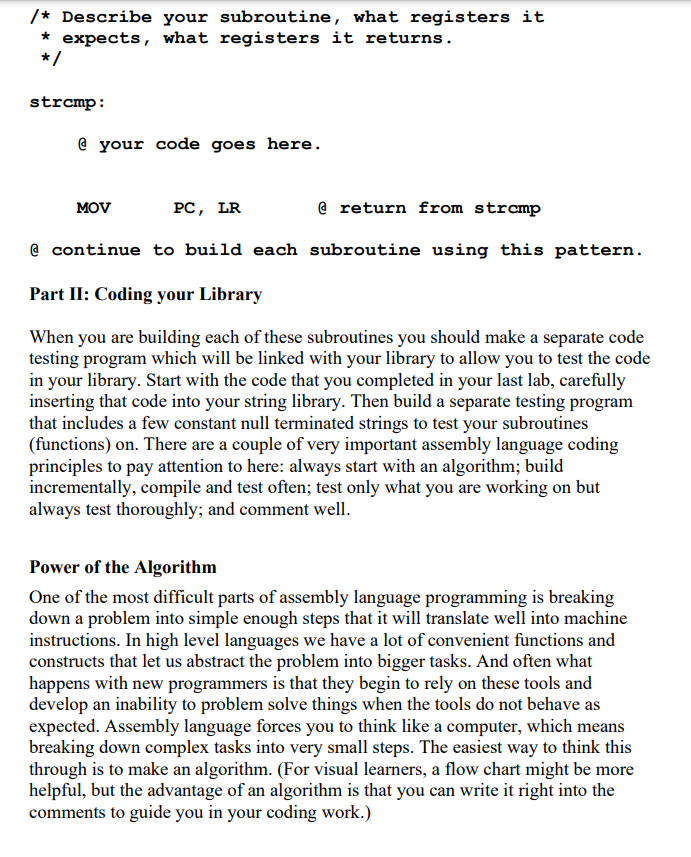

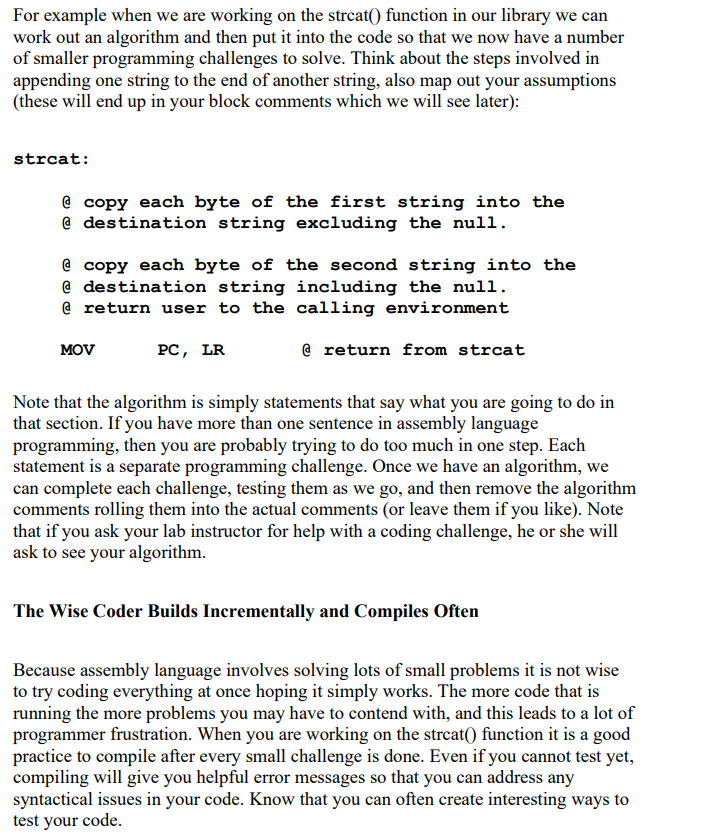

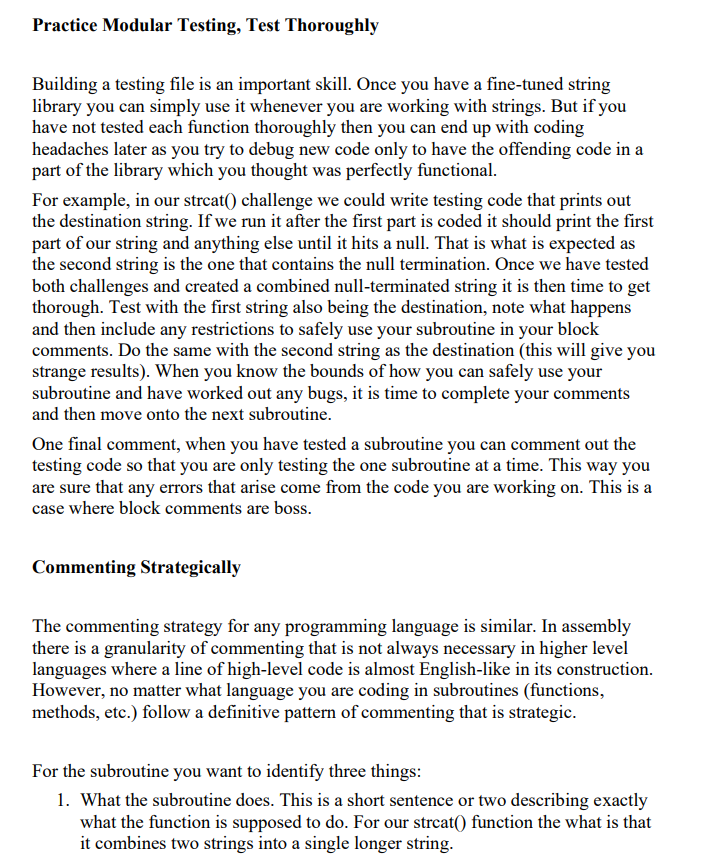

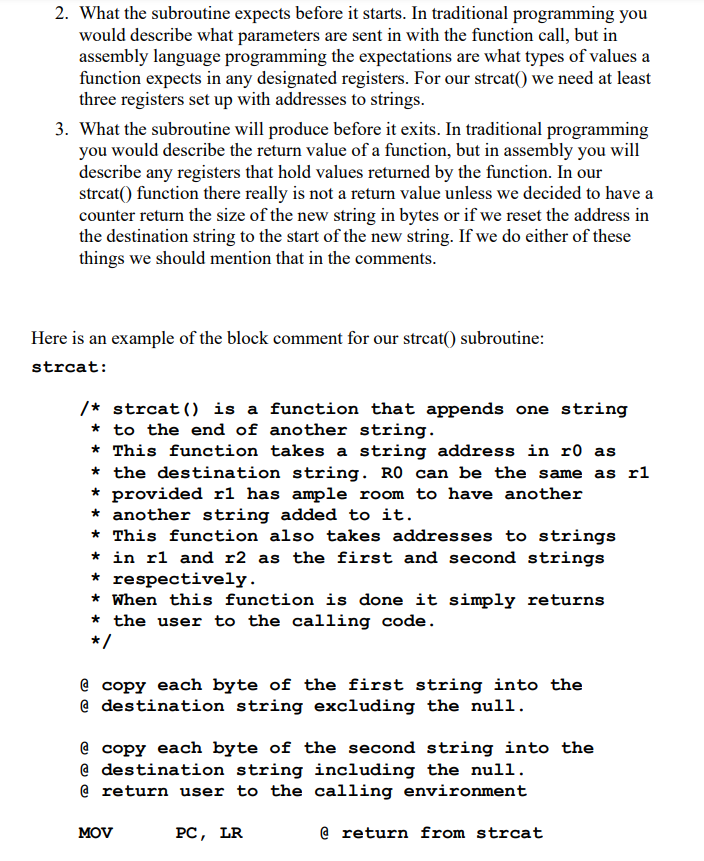

Read the entire lab instruction before starting. This lab is to be completed on BrightSpace any lab worksheets handed in will be discarded. Carefully follow the procedures outlined in this lab worksheet. If at any time you are unsure or are having problems, consult your lab instructor. Required Equipment: Raspberry Pi, GCC compiler, text/code editor. Part I: Building a String Library In our last lab we explored some common string functions like those found in the C library string.h. In this lab we will be exploring how we can create our own string library, a library that we can simply include whenever we know we will have to deal with string arrays. The This library will consist of the following subroutines (functions): strfix() takes a newline terminated string, such as returned by the READ syscall, and terminates it with a NULL. All of the following functions will assume a NULL terminated string. strcat() - appends one string to the end of another. strcmp() compares two strings and sets the equals flag if they are identical. strcpy() - copies a string into another memory location. strlen() returns the number of characters in a string. strlwr () - converts all alphabetic characters to lowercase. strupr() - converts all alphabetic characters to uppercase. strim() - removes whitespace padding at the beginning and end of a string. This function will take a flag value that tells the subroutine if it should remove extra spaces from the front, end, or both front and end of the string strprint() - prints out a null terminated string of any length. When you create a library, you will declare all the externally available functions as global so that the linker can correctly connect it to our main code. For this project you will create the library and another program that calls and displays strings demonstrating each of the functions. You should use some set strings for testing, no user input, and demonstrate that each subroutine works correctly in whatever order you desire). Note that strcmp() should be run twice, once with different strings reporting false and once with the same strings reporting true. To set the equals flag think about what operation we know will set the equals flag for us. Note that this test code is in a separate file, when we have tested our string library we can assemble it and simply link it to any program where we would like to use strings, such as further projects in this course. I will describe the test library below as an incremental build. Code Starter: /* Your template comments...*/ .global strfix .global strcat .global strcmp .global strcpy .global strlen .global strlwr .global strupr .global strim .global strprint /* Describe your subroutine, what registers it expects, what registers it returns. */ * strcat: @ your code goes here. MOV PC, LR @ return from strcat /* Describe your subroutine, what registers it * expects, what registers it returns. strcmp : @ your code goes here. MOV PC, LR @ return from strcmp @ continue to build each subroutine using this pattern. Part II: Coding your Library When you are building each of these subroutines you should make a separate code testing program which will be linked with your library to allow you to test the code in your library. Start with the code that you completed in your last lab, carefully inserting that code into your string library. Then build a separate testing program that includes a few constant null terminated strings to test your subroutines (functions) on. There are a couple of very important assembly language coding principles to pay attention to here: always start with an algorithm; build incrementally, compile and test often; test only what you are working on but always test thoroughly; and comment well. Power of the Algorithm One of the most difficult parts of assembly language programming is breaking down a problem into simple enough steps that it will translate well into machine instructions. In high level languages we have a lot of convenient functions and constructs that let us abstract the problem into bigger tasks. And often what happens with new programmers is that they begin to rely on these tools