summary for this article :key theme, major findings, and key implications

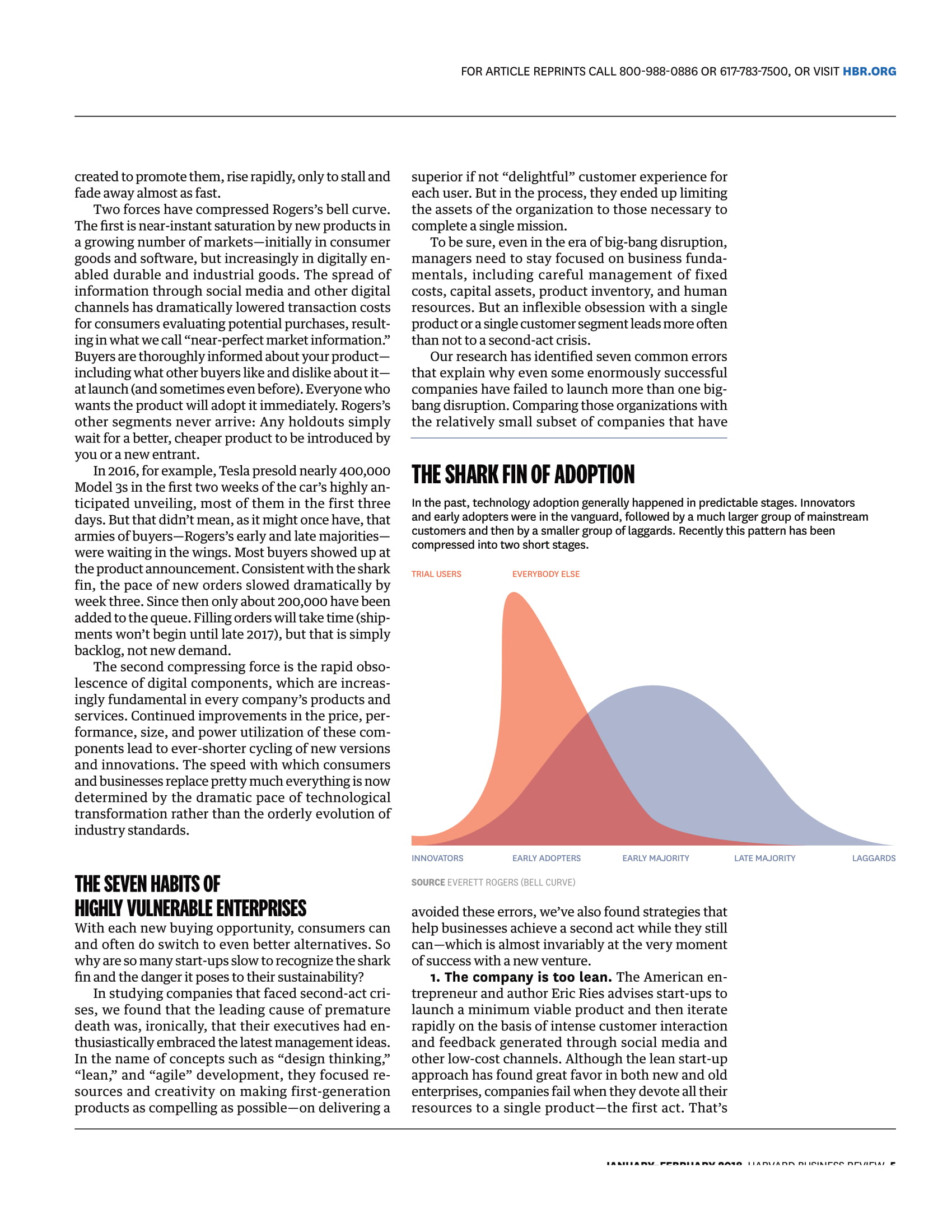

Harvard Business Review REPRINT R1801G PUBLISHED IN HBR JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018 ARTICLE INNOVATION Finding Your Company's Second Act How to survive the success of a big-bang disruption by Larry Downes and Paul NunesFEATURE FINDING YOUR COMPANY'S SECOND ACT FINDING YOUR COMPANY'S SECOND ACT How to survive the success of a big-bang disruption BY LARRY DOWNES AND PAUL NUNES ILLUSTRATION BY CHRIS BUZELLI\fFEATURE FINDING YOUR COMPANY'S SECOND ACT why do so few companies achieve successful second acts? Too often they grow incredibly quickly and then cool off almost as fast. The average life span on the sap 500 has fallen from 6'] years in the 192.05 to 15 years today. TIIE IlllSVlEll New products quickly saturate markets: sales spike early and then plummet. Digital componens rapidly make products obsolete. Following management mantras about strategic focus, executives limit their organization's assets to those necessary to complete a single mission and then struggle to nd a second successful revenue source. TIIE Sllll'lll The authors identify common attributes of companies that risk an existential crisis and argue that several tactics can avert one: abandoning hot products before they run out of steam, evolving to build platform or service offerings rather than products. and acquiring disruptive companies before the original business is upended. IN JULY 2016 A PANDEMIC BROKE OUT. Tiny monsters known as Pokmon suddenly appeared all over the world, threatening to use their fantas- tic powers to do battle in parks, on city blocks, and in homes. Fortunately, a dedicated volunteer force quickly arose to subdue them, using little-known technology embedded in smartphones to capture and domesticate the creatures. Pokemon Go was the rst big success in what will most likely be a potent run of new multiplayer smart phone games that use augmented-reality technology, which overlays digital images on real-world environ- ments. It was also what we have described as a \"big- bang disrupter,\" a new product that reigns largely un- contested for a period of success that is often shorter than one would expect from traditional market domi nators. (See \"Big-Bang Disruption,\" HER, March 2013.) In the case of Pokemon Go, that period was only a few months. In its rst week 7.5 million players down- loaded the game. At its peak, just one week later, 28.5 million played for an average of 1.25 hours a day. But 10 weeks later the game had largely run its course. Pokemon Go lost 15 million players in just a month. By the end of the summer the beasts were gone, along with about $6.7 billion in value for Nintendo, which co-owns the characters that were licensed to Niantic, the developer. Imagining that the $35 mlion of revenue from players in the rst month would con tinue, investors added $23 billion to Nintendo's market capitalization, which fell back to earth by August. A HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW JANUARVFEBRUARV 2018 Pokemon Go is hardly the only phenomenon that simply ended. Bigbang disrupters such as Fitbit, GoPro, Zenets, and TiVo scaled up incredibly quickly and then cooled off almost as fast. That's because they weren't ready with their next innovation. Companies in that situation may be caught not only with nothing to recapture shrinking revenue but also with their re- sources committed to a nowfaded product. Rapid and total collapse is often the result. This dramatic rise and even more dramatic fall reminds us of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who famously wrote, \"There are no second acts in American lives.\" Fitzgerald was referring to the stunning brevity of success in the booming movie industry of the early 20th century, but the same observation is even more applicable to many of today's hottest businesses. The good news is that the early demise of so many young enterprises makes it easier to study the un- derlying causes of modern business faure and their remedies. Using a database of more than 300 big bang disrupters across multiple industries, we have uncovered important lessons about how to achieve a successful second act. Though our focus here is on the moment of crisis for startups, failure to raise the curtain on a second act isn't a problem for bigbang disrupters alone. Even the most respected and successful companies in the world today rarely survive their first crisis, whenever it arrives. The average life span of compa- nies on the Standard 8: Poor's 500 has fallen from 67 years in the 19205 to just 15 years today. According to Richard Foster, an executive in residence at the Yale Entrepreneurial Institute, in 2020 as many as three-quarters of companies in the index will be companies that were unheard of in 2010. This shortened life cycle is primarily the result of rapidly spreading digital disruption in industries largely untouched by the rst wave of internet trans- formationincluding manufacturing (disrupted by 3-D printing and the intemet of things), agriculture (drones and sensors), transportation (autonomous vehicles), and professional services (articial intelli- gence). Even if secondact crises are most acute among start-ups, incumbents would do well to understand why they occur and how to avoid them. WHY THE SECOND-AH EXISTS Accelerating technological improvements have changed the speed with which new innovations penetrate markets. Graphed over time, the market adoption of innovations now resembles a dramatic shark na dangerously deformed version of Everett Rogers's classic bell- curve model of diffusion. (See the exhibit \"The Shark Fin of Adoption\") Rogers's ve dis tinct market segments have been reduced to two: trial users, who help develop the product, and everybody else. Disruptive products, and often the businesses FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500. OR VISIT HBR.ORG created to promote them, rise rapidly, only to stall and fade away almost as fast. Two forces have compressed Rogers's bell curve. The rst is near-instant saturation by new products in a growmg number of marketsinitially in consumer goods and software, but increasingly in digitally en- abled durable and industrial goods. The spread of information through social media and other digital channels has dramatically lowered transaction costs for consumers evaluating potential purchases, result- ing in what we call \"near-perfect market information.\" Buyers are thoroughly informed about your product including what other buyers like and dislike about it at launch (and sometimes even before). Everyone who wants the product will adopt it immediately. Rogers's other segments never arrive: Any holdouts simply wait for a better, cheaper product to be introduced by you or a new entrant. In 2016, for example, Tesla presold nearly 400,000 Model as in the rst two weeks of the car's highly an ticipated unveiling, most of them in the first three days. But that didn't mean, as it might once have, that armies of buyersRogers's early and late majorities were waiting in the wings. Most buyers showed up at the product announcement. Consistent with the shark fin, the pace of new orders slowed dramatically by week three. Since then only about 200,000 have been added to the queue. Filling orders will take time (ship- ments won't begin until late 2017), but that is simply backlog, not new demand. The second compressing force is the rapid obso lescence of digital components, which are increas ingly fundamental in every company's products and services. Continued improvements in the price, per- formance, size, and power utilization of these com- ponents lead to ever-shorter cycling of new versions and innovations. The speed with which consumers and businesses replace pretty much everything is now determined by the dramatic pace of technological transformation rather than the orderly evolution of industry standards. THE SEVEN HABITS 0F HlllV WlHERIIBlE ENTERPRISES With each new buying opportunity, consumers can and often do switch to even better alternatives. So why are so many start-ups slow to recognize the shark fin and the danger it poses to their sustainability? In studying companies that faced second-act cri- ses, we found that the leading cause of premature death was, ironically, that their executives had en- thusiastically embraced the latest management ideas. In the name of concepts such as \"design thinking,\" \"lean,\" and \"agile\" development, they focused re- sources and creativity on making first-generation products as compelling as possibleon delivering a superior if not \"delightful\" customer experience for each user. But in the process, they ended up limiting the assets of the organization to those necessary to complete a single mission. To be sure, even in the era of big-bang disruption, managers need to stay focused on business funda- mentals, including careful management of fixed costs, capital assets, product inventory, and human resources. But an inexible obsession with a single pro duct or a single customer segment leads more often than not to a second-act crisis. Our research has identied seven common errors that explain why even some enormously successful companies have failed to launch more than one big- bang disruption. Comparing those organizations with the relatively small subset of companies that have THE SHARK FIH 0F ADOPTION tn the past, technology adoption generally happened in predictable stages. Innovators and early adopters were in the vanguard, followed by a much larger group of mainstream customers and then by a smaller group of laggards. Recently this pattern has been compressed into two short stages. TRIAL USERS EVERYBODY ELSE INNOVATORS EARLY ADOPTERS EARLY MAJORITY SOURCE EVERETT ROGERS (BELL CURVE) avoided these errors, we've also found strategies that help businesses achieve a second act while they still canwhich is almost invariably at the very moment of success with a new venture. 