and develop an inability to problem solve things when the tools do not behave as expected. Assembly language forces you to think like a computer, which means breaking down complex tasks into very small steps. The easiest way to think this through is to make an algorithm. (For visual learners, a flow chart might be more helpful, but the advantage of an algorithm is that you can write it right into the comments to guide you in your coding work.) For example when we are working on the strcat() function in our library we can work out an algorithm and then put it into the code so that we now have a number of smaller programming challenges to solve. Think about the steps involved in appending one string to the end of another string, also map out your assumptions (these will end up in your block comments which we will see later): strcat: @ copy each byte of the first string into the @ destination string excluding the null. @ copy each byte of the second string into the @ destination string including the null. @ return user to the calling environment MOV PC, LR @return from strcat Note that the algorithm is simply statements that say what you are going to do in that section. If you have more than one sentence in assembly language programming, then you are probably trying to do too much in one step. Each statement is a separate programming challenge. Once we have an algorithm, we can complete each challenge, testing them as we go, and then remove the algorithm comments rolling them into the actual comments (or leave them if you like). Note that if you ask your lab instructor for help with a coding challenge, he or she will ask to see your algorithm. The Wise Coder Builds Incrementally and Compiles Often Because assembly language involves solving lots of small problems it is not wise to try coding everything at once hoping it simply works. The more code that is running the more problems you may have to contend with, and this leads to a lot of programmer frustration. When you are working on the strcat() function it is a good practice to compile after every small challenge is done. Even if you cannot test yet, compiling will give you helpful error messages so that you can address any syntactical issues in your code. Know that you can often create interesting ways to test your code. Practice Modular Testing, Test Thoroughly Building a testing file is an important skill. Once you have a fine-tuned string library you can simply use it whenever you are working with strings. But if you have not tested each function thoroughly then you can end up with coding headaches later as you try to debug new code only to have the offending code in a part of the library which you thought was perfectly functional. For example, in our strcat() challenge we could write testing code that prints out the destination string. If we run it after the first part is coded it should print the first part of our string and anything else until it hits a null. That is what is expected as the second string is the one that contains the null termination. Once we have tested both challenges and created a combined null-terminated string it is then time to get thorough. Test with the first string also being the destination, note what happens and then include any restrictions to safely use your subroutine in your block comments. Do the same with the second string as the destination (this will give you strange results). When you know the bounds of how you can safely use your subroutine and have worked out any bugs, it is time to complete your comments and then move onto the next subroutine. One final comment, when you have tested a subroutine you can comment out the testing code so that you are only testing the one subroutine at a time. This way you are sure that any errors that arise come from the code you are working on. This is a case where block comments are boss. Commenting Strategically The commenting strategy for any programming language is similar. In assembly there is a granularity of commenting that is not always necessary in higher level languages where a line of high-level code is almost English-like in its construction. However, no matter what language you are coding in subroutines (functions, methods, etc.) follow a definitive pattern of commenting that is strategic. For the subroutine you want to identify three things: 1. What the subroutine does. This is a short sentence or two describing exactly what the function is supposed to do. For our strcat() function the what is that it combines two strings into a single longer string. 