1. The company is too lean. The American en- trepreneur and author Eric Ries advises start-ups to launch a minimum viable product and then iterate rapidly on the basis of intense customer interaction and feedback generated through social media and other lowcost channels. Although the lean startup approach has found great favor in both new and old enterprises, companies fail when they devote all their resources to a single productthe first act. That's LATE MAJORITY LAGGARDS IAIIII-nvnl-Ennllnnv nun-n Ilnnllnnn rIIInuII-n nrmnu r FEATURE FINDING YOUR COMPANY'S SECOND ACT because market saturation occurs faster all the time, resulting in the rapid downward slope of the shark n. Some companies tragically mistake that decline for a failure to satisfy users, triggering what Ries calls a \"pivot\"a \"structured course correction\" in product design. But if the market has simply moved on and is waiting for the next innovation, pivoting isn't going to help. Management must organize a new team to begin the cycle from scratch before saturation. Otherwise the company will enter a death spiral, trying to serve the incremental needs of a dwindling number of once enthusiastic customers and surviving, if at all, by be- ing acquired by a more diversied company, often at a re-sale price. Consider the lean methodology acolyte Groupon, which continues to pivot around its core innovation only to fade quickly over the next few months as the company belatedly scrambled for a replacement. 2. The company's capital structure is built to fail. One area where lean can still be good is corpo- rate nance. Private companies and startups boot strapped with funding from the founders or their friends and family have the most exibility to shift strategy and resources to the next product when the time comeseven if that time is sooner than anyone would like. Angel and venture capital investors, so- called \"smart money,\" likewise appreciate the dangers of overreliance on a single product and often nudge management toward a second act. But the trend of sudden market saturation encour- ages companies to raise substantial outside capital for production and expansion much earlier in the process COMPANIES FAIL WHEN THEY DEVOTE All THEIR RESOURCES T0 II SINGLE PRODUCT-THE FIRST ACT. of \"social shopping,\" whereby consumers leverage scale to negotiate discounts from merchants. Despite strong indications that enthusiasm for social shopping was eeting, Groupon remained singularly focus ed on proving the concept, methodically tweaking its inter- face, acquiring its failing competitor LivingSocial, and halfheartedly expanding group buying into travel. Meanwhile, inattention to basics has led to ballooning operating expenses and run-ins with the SEC over em- barrassing accounting errors both before and after its 2011 1P0; since then the company has lost nearly 90% of its value. It isn't just strict adherents of the lean philosophy that risk missing the market forest owing to an obses- sion with customer trees. Makers of smartphone soft- ware apps, which have a rapid life-and-death cycle, frequently become anchored to product development that focuses on solving the wrong problem. Zynga, the wildly successful game developer of FarmVille and other hits, barely survived the shark n of its social drawing and guessing game Draw Something, which jumped to 16 million players in a matter of weeks, 6 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018 than was once the case. Startups may feel forced to turn to crowdfunders or other investors who offer little value beyond money. 0r, worse, they may take on non- equity debt. A deeply leveraged capital structure works only during times of extraordinary growth. Ifrnarkets contract even modestly, traditional creditors quickly become anxious, encouraging or even forcing re trenchment at the precise moment when investment in innovation is critical to survival and future expansion. One-act companies also take on other long-term encumbrances before they need to, limiting future exibility. Although start-ups generally don't have union contracts, pension commitments, or other trap pings that may hold back older companies, they fre- quently do have excessive operating expenses, such as catered lunches, generous leave policies, free day care, and leased ofce space in high-end properties. These costs are just as dangerous, especially when markets change suddenly. 3. The company has lost its head. In the typ- ical Silicon Valley pattern, venture investors give visionary entrepreneurs considerable freedom to FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500, OR VISIT HER.ORG JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW 7FEATURE FINDING YOUR COMPANY'S SECOND ACT run their organizations, often haphazardly, until product launch. But once the company has garnered real customers, investors quickly push for experi- enced managementor \"adult supervision\"to take over day-to-day operations. (See \"When Founders Go Too Far," by Steve Blank, HBR, NovemberDecember 2017.) Yahoo's Jerry Yang and Twitter's Evan Williams, for instance, ended up in engineering roles that were too constraining. Without the means or the encour- agement to continue innovating, founders soon quit, often to launch other start-ups, taking their most trusted colleagues along with them. Investors in a startup frequently fund the found er's next venture, so for them the departure of the visionary may mean little more than a change of ad- dress. But for the company left behind, the second-act problem becomes acute. Experienced managers focus on improving the original product, which is often the target of sudden competition from new entrants with ready access to the same component technologies and no commitment to a business model that may have outlived its usefulness. In response, the company doubles down on its existing strategy, increasing its chances of being stranded when the market moves on. Google's inves tors saw the risk in time and brought the founders back into leadership roles before the company had become reliant on unsustainable growth in search advertising. Apple famously rehired Steve Jobs for a second and even more glorious incarnation of the company after his seasoned replacement failed to launch new products that consumers wanted. Yahoo, meanwhile, stumbled through a succession of CEOs poorly tted for the task of reinventing the company, leading investors to look for an exit. 4. The company is overserving investors. Public investors and the research analysts who advise them can be even more conservative than creditors. Beloved start-ups that cash in on IPOs nd themselves stymied by investors who say they want more disrup- tion but pummel the company's stock price and man- agement when profits don't show up fast enough. Second acts are postponed as managers respond to investors' demands. Management teams at companies including Snap and Blue Apron, for example, are already struggling to balance a dynamic strategy with the demands of the public market after recent and possibly prema ture IPOs. And although many factors contributed to the diiculties of the business networking disrupter Linkedln, which went public in 2011, the company's repeated failure to generate the kind of revenue that Wall Street expected led to a collapse of its stock price five years later. That made LinkedIn an attractive takeover target for Microsoft, which believed it could restore LinkedIn's lost lusterbut at the cost of the company's independence. ll HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW' JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018 Adjusting strategy to appease shareholders can quickly threaten the very mission of a young business, to everyone's disappointment. When the handmade goods pioneer Etsy went public, in 2015, CEO Chad Dickerson limited retail investors to a $2,500 stake, hoping to ensure that the company's social and politi- cal missions would continue to take priority. But after two years of ballooning costs and confusion among Etsy's artisanal sellers over a tortured decision to al- low manufactured goods on the site, activist investors forced Dickerson out, along with 8% of Etsy's staff. The company may now lose its status as a socially conscious B corporation, and a promised restructuring as a public-benet corporation is unlikely. Instead of helping Etsy burnish its brand, the company's public investors may wind up killing its soul. 5. The company won the lottery. In an era when new products and services are quickly built from com- binations of interchangeable hardware and software parts, a growing number of big-bang disrupters have achieved private and sometimes public valuations in the billions of dollars in record time. These \"unicorn" prices seem based not on any investing fundamentals but simply on earlyuser fervor and the promise of revenues to followthe result of nearperfect market information generating winner-takeall success. Some of today's most admired start-ups simply got luckya fact that becomes clear when a company fails utterly to build on its initial popularity. Launching a rst product that turns out to be a bigbang disrupter can leave managers feeling invincible. Too often an ex post facto history is written