2. What the subroutine expects before it starts. In traditional programming you would describe what parameters are sent in with the function call, but in assembly language programming the expectations are what types of values a function expects in any designated registers. For our strcat() we need at least three registers set up with addresses to strings. 3. What the subroutine will produce before it exits. In traditional programming you would describe the return value of a function, but in assembly you will describe any registers that hold values returned by the function. In our strcat() function there really is not a return value unless we decided to have a counter return the size of the new string in bytes or if we reset the address in the destination string to the start of the new string. If we do either of these things we should mention that in the comments. Here is an example of the block comment for our strcat() subroutine: strcat: * /* strcat() is a function that appends one string * to the end of another string. * This function takes a string address in ro as * the destination string. RO can be the same as r1 * provided rl has ample room to have another another string added to it. * This function also takes addresses to strings * in rl and r2 as the first and second strings * respectively. * When this function is done it simply returns * the user to the calling code. */ @ copy each byte of the first string into the @ destination string excluding the nuli. @ copy each byte of the second string into the @ destination string including the nuli. @ return user to the calling environment MOV PC, LR @ return from strcat You may want to vary your commenting to your own style, but make sure that you provide adequate commenting so that anyone can use your string library. Make sure that you complete and fully comment your library code. Include your testing code and the library code in a zip file. Upload your completed code onto BrightSpace. Read the entire lab instruction before starting. This lab is to be completed on BrightSpace any lab worksheets handed in will be discarded. Carefully follow the procedures outlined in this lab worksheet. If at any time you are unsure or are having problems, consult your lab instructor. Required Equipment: Raspberry Pi, GCC compiler, text/code editor. Part I: Building a String Library In our last lab we explored some common string functions like those found in the C library string.h. In this lab we will be exploring how we can create our own string library, a library that we can simply include whenever we know we will have to deal with string arrays. The This library will consist of the following subroutines (functions): strfix() takes a newline terminated string, such as returned by the READ syscall, and terminates it with a NULL. All of the following functions will assume a NULL terminated string. strcat() - appends one string to the end of another. strcmp() compares two strings and sets the equals flag if they are identical. strcpy() - copies a string into another memory location. strlen() returns the number of characters in a string. strlwr () - converts all alphabetic characters to lowercase. strupr() - converts all alphabetic characters to uppercase. strim() - removes whitespace padding at the beginning and end of a string. This function will take a flag value that tells the subroutine if it should remove extra spaces from the front, end, or both front and end of the string strprint() - prints out a null terminated string of any length. When you create a library, you will declare all the externally available functions as global so that the linker can correctly connect it to our main code. For this project you will create the library and another program that calls and displays strings demonstrating each of the functions. You should use some set strings for testing, no user input, and demonstrate that each subroutine works correctly in whatever order you desire). Note that strcmp() should be run twice, once with different strings reporting false and once with the same strings reporting true. To set the equals flag think about what operation we know will set the equals flag for us. Note that this test code is in a separate file, when we have tested our string library we can assemble it and simply link it to any program where we would like to use strings, such as further projects in this course. I will describe the test library below as an incremental build. Code Starter: /* Your template comments...