that makes the enterprise's successful but accidental rst act appear to be the re- sult of exceptional management decision makinga dangerous delusion. Success frequentlybreeds failure. Twitter, which ended its rst day of public trading with a value of $24 billion, has since struggled to nd revenue and maintain explosive growth. New features, including promoted tweets, polls, streaming videos, and long-form posts, annoyed many longtime us- ers, who complained via the company's own service. Management, meanwhile, has become a revolving door. In addition to losing half its value, the company has lost its way, calling into doubt whether it ever had one. Founders who confuse a high valuation with busi- ness genius may also cripple an elegant product de- sign with all the bells and whistles wisely left out of the initial offering, alienating the devoted early customers who launched them into the spotlight in the rst place. Just months after winning Best of the Best at the 2014 Consumer Electronics Show with a virtual -reality head- set that was still a prototype, Oculus was acquired by Facebook for $2 billion. But design excesses delayed the company's rst commercial product until 2016, and the resulting price of $800 for a fully congured unit depressed consumer enthusiasm. Simpler products developed in the interim by HTC, Sony, and Samsung FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500, OR VISIT HER.ORG vastly outsold the too-much-anticipated Oculus Rift in 7. The company anticipates customers who its first year, leaving Oculus with just 4% of total sales. don't exist. In a winner-take-all phenomenon, cus- 6. The company is held captive by regulators. tomers for the big-bang disruption show up all at In response to the rapid uptake of products in the big- once, sending confusing signals about future sales and bang phase of the shark fin, stunned incumbents in the market's appetite for follow-on products. As the creasingly turn to regulators, hoping to buy time by de- Tesla example reveals, consumers use social media railing insurgents. In industries as different as aviation (threatened by drones), hospitality (Airbnb), health electronic channels to signal when a new product is a must-have, leading to a sudden rush fol- care (genetic testing), and financial services (bitcoin), incumbents first lobby for an outright ban on the dis- lowed by a trickle. Everett Rogers's gentle bell curve of rupters. When consumers revolt, regulators fall back on diffusion disappears, leaving only the shark fin. hastily crafted and often crippling new rules, designed Consider the smartwatch, effectively a wearable smartphone. Apple garnered one million preorders LAUNCHING A FIRST PRODUCT THAT TURNS OUT TO BE A BIG BANG DISRUPTER CAN LEAVE MANAGERS FEELING INVINCIBLE. with little or no understanding of how the start-ups' from U.S. customers on the first day of availability for products or services differ from those of incumbents. the Apple Watch, at a relatively high price point. But In response, start-ups must now engage legal smartwatches don't seem to have a second act based counsel much sooner than was ever before thought on new features, new looks, or new hardware, let necessary, diverting scarce resources from building alone the rapid replacement cycle of smartphones and the company to dealing with city councils, public util- tablets. Sales have been essentially flat, leading some ity commissions, and legislative hearings. Around the analysts to suggest that consumers have rejected world, Uber, Airbnb, and other sharing-economy en smartwatches in favor of fitness-oriented products terprises are engaged in pitched battles for the right with similar features. to do business at all, much less to do it without taking Anticipating more customers and new market seg- on the regulatory legacy of incumbent transportation ments, managers conditioned to the bell curve commit companies and hotels. costly resources to expanded production and distri- For start-ups desperate to stay in business, this trend carries hidden risk: They can quickly develop bution for follow-on sales that never come. Or, worse, they produce vast inventories that quickly become un- the same dependency on regulators that stalls in- sellable at any price. The game developer THQ, which bents. Having legal advisers makes them newly experienced great success with a drawing tablet for the cautious. They, too, come to believe that they can use Nintendo Wii, exuberantly committed to other game the law as a barrier against next-generation innova tors. They may win the regulatory battle, but in do- platforms in 2010. But the launch of the Apple iPad ing so they lose their momentum and, eventually, the soon after suddenly shifted the market to stand-alone drawing applications. THQ continued to manufacture once-potent sympathies of their customers. its tablets anyway, warehousing 1.4 million unsold IANITADV-CEDDIIADV 2010 WADW/ADD DI ICIMECC DEVIEW/ QFEATURE FINDING YOUR COMPANY'S SECOND ACT units. The company was forced into bankruptcy and never recovered. THQ's president later confessed, \"I'm not sure how that happened.\" SURVIVING TO A SECOND ACT Just avoiding the pitfalls described above is not enough to separate the standouts from the bumouts. Timing the shift from one shark fin to the next is equally critical. In the era of big-bang disruption, the life-or-death moment for any enterprise comes well before sudden declinewhen a fast-growing market abruptly shifts course. with, redirecting as many of their best assets as they can while still generating revenue to nance the shift. After dispatching Blockbuster with its original DVD mail-delivery service, for example, Netix famously launched intemet-based movie delivery in 2007, long before broadband speed or penetration was ready for it. The company was accused of cannibalizing its own revenue, but CEO Reed Hastings understood that DVD delivery was only an interim solution and an inefcient one at that. Today the company has lever- aged its streaming dominance into the production of original content. It now has more than twice as many subscribers as the cable giant Comcast. MOST SECOND-ACT SURVIVORS IAIINCH NOT A SINGLE PRODUCT BUT, RATHER, AN ECOSYSTEM. The few companies that survive to a second act and become truly sustainable enterprises are those that see the big bang for what it isa short burst of success, followed by everbriefer windows of oppor- tunity. Companies that go on to launch a second prod uct, enter a second market, or lead a second technical revolution do so because their founders structured them not as one-offs to solve a specic problem but as engines of innovation that spawn a thousand exper- iments. Those founders also have the wisdom to see which experiments are promising and which need to be terminated quickly and (relatively) painlessly. To ensure that your business is a second-act survivor, learn from some of these tactics of perennial disrupters: Abandon the successful product before it runs out of steam. Second-act companies not only see the top of the big-bang tsunami coming but also have the courage to jump from one shark n to another before they've extracted the last drops of value. While many companies get caught in the eddy of the wave, serving a dwindling number of legacy customers who haven't moved to the better and cheaper alternative, the sur- vivors go in search of new technology to experiment 10 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018 Build a platform, not a product. Most second-act survivors launch not a single product but, rather, an ecosystem, connecting customers, suppliers, and oth- ers and deriving revenue from services provided to all of them, including payment processing, curation, dis pute resolution, data analysis, and quality assurance. As tastes change, the platform abides. Internet giantsincluding Google, Amazon, Facebook, and China's Tencent Holdingshave honed this lesson to razor sharpness. Tencent, for example, leveraged its gaming platform and exper tise in smart devices to add the WeChat messaging app, now a daily obsession for more than a billion Chinese. WeChat, which has itself expanded to in- clude social-networking tools and mobile payments, has revenue of close to $2 billion annually, most of it still related to online gaming. The platform strategy is now being imitated by sharing-economy enterprises such as Uber, Airbnb, and TaskRabbit (recently acquired by IKEA). These network-based companies have no physical assets of their own; they simply connect buyers and sell ers while relentlessly driving down the transaction costs that make their markets inefcient. That leaves FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500. OR VISIT HBRDRG the companies with considerable exibility to add services, change interfaces, and redesign backend relationships with the actual suppliers as market needs rapidly evolve, greatly reducing second-act risk. Turn your initial product into a service. The real value in a disruption may be the infrastructure that was built to make, deliver, and support it. Unless the company's product is a cobbledtogether throwaway, as is true for many software start-ups, a second act may lie in leasing core tools and processes to others, perhaps in very different businesses and industries. Since 2015, for example, the fitness technology leader Under Armour has invested heavily in the na- scent internet of things, launching its own line of t ness trackers developed in partnership with HTC. But Under Armour has generated stronger reviews for its Connected Fitness platform, which allows customers to import tracking data from a wide range of sources and thirdparty products, including those of Under Armour's competitors, into a single dashboard and a series of apps. A partnership with Johns Hopkins Medicine adds research-based health guidance for the 200 million members of Under Armour's Connected Fitness community. 