*/ .global strfix .global strcat .global strcmp .global strcpy .global strlen .global strlwr .global strupr .global strim .global strprint /* Describe your subroutine, what registers it expects, what registers it returns. */ * strcat: @ your code goes here. MOV PC, LR @ return from strcat /* Describe your subroutine, what registers it * expects, what registers it returns. strcmp : @ your code goes here. MOV PC, LR @ return from strcmp @ continue to build each subroutine using this pattern. Part II: Coding your Library When you are building each of these subroutines you should make a separate code testing program which will be linked with your library to allow you to test the code in your library. Start with the code that you completed in your last lab, carefully inserting that code into your string library. Then build a separate testing program that includes a few constant null terminated strings to test your subroutines (functions) on. There are a couple of very important assembly language coding principles to pay attention to here: always start with an algorithm; build incrementally, compile and test often; test only what you are working on but always test thoroughly; and comment well. Power of the Algorithm One of the most difficult parts of assembly language programming is breaking down a problem into simple enough steps that it will translate well into machine instructions. In high level languages we have a lot of convenient functions and constructs that let us abstract the problem into bigger tasks. And often what happens with new programmers is that they begin to rely on these tools and develop an inability to problem solve things when the tools do not behave as expected. Assembly language forces you to think like a computer, which means breaking down complex tasks into very small steps. The easiest way to think this through is to make an algorithm. (For visual learners, a flow chart might be more helpful, but the advantage of an algorithm is that you can write it right into the comments to guide you in your coding work.) For example when we are working on the strcat() function in our library we can work out an algorithm and then put it into the code so that we now have a number of smaller programming challenges to solve. Think about the steps involved in appending one string to the end of another string, also map out your assumptions (these will end up in your block comments which we will see later): strcat: @ copy each byte of the first string into the @ destination string excluding the null. @ copy each byte of the second string into the @ destination string including the null. @ return user to the calling environment MOV PC, LR @return from strcat Note that the algorithm is simply statements that say what you are going to do in that section. If you have more than one sentence in assembly language programming, then you are probably trying to do too much in one step. Each statement is a separate programming challenge. Once we have an algorithm, we can complete each challenge, testing them as we go, and then remove the algorithm comments rolling them into the actual comments (or leave them if you like). Note that if you ask your lab instructor for help with a coding challenge, he or she will ask to see your algorithm. The Wise Coder Builds Incrementally and Compiles Often Because assembly language involves solving lots of small problems it is not wise to try coding everything at once hoping it simply works. The more code that is running the more problems you may have to contend with, and this leads to a lot of programmer frustration. When you are working on the strcat() function it is a good practice to compile after every small challenge is done. Even if you cannot test yet, compiling will give you helpful error messages so that you can address any syntactical issues in your code. Know that you can often create