0r consider Amazon, which started 011.\" as an on line retailer selling rst books and then pretty much everything. From there it was a relatively short leap to hosting other retailers. Now the company offers cloud computing to any organization or individual through Amazon Web Servicesthe fastest-growing IT busi- ness in history. AWS hosts operational software, data, and processing for millions of other enterprises, mak ing it the dominant provider. In2016 it generated more than $3 billion in operating incomealmost triple that of the company's retail divisions. The need to develop services from a one-shot product is a lesson being learned the hard way by the sportscamera superstar GoPro, which has suffered slowing revenue and a catastrophic drop in its stock price (a decline of 90% in just a few years). The com- pany prematurely reached saturation in its hardware business amid the rapid improvement of high-end cameras embedded in smartphones. Despite painful sta" cuts, the company has spent heavily both inter nally and on acquisitions to build new software for state-of-the-art video-editing tools that can be used regardless of the original source of a recording. The company's new strategy, CEO Nick Woodman said recently, is to become a trusted neutral video host: \"the Switzerland of content creation.\" Invest in or acquire nascent disrupters. Companies with a successful rst act may nd them- selves flush with cash and relatively cheap nancing from venture investors. That money, if spent early, can fuel a second act. Even as the company contin ues serving customers of a popular product, it can invest in or acquire outright the next generation of disrupters. Evolving through acquisition has been a preferred strategy in Silicon Valley all along, notably for compa nies such as Cisco, Oracle, and Qualcomrn. But even relatively young companies have taken a page from their playbook and expanded on it. Although the multibillion-dollar price tags for recent early-stage ac- quisitionsincluding Facebook's $19 billion purchase of the messaging service WhatsApp and Google's $3 billion buy of the internetofthings pioneer Nest may leave many scratching their heads, for second-act companies these are just a hedge against an uncertain rture, well worth the price. lllIIllli TO FIGHT ANOTHHl DAY The sooner a successful startup accepts the reality that its big-bang disruption may have resulted more from great timing than from uncanny foresight, the better its chances of resisting the bad habits that sank so many of the companies in our study. But that's only the rst step toward a sustainable new enterprise. Even as consumers enthusiastically engage with a rst-act product, managers must pre- pare for its inevitable collapse, shifting their focus to the creation of a solid platform built on business fun damentals. Secondact leaders are those who resist the temptation to take on unnecessary capital and op erational obligations and instead invest in a product architecture that can be reshaped however and when- ever the market dictates. The rewards for such virtuous behavior are pro found. Companies that survive an early secondact crisis become innovation incubators, focused not on a single product or even a single market but on a corporate culture that attracts the best engineering and marketing talent, along with stakeholders who encourage longterm investments in repeatable dis ruption. In short, they develop brands worthy of their stratospheric valuations. Today such enterprises are few and far between. Most are found in the pressure cooker of the intemet ecosystem, where survival instincts are of neces- sity the most valuable entrepreneurial trait. But for every successful secondact enterprise, a hundred once-promising disrupters simply disappear. And as we've said, it's not just start-ups that quickly face an existential crisis. As the shark fin becomes a re- ality in every industry, incumbent businesses likewise may nd themselves suddenly in need of a secondact strategyespecially those whose most recent bit has already enjoyed an extended run. 6 HER Reprint meme El mm Mill is a senior fellow with Accenture Research and a coauthor of Unleashing the Killer App. Pllll llllllES is the global managing director of thought leadership at Accenture Research and a coauthor of Jumping the swcurve. They are the authors of Big Bang Disruption: Strategy in the Age of Devastating Innovation (Portfolio. 2014). JANUARVFEBRLIARV 2018 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIFW' 'I'I