interesting ways to test your code. Practice Modular Testing, Test Thoroughly Building a testing file is an important skill. Once you have a fine-tuned string library you can simply use it whenever you are working with strings. But if you have not tested each function thoroughly then you can end up with coding headaches later as you try to debug new code only to have the offending code in a part of the library which you thought was perfectly functional. For example, in our strcat() challenge we could write testing code that prints out the destination string. If we run it after the first part is coded it should print the first part of our string and anything else until it hits a null. That is what is expected as the second string is the one that contains the null termination. Once we have tested both challenges and created a combined null-terminated string it is then time to get thorough. Test with the first string also being the destination, note what happens and then include any restrictions to safely use your subroutine in your block comments. Do the same with the second string as the destination (this will give you strange results). When you know the bounds of how you can safely use your subroutine and have worked out any bugs, it is time to complete your comments and then move onto the next subroutine. One final comment, when you have tested a subroutine you can comment out the testing code so that you are only testing the one subroutine at a time. This way you are sure that any errors that arise come from the code you are working on. This is a case where block comments are boss. Commenting Strategically The commenting strategy for any programming language is similar. In assembly there is a granularity of commenting that is not always necessary in higher level languages where a line of high-level code is almost English-like in its construction. However, no matter what language you are coding in subroutines (functions, methods, etc.) follow a definitive pattern of commenting that is strategic. For the subroutine you want to identify three things: 1. What the subroutine does. This is a short sentence or two describing exactly what the function is supposed to do. For our strcat() function the what is that it combines two strings into a single longer string. 2. What the subroutine expects before it starts. In traditional programming you would describe what parameters are sent in with the function call, but in assembly language programming the expectations are what types of values a function expects in any designated registers. For our strcat() we need at least three registers set up with addresses to strings. 3. What the subroutine will produce before it exits. In traditional programming you would describe the return value of a function, but in assembly you will describe any registers that hold values returned by the function. In our strcat() function there really is not a return value unless we decided to have a counter return the size of the new string in bytes or if we reset the address in the destination string to the start of the new string. If we do either of these things we should mention that in the comments. Here is an example of the block comment for our strcat() subroutine: strcat: * /* strcat() is a function that appends one string * to the end of another string. * This function takes a string address in ro as * the destination string. RO can be the same as r1 * provided rl has ample room to have another another string added to it. * This function also takes addresses to strings * in rl and r2 as the first and second strings * respectively. * When this function is done it simply returns * the user to the calling code. */ @ copy each byte of the first string into the @ destination string excluding the nuli. @ copy each byte of the second string into the @ destination string including the nuli. @ return user to the calling environment MOV PC, LR @ return from strcat You may want to vary your commenting to your own style, but make sure that you provide adequate commenting so that anyone can use your string library. Make sure that you complete and fully comment your library code. Include your testing code and the library code in a zip file. Upload your completed code onto BrightSpace

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts